From 1943 to 1944, Elyesa Bazna worked as a valet for the British ambassador to Turkey. But behind the scenes, he photographed secret documents and gave them to the Nazis.

Elyesa Bazna had led a rambling, aimless life for 40 years, working as a driver for the French Army, a locksmith for a French carmaker, and even briefly as a professional opera singer.

But in April 1943, he found himself a middle-aged servant at the embassies in Ankara, Turkey, and began to wonder if that was all he’d ever be.

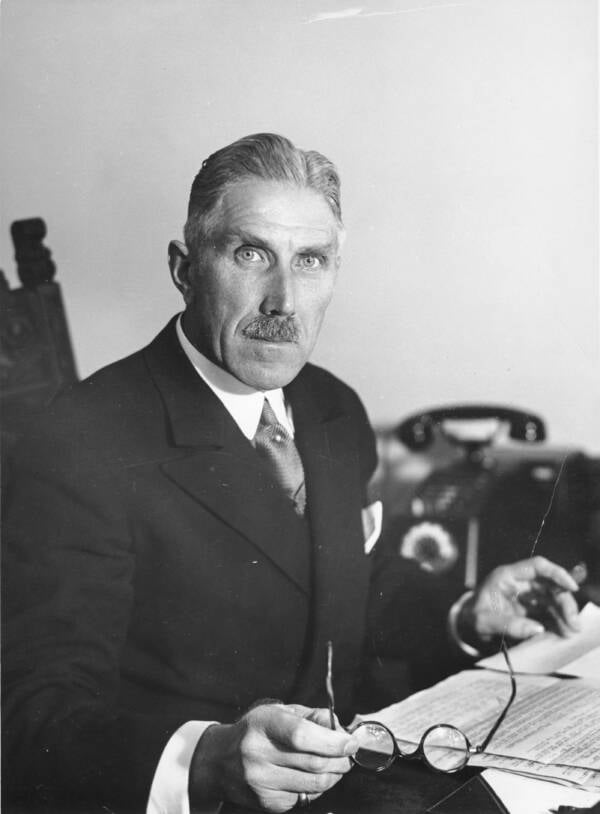

Wikimedia CommonsUnsatisfied with his life as a servant to the British ambassador to Turkey, Elyesa Bazna sought his fortune by stealing his employer’s documents and selling them to the Nazis for breathtaking prices.

As he sat reading the newspaper and drinking coffee in the lounge of the Ankara Palace Hotel, “suddenly, out of the midst of all this gloom, there came an electrifying idea:” He would take advantage of his invisibility to steal valuable secrets from Britain to make his fortune. He set off to apply for a position, and resolved to “sell my services more dearly than anyone else did.”

This is the story of Elyesa Bazna, the spy who nearly handed Hitler victory over the Allies.

Elyesa Bazna Infiltrates The British Embassy

Australian War MemorialSir Hughe Knatchbull-Hugessen, seen here between the two men in uniform, was Britain’s ambassador in Turkey from 1939 to 1944.

When Elyesa Bazna was first presented to Sir Hughe Knatchbull-Hugessen, British Ambassador to Turkey, he seemed perfect. He came highly recommended, spoke French, was a good driver and mechanic, and carried glowing references from the American military attache in Ankara and the ambassador of Yugoslavia.

Assuming Bazna’s background had been checked, Knatchbull-Hugessen hired him as his valet on the spot. Later, the music-loving ambassador was convinced he’d made the right choice when he discovered his new servant had a fine singing voice, and had even given a professional concert once.

Bazna prepared the ambassador’s clothes, helped him wash and dress, and was at his beck and call for anything he needed, including standing watch outside of his study door to deter unwanted visitors. On special occasions, Knatchbull-Hugessen dressed his servant in “richly embroidered brocade, shoes with turned up toes, a fez with a tassel … an immense scimitar, and placed him on the main door.”

Knatchbull-Hugessen had no way of knowing that Bazna had been fired from his previous job working for the German ambassador for taking photos of documents there. He also couldn’t have known that on Oct. 26, 1943, Bazna acted on his promise to himself and made a phone call to the German embassy.

Going To Work For The Germans

BundesarchivElyesa Bazna sold his photographs to German ambassador Franz von Papen, one-time German chancellor who’d persuaded President Paul von Hindenburg to invite Adolf Hitler into the government,

On Oct. 25, Bazna took photographs of official documents in the kitchen of Douglas Busk, his first British employer and the man who’d referred him to Knatchbull-Hugessen. Because he could neither speak nor read English, Bazna had no idea what was on the pages he stole.

It must have seemed valuable to the Germans, though, because Ambassador Franz von Papen was authorized to pay Bazna’s exorbitant price of £20,000 — nearly $1.4 million today — for the first set of documents, and £15,000 for each additional sale. He hid the proceeds under the carpet in his room at the British embassy.

Bazna’s work was made easier by Sir Hughe’s casual attitude to security. British diplomats were supposed to follow strict regulations for protecting sensitive documents, including keeping them in locked safes in their official, guarded offices. Sir Hughe preferred to take his work home with him, keeping top-secret documents in his personal safe.

As a trained locksmith and with Sir Hughe’s trust, Bazna had no problem swiping the keys one morning while his employer was in the bath, making wax impressions of them for later copies.

Once von Papen realized how valuable his new source was, he decided that it was worth the expense to keep Bazna on retainer. He also assigned the spy a new code name. Since the documents he’d provided were “so very, very eloquent, let’s call him Cicero,” he said.

Eleysa Bazna Lays The Allies’ Secrets Bare

Wikimedia CommonsSoviet and Russian sources have long claimed that the Nazis used Bazna’s information to plan the murder of Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin in 1943.

The first batch of film Bazna sold to the Germans contained the minutes of the third Moscow Conference, at which senior Allied leaders met to discuss the progress and planning of the war. Cicero had unlocked a door into the highest ranks of the Nazis’ enemies.

He carried on with his photographs, keeping Knatchbull-Hugessen at ease with his apparent personal loyalty and eagerness to sing for guests while the ambassador played the piano. Throughout late 1943, Bazna stole dozens of documents marked “Most Secret” and “Top Secret,” adding to his fortune with each sale.

Among the secrets he revealed were that Franklin Roosevelt had raised the idea of Germany’s unconditional surrender as the only option for peace, as well as details of further Moscow conferences and conferences in Tehran and Cairo. Although these were important, none of them contained the same degree of information as the Moscow minutes.

Unable to read English, Bazna played it safe and took photos of everything he could get his hands on, “from the ambassador’s Christmas list to private correspondence with King George VI.”

The steady flow of information was noticed by Allied intelligence in December 1943. Bazna even photographed a message to Knatchbull-Hugessen warning him of a leak in his embassy. When British counterintelligence officers arrived to interview the embassy staff, Bazna escaped suspicion because they thought “the valet was too stupid to make a good spy and did not, in any case, speak or understand English.”

How The Germans Wasted Bazna’s Intelligence

Otto Skorzeny, seen here with Benito Mussolini, the SS’ star commando some claim would have assassinated the Allied leaders at the Tehran Conference.

The only evidence that the Nazis ever intended to act on “Cicero’s” information was an alleged plot to send SS commandos to the Tehran Conference to assassinate Winston Churchill, Joseph Stalin, and Franklin Roosevelt. However, “Operation Long Jump” was never carried out, and there are doubts that it ever existed at all.

Many of the secrets Bazna sold the Germans became lost in the bureaucratic infighting that characterized the Nazi regime. Von Papen and his boss, Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop, hated one another, and secret police chief Ernst Kaltenbrunner loathed both of them. The Abwehr, military intelligence, was envious of the SS Security Service’s control of the Cicero operation and worked to hamper it.

On top of that, many Nazi leaders believed Cicero’s documents were too high-quality, and must have been fakes — and even those who believed in them failed to act.

If they’d paid closer attention, they might have noticed that in late 1943, one word began showing up in Bazna’s documents more and more frequently: “Overlord.” When Bazna and his handler, Ludwig Carl Moyzisch, realized that this word referred to the planned invasion of Western Europe, they wired Berlin to report their suspicions, only to be told that the connection was “possible but hardly probable.”

On June 6, 1944, the Allies began landing more than 2 million troops on the shores of Normandy, heralding the beginning of the end of fascist rule in Europe. German military planners ignored the many warnings and clues they’d obtained from Cicero, deploying troops to the wrong areas, and were ultimately defeated.

Fortunately for the Allies, the Germans’ failure to appreciate their best resource left them unprepared.

The End And Aftermath Of Operation Cicero

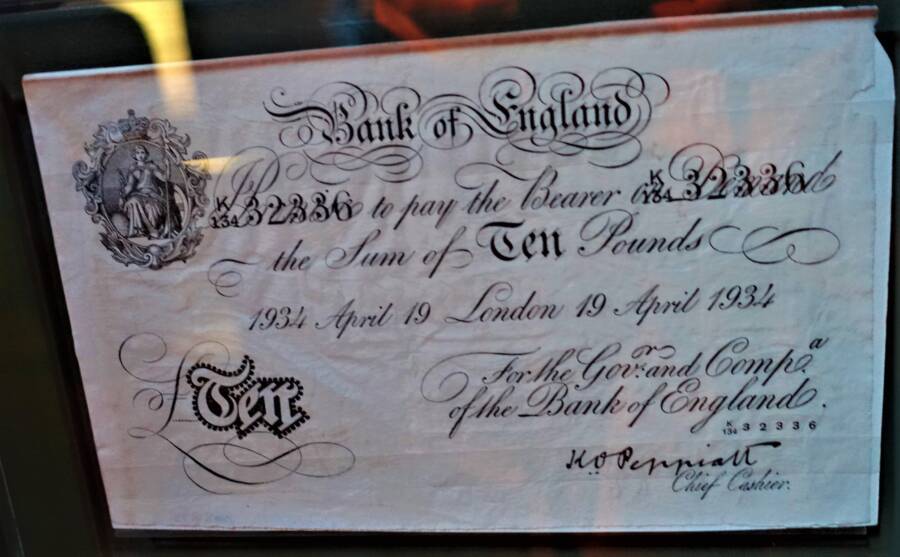

Wikimedia CommonsAs many as half of the notes Bazna received were forgeries like this one, created under the direction of the SS in Sachsenhausen concentration camp.

In January of that year, the handler, Moyzisch, hired a new secretary, whom he knew as “Elisabet.” In reality, she was Cornelia “Nele” Kapp, daughter of the German consul in Cleveland, Ohio. A few weeks before, she’d offered to spy on her countrymen for the American Office of Strategic Services in return for safe passage to the United States.

Kapp followed and watched Moyzisch and Bazna several times between January and April 1944. Although she never managed to get a good look at the face of the man her boss was meeting with, she gathered extensive circumstantial evidence against Cicero.

Between her vigilance and the British effort to tighten security at the embassy, Bazna soon found it impossible to gather information any longer. Probably sometime in March, he handed in his resignation and left the embassy for good.

Only later did Bazna realize that much of the £300,000 he’d received from the Germans was worthless. He’d been paid in crisp, new British pound notes forged by inmates of Sachsenhausen concentration camp. The discovery of Nazi counterfeiting operations meant banks were far more careful about fakes. The Nazis had cheated Bazna out of a fortune worth more than $17 million today.

Bazna inspired numerous spy stories, most directly the 1952 film 5 Fingers, starring James Mason as a character based on Cicero. But apart from releasing his memoirs, Bazna spent much of the remainder of his life in obscurity, working as a night watchman in Munich.

Hitler had planned to give him a villa after the end of the war. Instead, Elyesa Bazna died penniless on December 21, 1970, aged 66. His petition to the West Germans for a pension had been denied.

Now that you’ve learned how Elyesa Bazna’s greed nearly led to a Nazi victory, read the thrilling story of Eddie Chapman, alias “Agent Zigzag,” the most successful double agent of the Second World War. Then, find out more about how the Allies used an array of brilliant tricks to deceive the Axis in Operation Quicksilver.