After 200 miles aboard a train owned by their master and a nail-biting boat ride, Ellen and William Craft made their way to Philadelphia to become free.

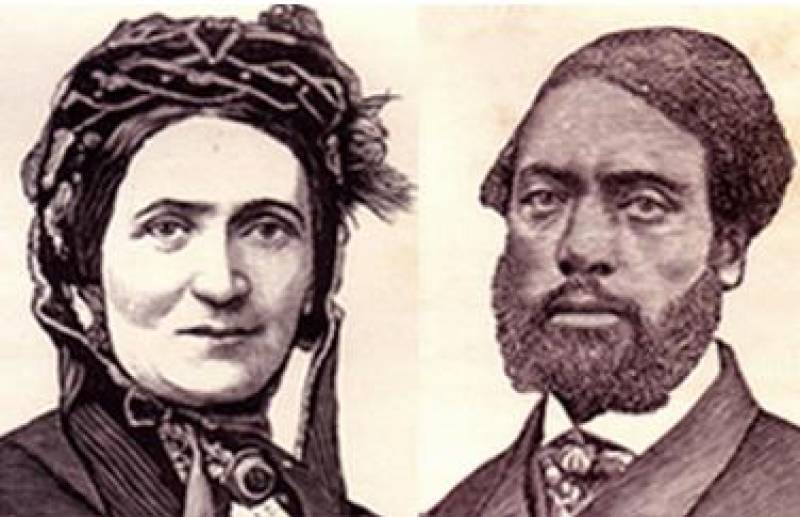

Wikimedia CommonsMarried slaves Ellen and William Craft escaped rewrote their fate embarking on an ingenius escape plan to the North.

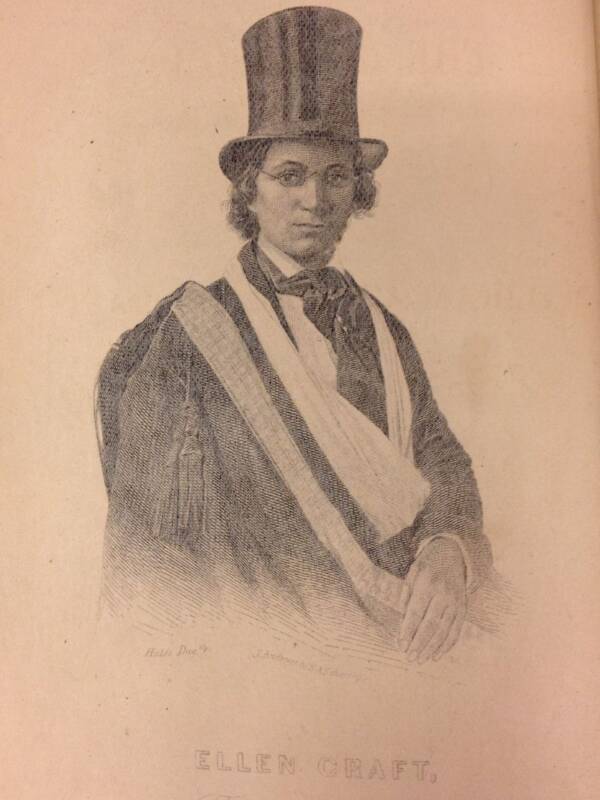

Perhaps the most daring and ingenious escape from slavery was the brainchild of enslaved married couple, Ellen and William Craft, whose story is one of danger, intrigue, and cross-dressing. Ellen Craft, the fairer-skinned of the two, posed as a white man traveling with his servant, and the two managed to run away in broad daylight by boat and train to their freedom. They even traveled first class and stayed in fancy hotels as they deceived their way to the North.

Indeed, the escape of the Crafts lives on today as one of the most imaginative plots to ever come out of the Antebellum South. So how did this daring and creative couple come to do it in the first place?

Ellen And William Craft In Slavery

Ellen and William Craft were married slaves born in Georgia during the first half of the 19th century but belonged at first to separate families.

Ellen Craft was the child of a slave owner and his biracial slave. Born in Clinton, Georgia, in 1826, Ellen’s light skin would later serve as the crux of her husband’s escape plot. According to a Smithsonian article, Ellen Craft’s complexion often caused her to be mistaken as a legitimate born child of her father’s family. This mistake bothered her master’s wife, who decided to gift Ellen Craft to her daughter, Eliza, as a wedding present in 1837.

Eliza later married Dr. Robert Collins, a respected doctor, and railroad investor. The pair made a lavish home in Macon, Georgia, which was a railroad hub at the time. Ellen served as a lady’s maid within the household. In the memoir she wrote with William Craft, Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom, Ellen and William Craft recall that Eliza was kind enough and that Ellen even received a room in their house. A comfortable cage is still a cage, however.

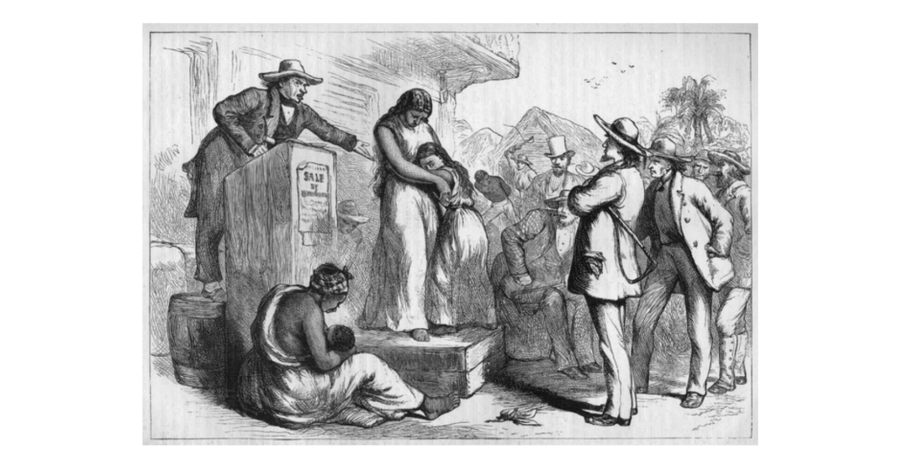

William Craft was forced to endure an entirely different upbringing. Throughout his childhood, William Craft’s masters regularly ripped his family apart by selling his parents and siblings. One master once sold William and his sister to separate slave owners. In their book, William recalled, “My old master had the reputation of being a very humane and Christian man, but he thought nothing of selling my poor old father, and dear aged mother, at separate times, to different persons, to be dragged off never to behold each other again, till summoned to appear before the great tribunal of heaven.”

William was purchased by a wealthy banker and trained as a carpenter. He was skilled, but his master claimed most of his wages. Even so, William was able to save money that would prove to come in handy. Besides, this work was also what eventually brought William to meet Ellen. Denied the opportunity to marry, the couple instead decided to “jump the broom,” which was an African ceremony that consecrated the couple’s commitment to one another in secrecy.

But the fear of being separated from their families was debilitating to Ellen and William Craft. Speaking of Ellen’s concern, William wrote, “The mere thought filled her soul with horror.” As such, though the couple eventually married one another, they initially chose not to have children out of fear of being torn apart. The Craft’s were considered “Favorite slaves” of their masters, however, and William admitted that “our condition as slaves was not by any means the worst.”

The couple still could not bring themselves to bear children in their condition. “The mere idea that we were held as chattels, and deprived of all legal rights — the thought that we had to give up our hard earnings to a tyrant, to enable him to live in idleness and luxury — the thought that we could not call the bones and sinews that God gave us our own: but above all, the fact that another man had the power to tear from our cradle the new-born babe and sell it in.” William Craft wrote.

With that thought lingering in the forefront of their minds, Ellen and William Craft began to plot their escape.

Wikimedia CommonsFamilies of slaves were regularly ripped apart at the auction block.

The Great Escape Plan

The Crafts’ plan was simple. They would utilize Ellen’s fair skin in order to disguise her as a white man traveling with his servant, William. The couple bought a ticket from Macon to Savannah using William’s saved cash. Their exodus comprised 200 miles aboard the very railroad system in which Ellen Craft’s owner invested.

Before embarking on Dec. 21, 1846, Ellen had her hair cut short and sewed herself into the duds of a wealthy planter. Her costume was accented with copious facial bandages and arm splints to reduce her chance of needing to talk with passengers and to explain away her inability to write. To complete the ruse, William was made to serve as the disguised Ellen’s slave.

Wikimedia CommonsEllen Craft dressed as a white man.

All was going well when the couple first boarded the train. Then, William Craft spotted a familiar face peering into the train cars — a cabinetmaker he’d met in his work. His heart stopped and he slunk into his seat fearing the worst.

Thankfully, the all-aboard whistle sounded providing the couple with a much-needed shield.

In the other train car, Ellen Craft had a similar scare. A good friend of her master’s happened to take a seat near her. She feared he had seen through her disguise, but eventually realized he hadn’t when he glanced over to her and commented: “It is a very fine day, sir.” Ellen Craft then pretended to be deaf the remainder of the ride to avoid speaking with him or anybody else again.

Ellen and William Craft reached Savannah unmolested. From there, they boarded a steamer headed to Charleston and even conversed with the ship’s captain over a congenial breakfast. He complimented William and ironically cautioned him against abolitionists who may convince him to make a run for his freedom. Once in Charleston, Ellen Craft arranged a stay at the town’s best hotel. She was treated with the utmost respect reserved for the likes of white planters she pretended to be. She was given a fine room and a luxurious seat for all her meals.

Eventually, they made it to the border of Pennsylvania. Though the state was free, border patrol was tough, and the couple hit a snag when it seemed they wouldn’t be allowed to enter. But a patrolman took pity on Ellen Craft’s bandaged arm and let them through. As the couple spotted the City of Brotherly Love, Ellen cried out: “Thank God, William, we’re safe!”

Taste Of Freedom

When they arrived in Philadelphia, the underground abolitionist network provided the Crafts with housing and literacy lessons. They traveled to Boston and took up jobs — William as a cabinetmaker and Ellen as a seamstress. For a time, all seemed well.

Then the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 unraveled their lives.

The Act was instituted as a part of the Compromise of 1850, which sought to appease Southern slaveholders. The Act gave permission to bounty hunters to find and return escaped slaves to their masters. It proclaimed that “when a person held to service or labor in any State or Territory of the United States…to whom such service or labor may be due…may pursue and reclaim such fugitive person.”

Runaway slaves like the Crafts were thereby considered fugitives and could be returned to slavery at any time should they be captured. The Act gave legal authority to slave hunters to kidnap slaves in the North and drag them back to the conditions they fought so hard to escape. With some notoriety in abolitionist circles, the Crafts had a target on their backs, particularly when President Millard Filmore threatened to use the full might of the U.S. Army to return slaves into bondage.

The Crafts subsequently fled to Britain, which William described as “a truly free and glorious country; where no tyrant…dare come and lay violent hands upon us” until the end of the American Civil War, upon which time they returned to the South. While abroad, however, in the country they felt so free, the Crafts went back on their earlier decision not to have children. They bore five.

Upon their return, the Crafts established and ran a South Carolina farm until the KKK burned them out in the 1870s. The family restarted in Georgia and opened the Woodville Co-operative Farm School for freed blacks.

The Crafts spent the remainder of their years tirelessly raising awareness on the cause of abolition and helping to educate and secure employment for freedmen and women. Though Ellen Craft died in 1891 and William on Jan. 29, 1900, their story of immense courage and ingenuity persists.

Check out more stories about slavery and the Civil War with this Civil War photo gallery and then continue on to these touching and heart-wrenching slavery love letters.