"I do wonder if it has something to do with rebirth, and if these children could have been important symbols of that."

Sara Juengst/University of North Carolina CharlotteThe excavation was a collaborative effort between the Salango community and the research team.

Archaeologists at an Ecuadorian historical site have revealed that two individuals they unearthed were infants that had “helmets” made from the skulls of other children wrapped around their heads.

According to Forbes, archaeologists excavated the ancient Salango ritual complex on Ecuador’s central coast from 2014 to 2016. The two-year dig not only yielded human remains from 11 individuals, but also shells, artifacts, and stone figurines honoring ancestors.

The research team responsible includes Sara Juengst and Abigail Bythell of the University of North Carolina at Charlotte and Richard Lunniss and Juan José Ortiz Aguilu of the Universidad Técnica de Manabí in Ecuador. Their research has been published in the Latin American Antiquity journal.

The historical site itself dates back to around 100 B.C. and was likely used by the Guangala culture as a funerary platform. While the discoveries made in Salango as a whole are astounding, it is the atypical burial ritual of modified “helmets” that has been most intriguing for experts.

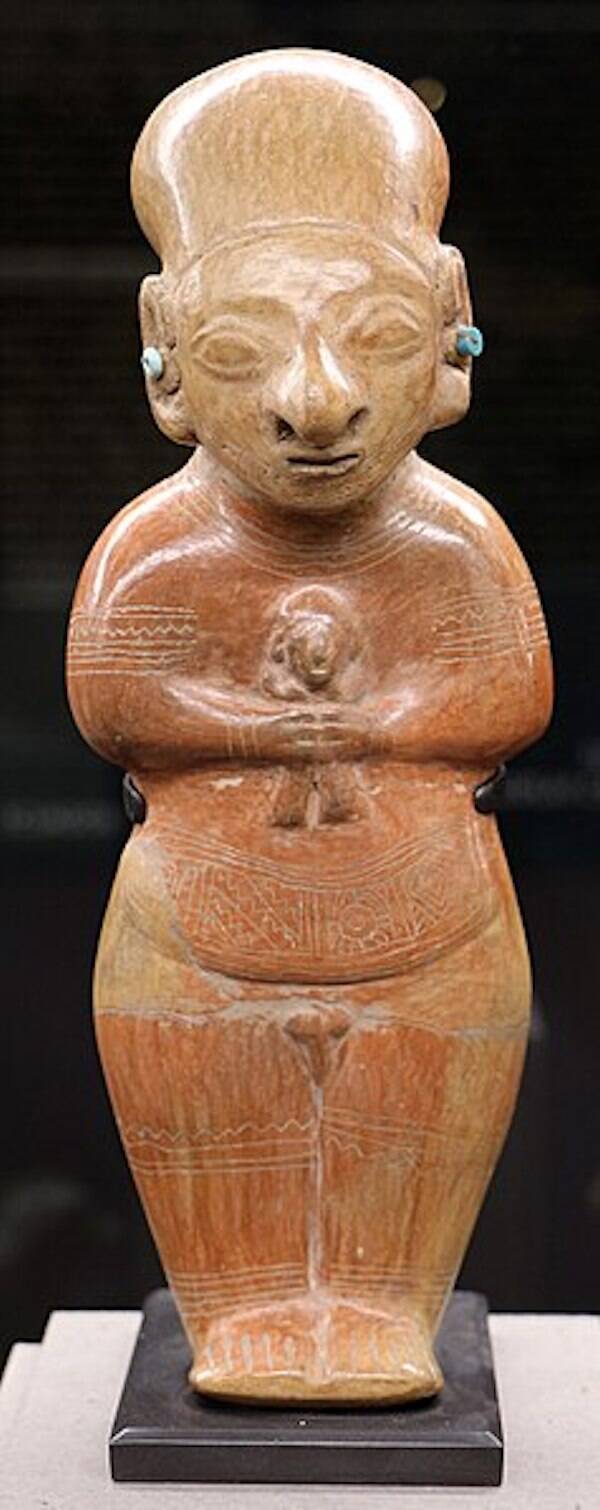

Wikimedia CommonsA traditional ancestor figurine of the coastal Guangala culture, which spanned from around 100 B.C. to 800 B.C.

One of the infants in question was around 18 months old when they died.

For some unknown reason, “the modified cranium of a second juvenile was placed in a helmet-like fashion around the head of the first, such that the primary individual’s face looked through and out of the cranial vault of the second,” the researchers explained.

The skull helmet came from a separate child, aged between four and 12 years old when they died. The second infant found with such an apparatus around their head was only between six and nine months old at death, and had a skull made from a child aged between two and 12 when they died.

According to Live Science, the helmets tightly placed over their heads likely still had flesh on them. Without this natural adhesive of sorts, it’s unlikely the helmets would’ve stuck together.

Isolated skulls are not uncommon, in terms of ancient South American mortuary scenes — though these are usually those of adults, not children. The primary motivation for this was typically the stern idolatry of ancestors, or of those who died honorably in war.

As such, finding children buried with the skulls of other children protecting their heads was a shock. Juengst and her peers have since theorized that this “may represent an attempt to ensure the protection of these ‘pre-social and wild’ souls,” with the figurines further protecting these youths.

Sara Juengst/University of North Carolina CharlotteExperts are conducting tests to find out if the infants were related to those whose skulls were used for the helmets.

“We’re still pretty shocked by the find,” Juengst said. “Not only is it unprecedented, there are still so many questions.”

One of these unanswered questions revolves around a type of bone called a “hand phalanx” found stuck between one of the infant’s heads and the helmet. Nobody knows why the bone was placed there, or whom it belonged to. The next steps in finding out are DNA and strontium isotope tests.

The overarching mystery remains what, exactly, this burial ritual as a whole intended to yield. Previous studies indicate there was a large volcanic eruption in the area that covered the region in ash — not long before these two infants were buried.

It’s speculated that this event drastically affected local food production, with these latest remains confirming there was severe malnutrition at the time of death.

Thus, the archaeologists posit, it’s possible that “the treatment of the two infants was part of a larger, complex ritual response to environmental consequences of the eruption.” Of course, more evidence is needed to confirm this.

Juengst also speculated these skulls may have been “worn in life as well as in death, so we definitely have a lot of ideas to work with.”

Sara Juengst/University of North Carolina CharlotteThe lesions in quadrants A and D suggest physical distress. Quadrants B and C show one of the skull helmets.

As it stands, a bounty of human remains and cultural artifacts has been unearthed, with thorough scientific analysis underway to learn more. For bio-archaeologist Sara Becker of the University of California Riverside, the discovery of this unprecedented burial ritual is “pretty amazing.”

“I’ve never heard of anything like it elsewhere in the Andes,” she said, and it’s made her “consider practices elsewhere where heads are buried in chests as if they are ‘seeds’ to help with agricultural productivity.”

“I do wonder if it has something to do with rebirth, and if these children could have been important symbols of that.”

Ultimately, though the sight of human remains — particularly those of children — can understandably be a troubling moment, Juengst took some interesting comfort in the details that surrounded this find.

“Dealing with the death of young infants is always emotional,” she said, “But in this case, it was strangely comforting that those who buried them took extra time and care to do it in a special place, perhaps accompanied by special people, in order to honor them.”

After learning about these ancient Ecuadorian infants, read about the massive child sacrifice site found in Peru. Then, learn about the Incan child sacrifice involving lightning.