Both Canada and Denmark claimed Hans Island as their own, and the nations fought the amicable "Whiskey War" by leaving spirits for each other on the island until they agreed to share the territory in 2022.

Toubletap/Wikimedia CommonsHans Island is 11 miles from both Canada and Greenland.

For decades, a little-known war raged in the Arctic. Called the “Whiskey War” or the “Liquor Wars,” it was fought over a tiny piece of uninhabited land called Hans Island, located between Canada and Greenland. The war had no battles and no casualties. But though bloodless, the conflict over Hans Island did cause a “freeze” between the two countries.

The island isn’t much to look at. Rocky and barren, often encircled by Arctic ice, Hans Island boasts just half a square mile of territory. It’s long been a hunting ground for the Greenlandic Inuit, but no one actually lives there — and the rocky terrain would make doing so difficult.

Despite this, Denmark and Canada squabbled over ownership of Hans Island for decades. In fact, it was only in 2022 that their dispute over the island was finally resolved for good.

A Tiny Island In The Middle Of The Arctic

Located in Nares Strait between the northernmost points of Canada and Greenland (an autonomous territory of Denmark) Hans Island was long used by Greenland’s indigenous Inuit to hunt polar bears, track ice floes, and monitor caribou herds. They called the island Tartupaluk. And, indeed, Hans Island did not even appear on Western maps until the late 19th century.

In the 1870s, the doomed American explorer Charles Francis Hall directed his ship, Polaris, to sail through the Kennedy Channel of Nares Strait en route to the North Pole. His guide, a Greenlander named Hans Hendrik, spotted the island during their journey, and Hall named it in his honor.

But which country owned Hans Island? Over the ensuing decades, both Canada and Denmark laid claim to the tiny, barren piece of rock.

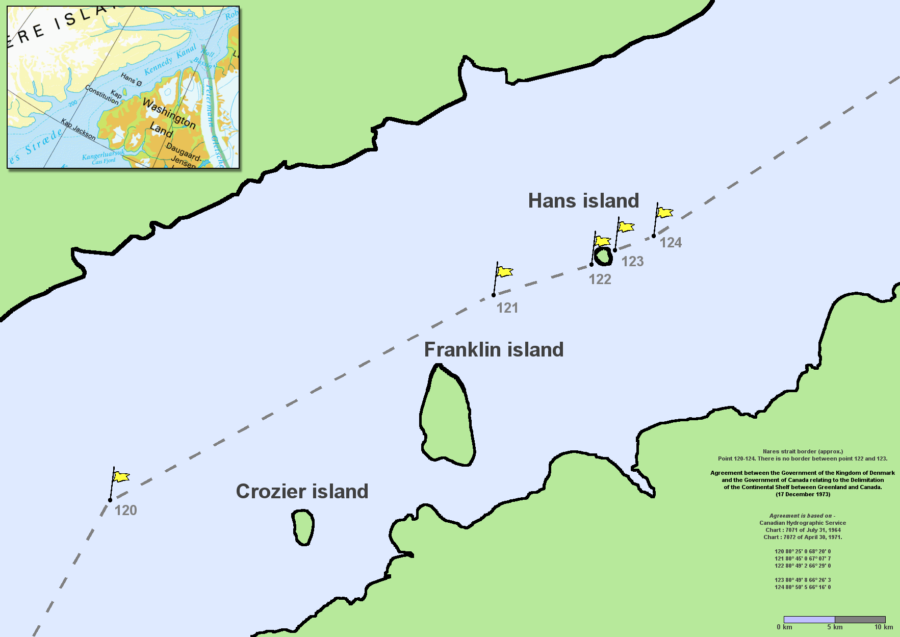

Lasse Jensen/Wikimedia CommonsA 1973 agreement drew a line through Kennedy Channel but was unable to resolve the dispute over Hans Island.

When Hans Island first appeared on a map in 1874, Britain controlled territory in the Arctic Archipelago. But in 1880, the British gave up their claim and turned their Arctic territories over to Canada. Danish sovereignty over northern Greenland, on the other hand, was established when the United States gave up its claim to the region following the purchase of the U.S. Virgin Islands from Denmark in 1917. So who owned Hans Island?

Denmark would contend that Hans Island was geologically part of Greenland and that the island was slightly closer to Greenland than Canada. (In fact, Hans Island is located about 11 miles from Canada’s Ellesmere Island and from Greenland). But the dispute between the two countries would stay at a low simmer until the 1970s during a negotiation about maritime borders.

NASAHans Island is often dwarfed by sea ice.

Though Canada and Denmark were able to agree on a dividing line between Nares Strait, they could not agree about who owned Hans Island. Both countries laid claim to it. Even a U.N. computer program could not resolve the dispute, as Hans Island fell directly between point 122 and point 123. According to the Peace Palace Library, no line connected the points.

Denmark and Canada agreed to solve their dispute over Hans Island at a later date. But in the next decade, the so-called “Whiskey War” would begin.

The ‘Whisky War’ Between Canada And Denmark

Per Starklint/Wikimedia CommonsThe Danish flag flying on Hans Island in 2003.

According to Denmark, the Canadians started it. According to Canada, it was the Danes who escalated the “war” over Hans Island.

In one version of the story, tensions over Hans Island escalated when a journalist from Greenland observed a scientist from a Canadian oil company surveying the area in 1983. Their article incited waves of protests from Greenland, and Denmark’s foreign minister subsequently flew to Hans Island, planted a Danish flag, and left behind a bottle of Danish schnapps.

In another, it was Canadian troops who landed on Hans Island in 1984, planted the Canadian flag, and left behind a bottle of Canadian whiskey.

Whoever began the “Whiskey War,” it would continue for the next several decades. The Canadians would leave whiskey; the Danes would leave aquavit, a Danish spirit. The Canadians would hoist their flag; the Danes would take it down and hoist their own. And so on and so forth.

Per Starklint/Wikimedia Commons The crew of the HDMS Triton left Cognac, pears, and Danish pork on Hans Island in 2003.

For two decades, this back-and-forth — described sometimes as “the friendliest of all wars” — continued. But things started heating up in 2005.

The Whisky War Over Hans Island Heats Up

In July 2005, Canadian soldiers raised their flag on Hans Island and built an Inukshuk, a type of Inuit stone cairn. One week later, Canada’s Defense Minister landed on the island during a tour of Arctic military outposts.

Canada’s attempt to assert its sovereignty in the Canadian Arctic did not go unnoticed by Denmark. The Danish ambassador to Canada published a letter in the Ottawa Citizen declaring that Hans Island belonged to Denmark. The Danish government also protested the Canadian’s move, summoned the Canadian ambassador, and sent the HDMS Tulugaq, a patrol vessel, to Hans Island, in a small but subtle show of force.

deadlyphoto.com/Alamy Stock PhotoHans Island on a clear day.

Despite the saber-rattling, however, neither country wanted the Whiskey War to escalate past taking down flags or leaving behind spirits.

“It is time to stop the flag war,” Anders Fogh Rasmussen, the Danish Prime Minister stated in August 2005. “It has no place in a modern, international world. Countries like Denmark and Canada must be able to find a peaceful solution in a case such as this.”

At the U.N. that September, Canada and Denmark also released a joint statement affirming their desire to work out a solution.

“We acknowledge that we hold very different views on the question of the sovereignty of Hans Island,” the two countries stated. “This is a territorial dispute which has persisted since the early 1970s, when agreement was reached on the maritime boundary between Canada and Greenland.”

However, both sides stopped short of giving up their claim to the island completely. They promised only that their “officials will meet again in the near future to discuss ways to resolve the matter.”

In other words, the dispute over Hans Island continued. And it would continue, quietly, until it finally came to an end 17 years later.

The Dispute Over Hans Island Comes To An End

International maritime law could not resolve the dispute over Hans Island. The law states that countries can claim any territories up to 12 nautical miles from their shore. But Hans Island fell within this 12-mile territorial limit.

So how did the Whisky War end? Through diplomacy.

In 2018, Denmark and Canada established a joint task force to study the issue, which also involved Inuit representatives. Their talks were productive. On June 14, 2022, the two nations agreed to share the island, with Denmark controlling 60 percent, and Canada the other 40 percent.

deadlyphoto.com/Alamy Stock PhotoAfter negotiations, Denmark and Canada agreed to share the island, with Denmark controlling 60 percent, and Canada 40 percent.

Referencing the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which had occurred just months before, Canada’s Foreign Affairs Minister Melanie Joly remarked that the agreement came: “at a very important time in our history because we know that authoritarian leaders believe that they can … draw boundaries by force…. Canada and Denmark and Greenland,” she added, “are sending a clear message to other Arctic states.”

The agreement pleased Inuit from Greenland and Nunavut, Canada’s Arctic territory, as well.

“Inuit have long used Hans Island as a staging point for hunting,” Lori Idlout, a member of Canada’s parliament representing the island who has called for Hans Island to be known by its indigenous name Tartupaluk, remarked. “We are pleased that the rights of Inuit have been protected so that they can maintain free movement and their traditional way of life.”

With that, the dispute over Hans Island was over. And to celebrate their new border — the longest maritime border in the world — Canada and Denmark indulged in one final exchange of spirits.

After reading about the Whiskey War, check out the shocking story of Ejnar Mikkelsen, who survived 28 months stranded in Greenland. Next, read about the secret military tunnels under Greenland’s ice.