From 180 to 192 C.E., Emperor Commodus ruled ancient Rome with an insatiable lust for power that brought an end to the fabled Pax Romana.

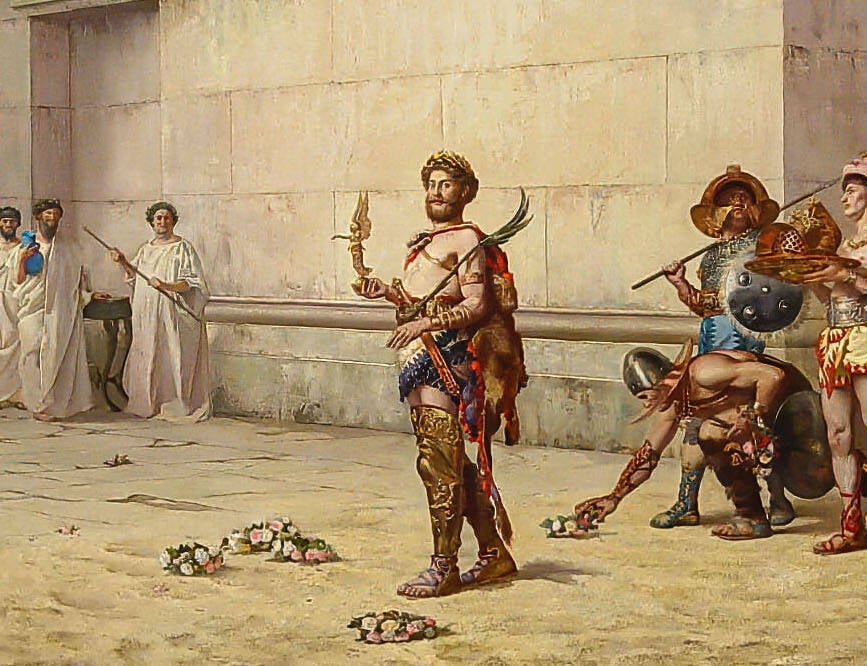

Wikimedia CommonsEmperor Commodus leaving the gladiator arena after one of his many staged bouts.

The long line of ancient Roman emperors is marked by a strange pattern: Almost every exceptionally brilliant emperor was succeeded by an exceptionally mad one.

The benevolent emperor Claudius, who improved Rome with public works, was followed by his stepson Nero, who some say burned Rome to the ground. The emperor Titus Flavian completed the Colosseum and endeared himself to the public with his generosity only to have his good works undone by his brother Domitian, who was assassinated by his own court.

And the wise Marcus Aurelius, known as the “Philosopher” and the last of the “Five Good Emperors,” would be succeeded by his son Commodus, whose descent into madness would be immortalized throughout the millennia (including a heavily fictionalized account in the popular 2000 film Gladiator).

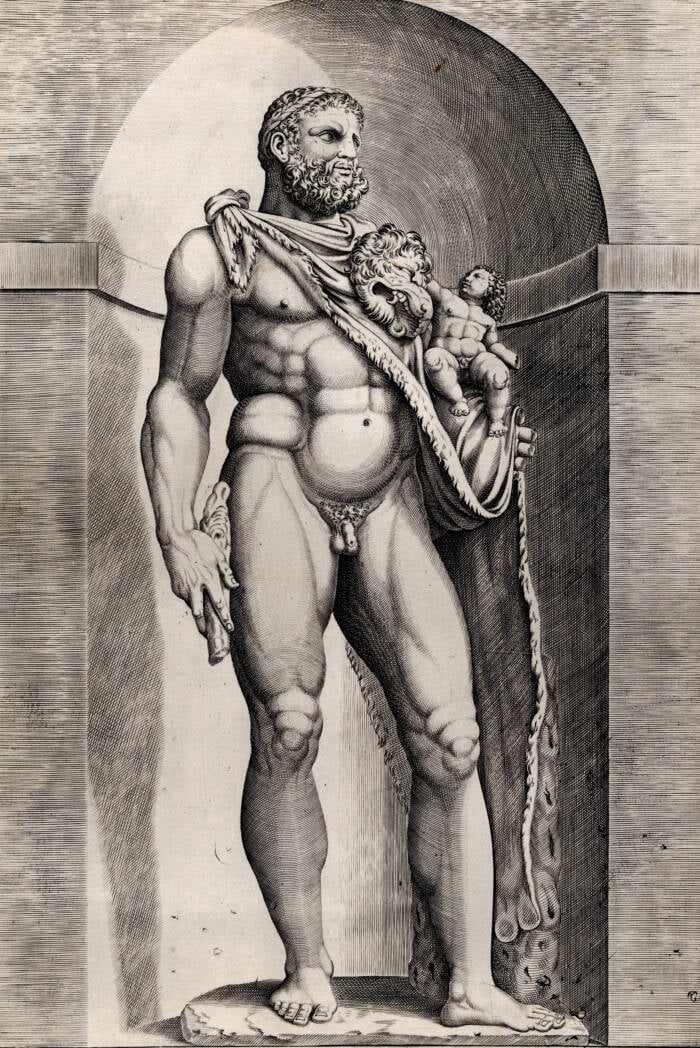

Wikimedia CommonsA bust of Roman Emperor Commodus, styled as if he were a reincarnation of Hercules, which is precisely what he believed himself to be.

As Edward Gibbon noted in his famous Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, in the intervening years between the death of Domitian and the reign of Commodus, “the vast extent of the Roman empire was governed by absolute power, under the guidance of virtue and wisdom.” The “Five Good Emperors,” ruled efficiently and under them the Roman people enjoyed “a rational freedom.”

However, just when the days of the mad emperors seemed long gone, Commodus brought the madness roaring back.

Commodus Takes The Throne After The Death Of Marcus Aurelius

Wikimedia CommonsA bust Of Commodus as a boy, before becoming emperor.

Lucius Aurelius Commodus, born 161 C.E., was raised during the years of the Antonine Plague and appointed co-emperor by his father Marcus Aurelius in 177 C.E. when he was just 16 years old. Contemporary Roman writer Cassius Dio describes the young heir as “rather simple-minded,” but he ruled agreeably with his father and joined Marcus Aurelius in the Marcomannic Wars against the Germanic tribes along the Danube, which the emperor had been waging for several years.

But once Marcus Aurelius died in 180 C.E. (of natural causes, not at his son’s own hand, as depicted in Gladiator), Commodus hastily made peace with the tribes so he could return to Rome “to enjoy the pleasure of the capital with the servile and profligate youths whom Marcus had banished, but who soon regained their station and influence about the emperor.”

Wikimedia CommonsThe death of Marcus Aurelius, father of Commodus.

Despite his unusual personal tastes, Commodus at first behaved more like a typical spoiled, rich youth than a bloodthirsty dictator. Cassius Dio declared that Commodus “was not naturally wicked” but that “his cowardice, made him the slave of his companions.”

He kept most of the advisers from his father’s regime in place and the first three years of his reign ran as smoothly as that of his father with the added benefit that Rome was no longer fighting any wars. In fact, the rule of Commodus might have gone down as quite unremarkable in the history of Rome were it not for one unfortunate incident.

An Assassination Attempt Fuels Commodus’ Descent Into Madness

In 182 C.E., Commodus’ sister Lucilla organized an attempt on her brother’s life. Sources diverge on the origins of the conspiracy, with some claiming Lucilla was jealous of Commodus’ wife Crispina (a sexual relationship between Commodus and Lucilla is suggested in Gladiator) while others maintain she saw the first warning signs of her brother’s mental instability.

Lucilla, the sister of Commodus who tried to have him killed.

Whatever its roots, the conspiracy failed and the incident aroused an insane paranoia in Commodus, who began seeing plots and treachery everywhere. He executed the two would-be assassins along with a group of prominent senators who were also allegedly involved while Lucilla was exiled to Capri before also being killed on her brother’s orders a year later.

The assassination attempt marked a turning point in Commodus’ reign, for “once [he had] tasted human blood, he became incapable of pity or remorse.” He began executing people without regard for rank, wealth, or sex. Anyone who caught the emperor’s attention risked also inadvertently invoking his wrath.

The emperor eventually decided to abandon “the reins of the empire” and chose to give “himself up to chariot-racing and licentiousness and performed scarcely any of the duties pertaining to his office.” He spent hardly any time in Rome, instead appointing a series of his favorites to manage the administration of his empire, each of whom seemed crueler and more incompetent than the last.

However, even these favorites were not safe from his fury. The first, Sextus Tigidius Perennis, Commodus put to death after becoming convinced he was conspiring against him. The second, the freeman Cleander, he allowed to be torn apart by a mob of Roman citizens who were outraged at the freeman’s abuses. The emperor’s own family members faced his brutality, too, and both his cousin and brother-in-law were also put to death.

While Commodus likely didn’t murder any of his enemies himself, he did have a penchant for killing — and he took it out on wild animals.

The Mad Emperor’s Megalomania As A “Gladiator” In The Colosseum

New York Public LibraryCommodus enters the Circus Maximus.

Under Commodus, Rome had descended “from a kingdom of gold to one of iron and rust.” Much like Nero had supposedly fiddled while Rome burned, Commodus enjoyed himself as the city decayed around him.

The executions of the senators had whet his appetite for blood and he devoted himself “to combats of wild beasts and of men.” Not merely content to hunt in private, the emperor began to perform in the Colosseum itself, competing as a gladiator to the delight of the crowds and horror of the senate, as depicted in Gladiator. Commodus would “enter the arena in the garb of Mercury and casting aside all his other garments, would begin his exhibition wearing only a tunic and unshod.”

Wikimedia CommonsEmperor Commodus’ lust for power is widely credited with bringing an end to the fabled Pax Romana.

As disgusted as the senators were by the sight of their emperor running around half-naked in the sands of the amphitheater, they were too terrified to do anything but play along. Cassius Dio recorded one incident in which, after becoming tired out, Commodus ordered a cup of chilled wine to him and “drank it at one gulp.” In an amusing anecdote, Dio continued, “At this both the populace and we senators all immediately shouted out the words so familiar at drinking-bouts, ‘Long life to you!'”

There was seemingly no limit to what the emperor would battle in the arena. Dio wrote that Commodus once “dispatched five hippopotami together with two elephants on two successive days; and he also killed rhinoceroses and a camelopard [giraffe].” Another time, he slew 100 bears from the safety of a balcony.

However, Commodus wasn’t quite as fearsome as he imagined himself. By one account, he cut off the head of an ostrich and presented it to the senators who were watching from the stands. “He spoke not a word,” Cassius Dio stated, “yet he wagged his head with a grin, indicating that he would treat us in the same way. And many would indeed have perished by the sword on the spot, for laughing at him (for it was laughter rather than indignation that overcame us), if [we] had not chewed some laurel leaves… so that in the steady movement of our armies we might conceal the fact that we were laughing.”

The megalomania of Commodus was not limited to the Colosseum, however. “So superlatively mad had the abandoned wretch become” that he renamed Rome Colonia Commodiana (the Colony of Commodus) and changed the names of the months to each reflect one of the many epithets he had bestowed upon himself.

The MetA statue of Commodus in the style of Hercules.

He also declared himself to be an incarnation of the god Hercules and forced the senate to recognize his divinity. Statues were erected of the emperor depicted as the mythological hero all over the city, including one made of solid gold and weighing in at nearly 1,000 pounds.

In one final act of madness, Commodus ordered the head of the Colossus of Nero to be replaced with his own and added the inscription “the only left-handed fighter to conquer twelve times (as I recall the number) one thousand men.”

The Murder Of Commodus And His Legacy To This Day

By 192 C.E., the Roman people had had enough. “Commodus was a greater curse to the Romans than any pestilence or any crime” and the city had descended into bankruptcy and chaos. A small group of conspirators, including the emperor’s chamberlain and mistress, Marcia, decided to kill him. The first attempt used poisoned meat, but Commodus vomited it up.

Yet another attempt on his life had been foiled, but the conspirators did not lose their nerve. They then sent in a wrestler named Narcissus to strangle the 31-year old emperor in his bath. It worked. The Nerva-Antonine dynasty which had ruled Rome for nearly a century came to an end, and the city soon descended into civil war. Commodus ruled with chaos and left chaos in his wake.

He is widely remembered as one of the worst Roman emperors to this day, and his rule is often seen as the end of a golden age that never returned before the fall of Rome.

DreamWorksEmperor Commodus as played by Joaquin Phoenix in the 2000 film Gladiator.

His astounding story was depicted via Joaquin Phoenix’s portrayal in the 2000 film Gladiator, though Hollywood took several creative liberties. Commodus did not kill his own father, and he certainly didn’t die during a duel in the Colosseum. Indeed, the film’s protagonist Maximus is a completely fictional character. There is also no evidence that the emperor desired a sexual relationship with his sister Lucilla as hinted at in the film. Indeed, Lucilla was exiled and put to death long before Commodus began competing as a gladiator.

Still, the movie captures just how egotistical, unhinged, and cruel Commodus truly was. He left behind a disturbing legacy as one of Rome’s worst emperors — and an indelible bloodstain on the empire’s history.

After this look at Commodus, check out these interesting facts about ancient Rome. Then, discover the most fascinating facts from the entirety of ancient history.