Bloodthirsty crowds reveled in venationes that saw the mass slaughter of animals like lions, elephants, and bears as the Romans forever altered the ecosphere of an entire region.

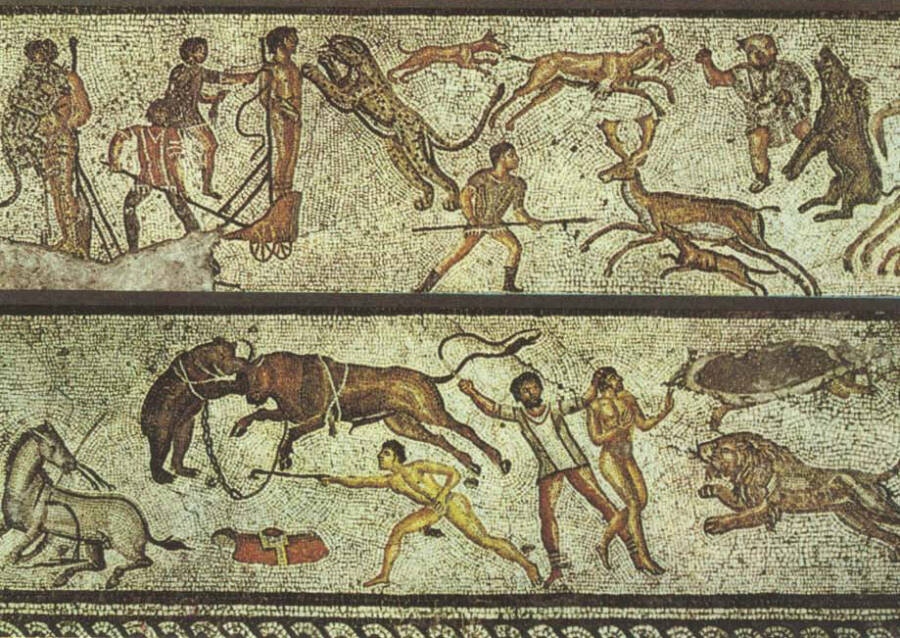

Wikimedia CommonsA mosaic depicting popular forms of entertainment in ancient Rome, including venationes.

In ancient Rome, nothing could spice up a night like attending a venatio. These battles, usually held at the Colosseum or in Circus Maximus, involved exotic animals like lions, bears, and hippos. Sometimes, the animals fought each other. Other times, they were pitted against venatores — warriors with weapons.

The plebians and patricians who filled the Colosseum’s stands weren’t the only ones who enjoyed such bloody events. Some emperors were so passionate about the venatio that they arranged spectacles that lasted more than 100 days. One had 500 lions killed in one fell swoop.

This is the history of venationes — the gruesome and brutal bloodsport that enthralled ancient Romans.

The Beginning Of Venationes In Ancient Rome

Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, Wikimedia CommonsPrint depicting the venationes held inside the Colosseum, made in the 17th century.

Audiences in ancient Rome had a taste for blood. They had long cheered on chariot races and gladiator matches. So it was no surprise that they were equally enthralled by venatio, which means wild animal hunt or staged hunt.

By some estimates, the venationes started as early as 252 B.C. Pliny the Elder describes a venatio that involved elephants that had been captured during the First Punic War.

However, it seems that Pliny’s elephants were not killed but merely displayed. After all, most Romans hadn’t seen an elephant before. The beasts were sometimes used in war but would have been completely foreign to a civilian.

The Roman historian Livy suggests that the first venatio took place a bit later, in 185 B.C. — after the Second Punic War. Then, the Roman general Marcus Fulvius Nobilior celebrated his victories in Greece by setting up a staged hunt.

“For the first time an athletic contest was on at Rome,” Livy wrote. “And a hunt was staged in which lions and panthers were the quarry, and the games were celebrated with practically all the resources and variety that the entire age could muster.”

The era of the venatio was at hand.

The Animals Of The Arena — And The Men Who Battled Them

Wikimedia CommonsA mosaic depicting the transportation of exotic animals.

To entertain the masses, Roman authorities summoned exotic animals from across their vast empire. They collected North African lions, panthers, and elephants, bears from Scotland, Hungary, and Austria, tigers from Persia, and crocodiles and rhinos from India.

Collecting the animals was difficult — and dangerous. After all, they needed to be brought back to Rome alive. The poet Oppian described one such bear hunt: the dogs used to hunt down the animal, trumpets used to confuse it, and how hunters would chase the beast into a net.

This was the most dangerous part, Oppian wrote, “for at that moment bears greatly rage with jaws and terrible paws.”

Hunters also used pits. They would draw an animal — maybe a tiger or lion — to a pit filled with bait. When the animal jumped in, the hunters would lower a cage into the pit to capture the animal.

Back in Rome, the creatures would be pitted against other animals. Or, sometimes, against men.

Most scholars differentiate two types of man-to-animal combat that took place in Rome. Shows which featured armed men fighting wild beasts were venatio. However, Romans would also throw men who were condemned to death into an arena with an angry bear or tiger — an idea they’d picked up from the Carthaginians.

So, who were the men who fought tigers, lions, and bears?

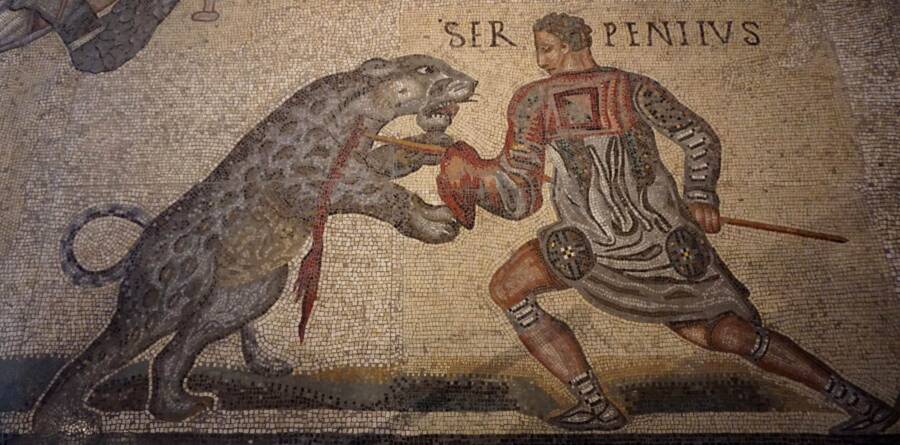

Pinterest/Galleria BorgheseA venatore fighting a leopard.

The venatores had much in common with Rome’s gladiators. Like gladiators, they were usually slaves, criminals, or under a contract to fight. But the venatores were considered to be even worse than gladiators (who often belonged to the lowest tier of society.)

However, like gladiators, the venatores trained for their encounters with wild animals. They would attend a ludus, or professional fighting school, before making their debut. Unlike the people condemned to death, they were allowed weapons to defend themselves.

At first, the animals were chained so that the venatores could easily kill them. But by 100 B.C., animals were often allowed to roam freely. This prompted the construction of high walls in the Colosseum so that the animals couldn’t climb out of the ring and attack the audience.

Inside The Bloody World Of Venationes

Pablo Salinas/Wikimedia CommonsHow a 20th century artist envisioned the Colosseum to have looked during Rome’s heyday.

Romans threw a venatio for multiple different reasons. Sometimes, the hunts were arranged to honor a deity, like Diana, the goddess of the hunt. Sometimes, they celebrated an anniversary, like a wartime victory. Often, the venationes marked a monumental occasion, like a wedding, a funeral, or the crowning of an emperor.

By around 80 A.D., the Romans had something big to celebrate — the inauguration of the Colosseum. The emperor Titus oversaw the event, which included a massive venatio that endured for more than 100 days. Romans cheered as over 9,000 animals were slaughtered during staged hunts.

Wikimedia CommonsA roman coin depicts a fight between a warrior and a boar.

Trajan, who became emperor in 98 A.D., wanted to break Titus’s record. His venatio, held in honor of Rome’s crushing defeat of the Dacians, lasted more than 120 days — and saw the slaughter of 11,000 animals. That’s more than 90 animals a day, for three straight months.

Some rulers enjoyed participating in the venationes themselves. Commodus, who ruled the Roman Empire from 177 until his assassination in 192 A.D., eagerly leaped into the ring. Known as a gladiator and amateur venatore, Commodus especially liked to think of creative ways to kill animals. He invented a crescent-shaped arrow to kill ostriches. Roman crowds went wild at the sight of the headless birds running around.

Marie-Lan Nguyen/Wikimedia CommonsA bust of emperor Commodus wearing a helmet made of lion hide.

Other emperors went further still. Septimus Severus, who ruled from 193 A.D. until 211 A.D. tried to outdo his predecessors by constructing a giant ship in 204 A.D. — probably in Circus Maximux — which broke apart to release bears, lions, leopards, ostriches, donkeys, and bison.

The emperor Probus (276 to 282 A.D.) arranged a similar venatio. Probus ordered the floor of Circus Maximus to be covered with bushes and trees to make it look like an overgrown forest.

He then released a variety of exotic creatures into the shrubbery and invited the audience to come down from their seats and join the hunt. Whatever creature they caught, they were apparently allowed to take home and eat.

Once that was done, Probus moved the celebration to the Colosseum, where hundreds of lions were exhibited, hunted, and killed.

The End Of Ancient Rome’s Staged Hunts

Wikimedia CommonsA mosaic from the 3rd-century depicting wild animals killed during a staged hunt.

By the third and fourth centuries, the popularity of ancient Rome’s venationes had begun to decline. This came about for several reasons.

One, the stars of the show — the exotic animals themselves — were getting harder to find. The celebration for the millennium of Rome in 248 A.D. included a “mere” 32 elephants, 10 elks, 10 tigers, 60 tame lions, 30 tame leopards, 10 hyenas, 6 hippos, 10 giraffes, and one rhino. Although this is an impressive number, more than enough to fill a modern-day zoo, it pales in comparison to the thousands of animals that once satiated Rome’s appetite.

Rome no longer had the finances or the military might to draw exotic animals from every corner of its empire.

In addition, social mores were changing. The Christian church had begun to exert more influence in Rome. In 404 A.D., a monk named Telemachus leaped into the ring to stop some gladiators from fighting each other. He was killed, and the emperor Honorius subsequently banned future gladiator matches.

Romans continued to make animals fight in venationes for a while afterward, but the insatiable bloodlust that had surrounded the first few centuries of games had abated. No longer did Romans have the appetite — or the budget — to slaughter thousands of animals over 100 days.

However, venationes were held until around the seventh century. And archeologists have uncovered scenes of hunts on mosaics, ceramics, silverware, and other objects, proving that the subject remained popular among Romans.

By the time the era of venationes was over, the Romans had forever altered the ecosphere of the entire region under their control, from North Africa to the Middle East to the Mediterranean coast of Europe. They slaughtered scores of animals into extinction or near-extinction while turning vast swathes of land into veritable deserts.

Among the animals that the Romans either wiped out or almost wiped out are the European wild horse, the Eurasian lynx, the North African elephant, the Barbary lion, and many others.

In the end, the Romans caused the greatest mass dying since the Pleistocene megafauna extinction that killed off the likes of the mammoth and the mastodon.

Meanwhile, the Romans’ rapid territorial expansion coupled with ecologically irresponsible farming practices meant that entire swathes of land went from fertile and verdant to dry and desolate. Mass deforestation and plundering of natural resources left areas like Sicily and much of North Africa relatively barren in ways that persist to this day.

Today, the very idea of venationes feels unimaginable. But their appeal endures. In the last century, modern-day humans have enjoyed visiting elephants at zoos, watching bears perform during the circus, and seeing whales put on a show at Seaworld.

That’s not the same as watching a bear kill a lion or a venatore spear a leopard. But it does say something about mankind’s fascination with exotic beasts.

After reading about the bloody staged hunts that took place in ancient Rome, learn about Captain Jack Bonavita, the fearless lion trainer in the 20th-century. Or, see how some Christian martyrs met brutal ends.