For about two centuries, the Roman Empire thrived during a period of relative peace known as the Pax Romana — but it didn't last.

North Wind Picture Archives/Alamy Stock PhotoA depiction of “art and education” under Augustus, Rome’s first emperor, during the Pax Romana.

In modern times, the term Pax Romana — a period spanning from 27 B.C.E. to 180 C.E. — may seem inaccurate, especially since there was some violence and unrest during the era. However, for many ancient Romans themselves, it was viewed as a time of relative peace and prosperity.

Still, the Roman historian Tacitus famously painted a tumultuous picture of the Pax Romana period in his account Histories: “The history on which I am entering is that of a period rich in disasters, terrible with battles, torn by civil struggles, horrible even in peace. Four emperors fell by the sword; there were three civil wars, more foreign wars, and often both at the same time. There was success in the East, misfortune in the West.”

Yet despite these upheavals, the Pax Romana symbolized a shift toward stability after the tumultuous end of the Roman Republic. The Pax Romana, kickstarted by Rome’s first emperor Augustus after his defeat of Mark Antony and Cleopatra in 31 B.C.E., ushered in a new age of Roman history. In this new time period, military conflicts were less frequent, public works flourished, and many new social reforms were enacted.

While the empire was not without strife, this era ushered in a sense of peace for many Romans that allowed their society to reach new heights.

The Deaths Of Mark Antony And Cleopatra — And The Beginning Of The Pax Romana

Public DomainThe Battle of Actium, by Laureys a Castro. Circa 1672.

In 32 B.C.E., the Roman Republic was on the brink of war. Octavian, Julius Caesar’s great-nephew and adopted son, had already risen to great power in the Roman Republic alongside Mark Antony and Lepidus.

Meanwhile, Antony, who held power in Egypt, which was virtually a client kingdom of Rome, was in a relationship with Egypt’s queen, Cleopatra.

Ever since 51 B.C.E., Cleopatra had ruled over Egypt, initially alongside her brothers (whom she likely married at different points). Her relationship with her siblings was strained, especially as she emerged as the dominant ruler.

In 41 B.C.E., Cleopatra and Mark Antony connected and soon began a torrid love affair that infuriated Octavian, who was the brother of Antony’s wife, Octavia the Younger. Antony and Cleopatra had three children together, including a daughter, Cleopatra Selene II, and two sons, Alexander Helios and Ptolemy Philadelphus. Meanwhile, Cleopatra’s eldest son, Caesarion, was believed to have been fathered by the recently assassinated Julius Caesar.

Antony’s unabashed support of and dedication to Cleopatra led to a growing divide among Rome’s elites, culminating in a civil war by 31 B.C.E.

Octavian and Antony’s forces clashed at the Battle of Actium, resulting in a major loss for the star-crossed lovers. Instead of surrendering to Octavian, Cleopatra and Antony died by suicide in 30 B.C.E., paving the way for Octavian to become the very first emperor of Rome.

Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 4.0A statue of Augustus, the first emperor of the Pax Romana.

In 27 B.C.E., Octavian ascended to the Roman throne as Augustus. His rule marked the end of the Roman Republic and the start of the Roman Empire.

As the first leader of a new era in ancient Rome, Augustus faced numerous challenges legitimizing his rule. Despite declaring himself princeps, meaning first citizen, Augustus also created a council of military officials to lead alongside him. This move not only made Augustus’ government more recognizable, but also helped to prevent the outbreak of civil war.

In a ceremonial display representing a new era in Roman history, Augustus had the gates of the Temple of Janus closed in 29 B.C.E. Historically, the gates represented times of peace and war in Rome. When they were opened, Rome was at war; when they were closed, Rome was at peace.

These ceremonies were part of Augustus’ efforts to reframe the way Romans viewed times of peace. For a state that had been at near-constant conflict for over 200 years, peace was likely considered alien, unnatural, and perhaps even counterproductive to many Romans. Augustus was eager to launch a propaganda campaign aimed at redefining peace for his new Roman Empire, but that first required making peace — or at least relative peace — a reality.

Not only did he prioritize settling conflicts in Rome’s outlying territories, but he also put forth effort to make the Roman Empire a pleasant place to live.

Under Augustus’ reign during the Pax Romana, Rome saw the building of numerous new temples, aqueducts, baths, theaters, and parks. He viewed his impact on the city as so profound that, as he lay dying in 14 C.E., he declared, “I found a Rome of bricks. I leave to you one of marble.”

After Augustus’ death, the Pax Romana continued for about two centuries, supported by a series of rulers later known as the “Five Good Emperors.”

Turbulence Before Rome’s “Five Good Emperors”

Public Domain A bust of Trajan, one of the “Five Good Emperors.”

After Augustus’ death, the Roman Empire was plagued by a series of rulers who failed to live up to the political and social standards that Augustus had set. Augustus’ successor, Tiberius, was not well-liked among the state’s elites, and he also had a reputation for being reclusive. Many of his contemporaries accused him of being a tyrannical ruler, and some Roman historians even alleged that he was a depraved sexual predator.

Upon his death in 37 C.E., Tiberius was succeeded by Caligula, his adopted grandson. Caligula proved to be a terrible leader whose tyrannical rule drove the Roman Empire toward economic crisis. His assassination in 41 C.E. by a group of guards was only a brief reprieve from Rome’s political struggles.

The next leader of the Pax Romana was Claudius, Caligula’s uncle. Under Claudius’ reign, the Roman Empire expanded into North Africa, and Britain was also made into a province. In Rome, aqueducts and roads were built, and Claudius also made improvements to the judicial system.

But then, in 54 C.E., Claudius was poisoned by his niece and wife Agrippina, paving the way for one of Rome’s most infamous rulers. When Agrippina’s son Nero ascended to the throne, he was only 16 years old. His mother guided the young ruler alongside several tutors and advisors.

Despite the group’s efforts, Nero gained an infamous reputation as a tyrant with a penchant for debauchery. He spent lavishly on festivals and other pleasures, leading to financial strain on the empire. His mismanagement of both economics and foreign policy eventually led to public disdain so great that he was forced to flee Rome and die by suicide in 68 C.E.

Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 2.5A coin from Nero’s reign, showing the Temple of Janus.

For nearly 30 years, Rome struggled with internal conflict as warring generals fought for the opportunity to rise to power. Over the course of just one year, three men attempted to be the ruler of Rome before they were murdered.

However, Emperor Trajan’s ascension in 98 C.E. marked a calmer era for Rome. He was the second of the “Five Good Emperors,” taking the throne after the first, Nerva, who had established a newfound sense of stability in the empire, despite serving less than two years as emperor.

Under Trajan’s rule, the Roman Empire became larger than it ever was before. Not only did Trajan conquer Dacia (part of modern-day Romania), but he also captured land that is now part of Iran. The empire stretched across Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa, including modern-day Israel, Turkey, Lebanon, Syria, and parts of modern Iran and Iraq and even Scotland. Trajan also improved Rome’s infrastructure and created a great forum and market, a small section of which still stands to this day. His rule helped reinvigorate hope for the future of Rome during the Pax Romana.

Hadrian, Marcus Aurelius, And The Eventual End Of The Pax Romana

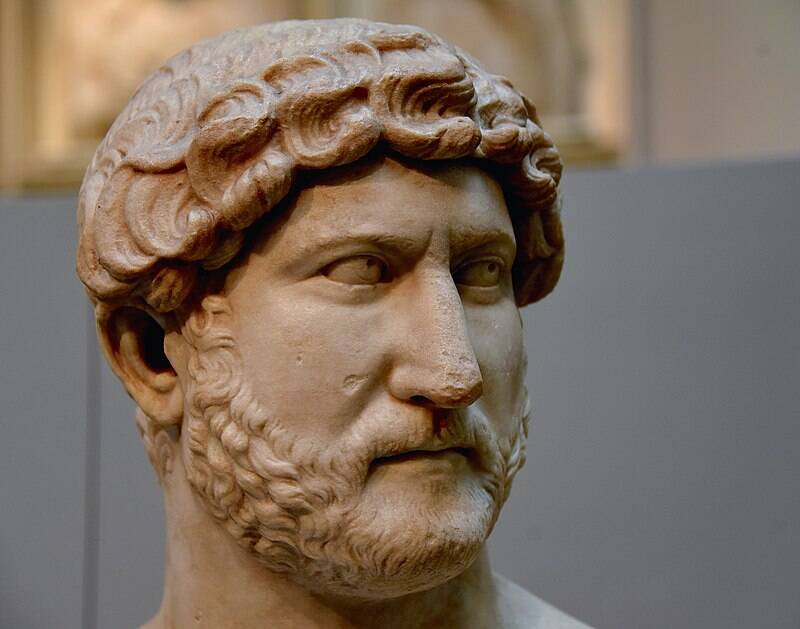

Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 4.0A bust of Emperor Hadrian.

Hadrian ascended to the Roman throne in 117 C.E. Unlike Trajan, Hadrian was not an expansionist. Instead, he focused on strengthening Rome’s power over its most important territories and securing the empire’s borders.

The emperor oversaw several building projects, including Hadrian’s Wall in Britain and rebuilding the Pantheon in Rome. Most of his time was spent traveling across Rome’s territory, visiting each province to examine their government figures, military capabilities, and unique customs.

Most importantly, Hadrian established a clear line of succession. He handpicked Antoninus Pius to be his successor, and he also declared that Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus would succeed Antoninus Pius.

During the reign of Antoninus Pius, the Pax Romana arguably reached its peak. The Roman Empire was at peace, with relatively good government and no major foreign wars occurring. Pius continued his predecessors’ legacy of improving public works and following through on the line of succession.

In 161 C.E., Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus became the emperors of Rome. Unlike Antoninus Pius before them, the two rulers did engage in some military conflicts, including a conflict with the Parthian Empire.

Public DomainA depiction of Marcus Aurelius handing out bread to the people of Rome.

In 165 C.E., the Antonine Plague began spreading through the empire, eventually killing an estimated 5 to 10 million people by the time the epidemic receded around 180. Lucius Verus died in 169, though his cause of death was a stroke, leaving Marcus Aurelius to rule the empire alone.

The impacts of the plague were immense. Agriculture production collapsed, leading to food shortages, and many Romans suddenly became desperate for food. Meanwhile, domestic and international trade was also disrupted, as the expenses increased for general maintenance of the massive empire.

Before his death in 180, Marcus Aurelius named his son, Commodus, as his successor. The decision to choose his own son, a power-hungry man who would later be driven mad after an unsuccessful assassination attempt, would spell the end of the Pax Romana and, as Roman historian Cassius Dio stated, take Rome “from a kingdom of gold to one of iron and rust.”

After reading about the Pax Romana, learn why the Roman Empire fell and when it collapsed. Then, read about Rome’s most famous gladiators.