The Dust Bowl devastated the Great Plains in the 1930s, destroying millions of acres of crops, killing livestock, and forcing farmers to abandon their land and migrate west to find work.

Public DomainA dust storm, known as a “black blizzard,” rolls through Stratford, Texas, in 1935.

In the 1930s, the area of land known as the Great Plains — a lush flatland spanning parts of 10 states — came to be known by a different name entirely: the “dust bowl.”

One of the most severe environmental catastrophes in American history, the Dust Bowl period saw the Great Plains ravaged by droughts and dust storms that devastated the region and caused significant economic and ecological damage. For nearly a decade, the Great Plains became a virtually uninhabitable wasteland. This disaster was brought about by a mixture of farming practices that robbed the plains of their grassland in the 1920s and several major droughts in the 1930s.

As a result, some 2.5 million people abandoned their homes and migrated across the country in search of greener pastures. Although President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration implemented a series of programs to revitalize the region and ensure such a tragedy would not happen again, this decade-long period left a permanent mark on American history.

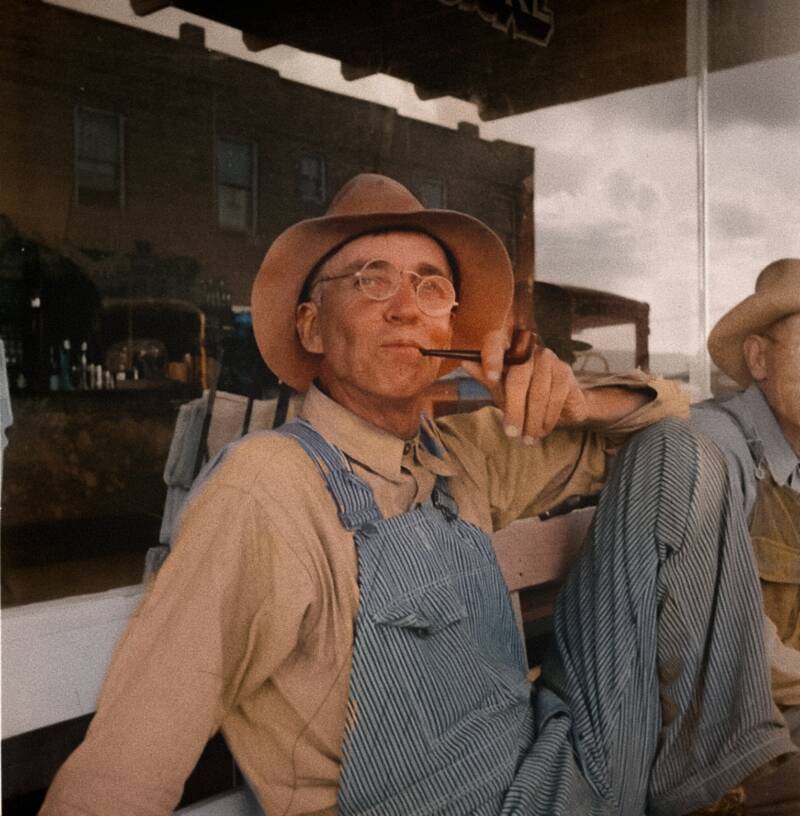

See our gallery of 44 colorized images from the Dust Bowl below to gain better insight into this tumultuous time:

What Caused The Dust Bowl?

While it would be unfair to place the blame entirely on farmers in the 1920s, they certainly played a large role in creating the Dust Bowl.

In the decades leading up to the 1930s, there was a significant agricultural expansion across the Great Plains, driven largely by low crop prices and technological advancements in farming equipment that was expensive to maintain. In order to turn a profit and pay for their machinery, farmers had to plant more — and many of them expanded their fields into submarginal land, tearing up native grasslands to do so.

However, because the semi-arid region received little rainfall, the grasses were one of the few consistent sources of water for the soil. The widespread plowing disrupted these deep-rooted grasses, which had been anchoring the dirt, and left the earth exposed and vulnerable to wind erosion. In addition, farmers often didn't practice soil conservation techniques, such as crop rotation or leaving fields fallow. This led to the depletion of nutrients in the soil, further weakening its integrity.

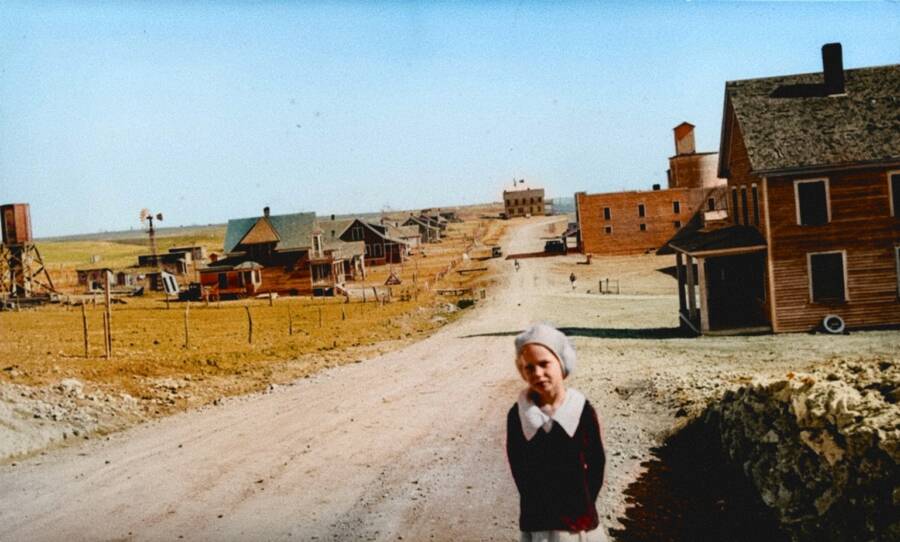

Farm Security Administration via New York Public LibraryAn all but abandoned Dust Bowl town in Mills, New Mexico, in 1935.

Government policies also impacted this environmental disaster. The Homestead Act of 1862 provided settlers with land and promoted agricultural development — but it led to farming in areas that were not necessarily suitable for it, too.

Then, in the 1930s, a series of severe droughts swept across the Great Plains, drying out the soil. When the wind blew, the loose dirt blew with it, eroding the land and creating dust storms that destroyed the region.

How The Dust Bowl Impacted People Living In The Great Plains

Library of CongressA farmer's son coughing from the dust in the air in Cimarron County, Oklahoma. 1936.

As if drought and poor harvests weren't devastating enough for Great Plains inhabitants, they soon found themselves victims of so-called "black blizzards," massive dust storms that swept across the region. These tempests reduced visibility to mere feet and covered homes, machinery, and crops in layers of dust. The "black blizzards" destroyed livelihoods and exacerbated the issues people were facing. They also introduced new complications like "dust pneumonia" that led to hundreds, if not thousands, of deaths.

Lawrence Svobida, a Kansas wheat farmer, described one of these storms in his memoir, Farming the Dust Bowl. As reported by PBS, Svobida recalled, "Birds fly in terror before the storm, and only those that are strong of wing may escape. The smaller birds fly until they are exhausted, then fall to the ground, to share the fate of the thousands of jack rabbits which perish from suffocation."

The economic impact on the region was similarly profound. The Dust Bowl only compounded the hardships many were facing due to the Great Depression, and with crops failing and livestock dying, farmers were facing financial ruin. Unable to repay their debts or sustain operations, many were forced to abandon their land.

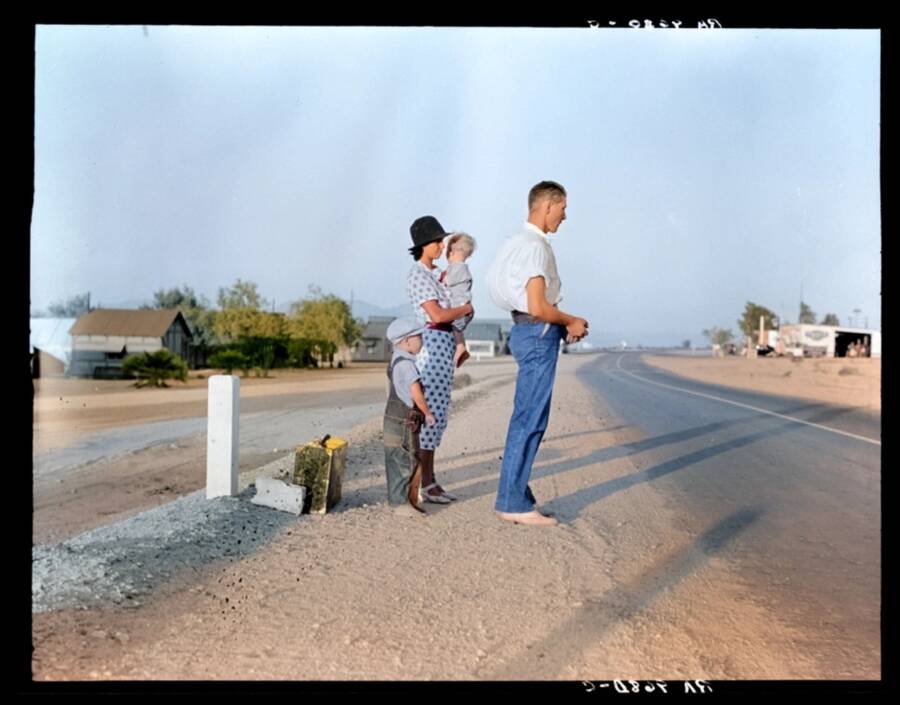

It's estimated that roughly 2.5 million people fled the affected areas between the 1930s and early 1940s, marking one of the largest mass migrations in U.S. history. These displaced people — called "Okies," regardless of where they originally came from — mostly migrated to California in search of employment and better living conditions.

There, they found frequent discrimination, poor living conditions, and limited job opportunities. It was hardly the better life they had hoped for.

Finally, by the mid-1930s, it was clear that something had to be done about the Dust Bowl at a governmental level.

How The New Deal Helped Fix The Dust Bowl — And Prevented It From Happening Again

Library of CongressThis "Okie" family was forced to leave their Oklahoma farm due to drought in 1936, and they made it to California by stopping to pick cotton along the way to pay for their travels. Here, they're seen walking to their final destination of Bakersfield after their car broke down.

In response to the crisis, the federal government, under President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal, implemented a series of initiatives and policy changes to mitigate the effects of the Dust Bowl and prevent future catastrophes of a similar nature.

One of the first major implementations was the establishment of the Soil Conservation Service in 1935. The agency was tasked with promoting sustainable farming practices to prevent soil erosion, which included educating farmers on contour plowing, crop rotation, and planting cover crops to protect the soil during the off-season.

The government also introduced the Prairie States Forestry Project to plant extensive windbreaks across the Great Plains. Between 1934 and 1942, approximately 220 million trees were planted in a line that ran from Canada to Texas with the aim of reducing wind velocity and minimizing soil erosion as a result, therefore protecting crops.

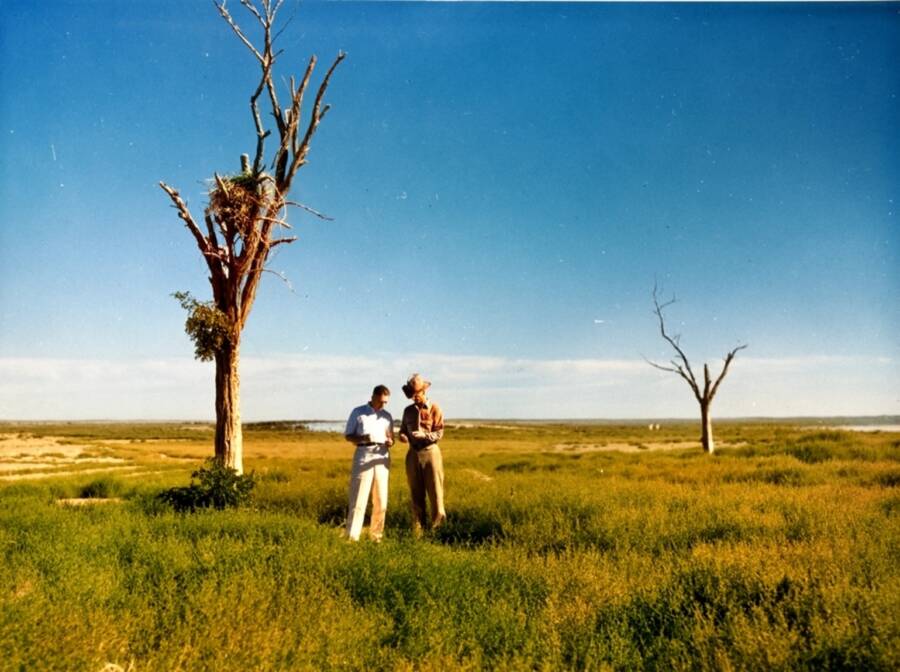

Farm Security Administration via New York Public LibraryDr. Rexford Tugwell, an American economist who helped develop President Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal, speaks with a farmer in the Texas Panhandle. 1936.

The Resettlement Administration — which later became the Farm Security Administration (FSA) — was established to assist displaced farmers. The agency provided financial aid, helped families relocate to more viable lands, and promoted cooperative farming endeavors. The FSA was also responsible for many of the photographs documenting the era, which both highlighted the plight of those affected and helped garner support for relief efforts. The Agricultural Adjustment Act also offered incentives for reducing crop acreage and provided subsidies to farmers who adopted soil conservation practices.

These combined efforts managed to accomplish their goal. By the early 1940s, soil erosion had significantly decreased, and agricultural productivity started to rebound. In addition, the droughts diminished, and the economic boom that came along with World War II helped Great Plains farmers reestablish their livelihoods.

However, the photos taken during that troubled time serve as a brutal reminder of the struggles that so many Americans faced, even nearly a century later.

After this deep dive into the Dust Bowl, learn more about the Great Depression through our gallery of 55 heartbreaking photos. Then, read all about Hoovervilles, the Depression-era shanty towns that dotted the nation.