First described by neurologist Constantin von Economo in 1917, encephalitis lethargica infected more than 1 million people — and killed an estimated 500,000.

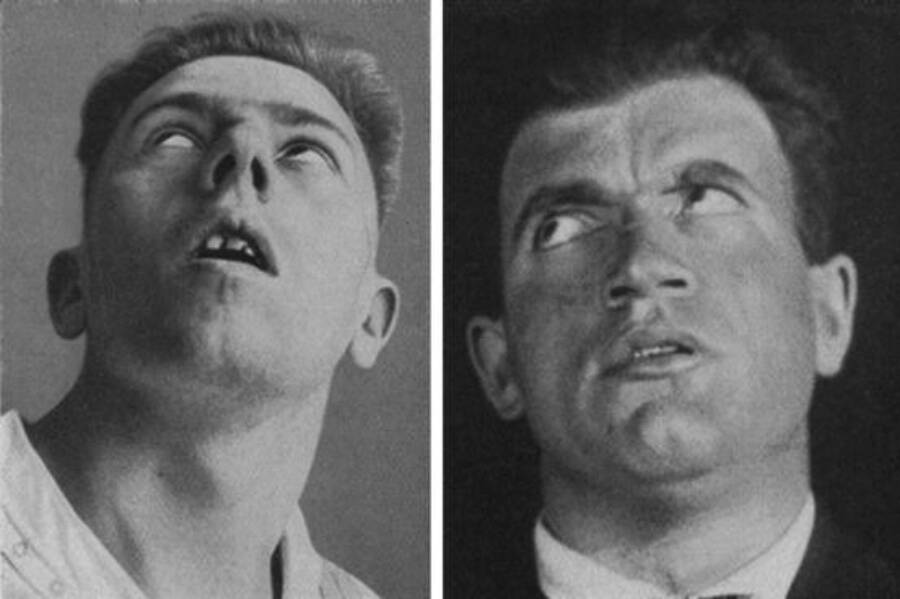

Paul Bernard FoleyPatients with encephalitis lethargica, also known as “sleeping sickness” or “sleepy sickness.”

Between the mid-1910s and the 1930s, an epidemic of encephalitis lethargica (EL) spread around the world, affecting more than 1 million people and leading to an estimated 500,000 deaths.

The mysterious neurological disease baffled physicians, as those who were infected experienced a wide variety of symptoms, including extreme tiredness, sleep disturbances, fevers, headaches, muscle pains, vision issues, psychiatric changes, and sometimes even symptoms resembling Parkinson’s disease. While many victims died of respiratory failure soon after being infected, some survivors suffered a far worse fate.

Some people who contracted EL eventually developed severe neurological disorders, like post-encephalitic Parkinsonism, and in the most extreme cases, victims were left with an immobile face, rigid muscles, and an inability to interact normally with other people. This left them in an almost statue-like state or puppet-like state — with their minds still active.

Given that the spread of encephalitis lethargica happened around the same time as the Spanish flu pandemic, researchers initially believed that there may have been a link between the two conditions, but this was never conclusively proven. The exact cause of EL remains unknown to this day.

Even more strangely, the disease seems to have vanished just as mysteriously as it appeared, barring a handful of isolated cases.

The Emergence Of Encephalitis Lethargica

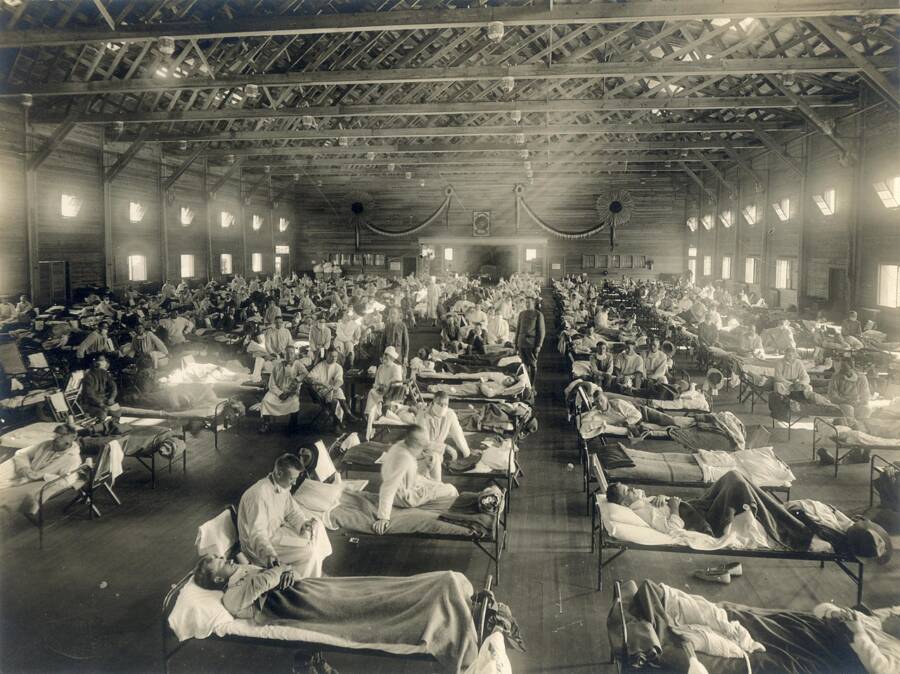

Public DomainPatients being treated for the Spanish flu at Camp Funston in Kansas. Circa 1918.

The sudden emergence of EL was one of the biggest medical mysteries of the early 20th century. Some of the first cases began cropping up as early as 1916 (or perhaps even 1915), but it wasn’t until 1917 that the Austrian neurologist Constantin von Economo identified a unique pattern of symptoms among patients in Vienna. Around the same time, French physician Jean-René Cruchet reported similar cases in France.

Despite the similarities with the symptoms, however, no one could find a definitive common cause or method of transmission.

Of course, the world was still in the throes of World War I at the time. And then, in the postwar period, even more death followed.

In 1918, the H1N1 influenza known as the Spanish flu rapidly spread across the planet and affected over one-fourth of the global population. When cases of EL were appearing at the same time, it was a natural assumption that it was perhaps some horrendous side effect of the flu. But there was never any direct link established between EL and the Spanish flu virus.

Trying to find a cause was made even more complicated, as Dr. Heidi Moawad noted in NeurologyLive, since not all patients had the same symptoms or the same level of severity with their symptoms.

“According to the medical literature, about a third of the patients died from respiratory failure caused by neurological dysfunction,” Moawad explained. “And, while at least hundreds [of] thousands of patients died, there were at least as many who survived. Some of the survivors exhibited residual Parkinsonian or neuropsychiatric sequelae.”

Because of this, a potential connection between Parkinson’s and EL was likewise explored, yet once again there was no definitive link. Others theorized that EL was caused by an autoimmune condition or streptococcal infection, but the disease’s true origins still haven’t been discovered.

Environmental and societal factors such as World War I, crowded living spaces, and global travel may have facilitated the spread of the disease, but these factors still would have only influenced the likeliness of infection rather than revealed the actual origin of encephalitis lethargica.

Uncovering The Mysterious “Sleeping Sickness”

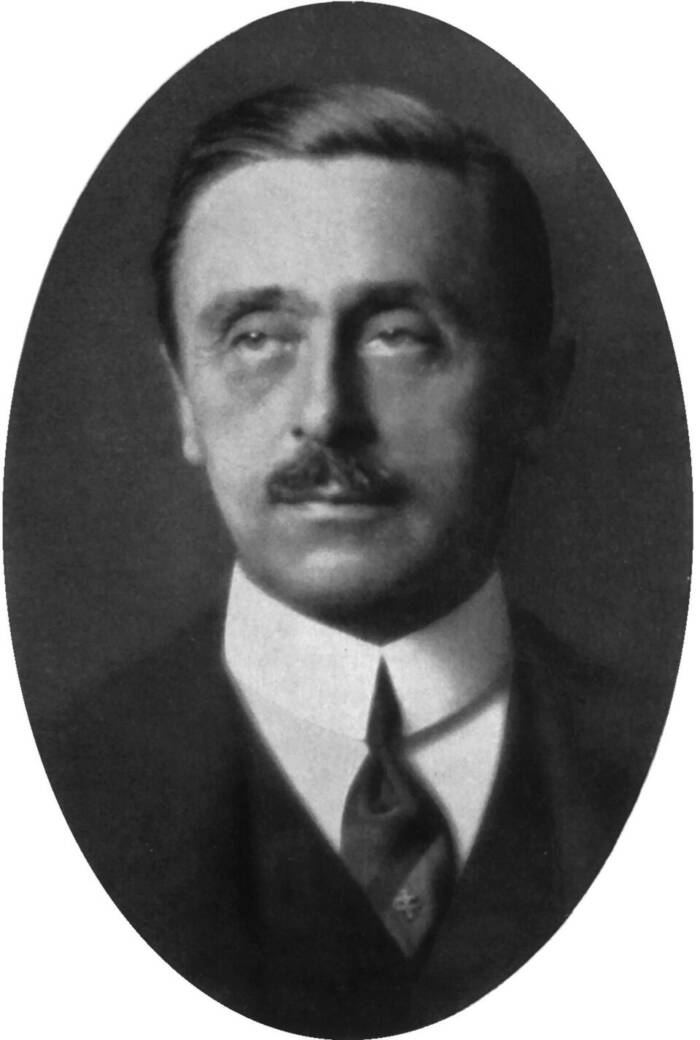

Public DomainConstantin von Economo, the man who identified EL.

Dr. Constantin von Economo of the Psychiatric-Neurological Clinic of the University of Vienna examined patients in late 1916 who had been presenting odd neurological symptoms. According to an Oxford Academic article by Leslie A. Hoffman and Joel A. Vilensky, those patients had been admitted with diagnoses ranging from meningitis to multiple sclerosis to delirium.

However, none of the diagnoses truly aligned with any known diagnostic scheme — and the presence of notable lethargy among each patient suggested a common affliction that didn’t seem to fit a known illness. Von Economo believed that this required the description of a new disease, which he outlined in a 1917 manuscript titled Encephalitis Lethargica.

Another physician, Jean-René Cruchet, had been treating similar cases in France in a military hospital and published his own description of the disease around the same time as von Economo. Researchers eventually found that EL presented itself in two phases, one acute and one chronic.

Researcher Paul Foley summarized the stages (and added a third stage) in The Conversation, explaining that in the first phase, patients experienced general unease, double vision, extreme drowsiness, and sometimes a fever.

“The second phase was marked by a general loss of concentration and interest in life, giving a vague sensation that the patient was not the person they had once been,” Foley wrote. “But this period, which resembled chronic fatigue syndrome, was the calm before the storm.”

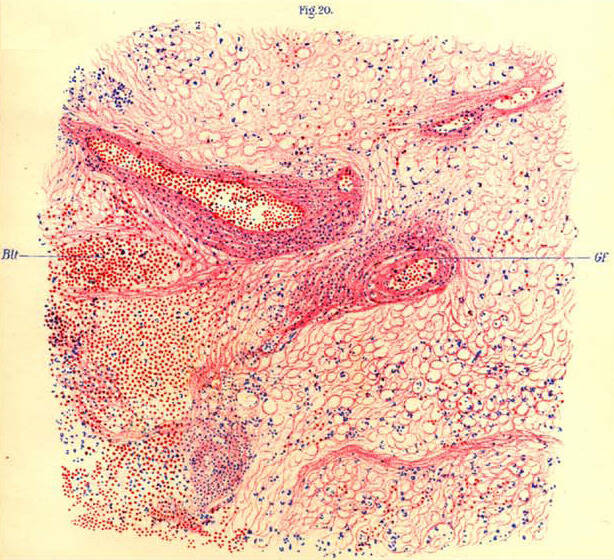

Public DomainAn illustration by Constantin von Economo, showing the brain tissue of a monkey with encephalitis lethargica.

After some time — which could have been anywhere between a few days and decades — some patients developed post-encephalitic parkinsonism (PEP), a potential third phase of the disease. It was an irreversible condition that effectively disabled sufferers for the rest of their lives.

Some patients contracted encephalitis lethargica as children. If they were infected between ages 5 and 10, they might eventually experience “pathologic changes of character that approached the psychopathic.”

At first, this may have looked somewhat like attention deficit disorders: restlessness, an inability to focus, clinginess, and so on. But as these children grew older, their impulsive behaviors could potentially lead to violent outbursts that posed a serious threat to themselves and others.

“Errant behaviours included cruelty to anyone who crossed them; destructiveness; lying; and self-mutilation including, in one example, removal of eyes,” Paul Foley explained. “When they reached adolescence, these patients manifested inappropriate and excessive sexuality, including sexual assault without regard for age or gender.”

More curiously, these dangerous behaviors were seemingly done purely out of impulse rather than selfishness. Patients often showed genuine remorse for what they had done and said that they had simply felt compelled to behave in the way they did. Unfortunately, some of them continued to let that impulse drive them well into adulthood, only to eventually fall victim to the Parkinsonism that put them in the statue-like state that came to characterize the most severe forms of encephalitis lethargica.

Eventually, these severely affected patients lost all willpower and sense of emotional connection. Music no longer moved them, even if they could recognize a musician’s skill. Despite some feeling empathy, they could no longer properly express sympathy. Their minds remained active, but they were incapable of normally interacting with the world as they once had.

For a while, it may have seemed like countless people would be doomed to suffer this terrible fate. But then, as suddenly as it had swept across the globe, encephalitis lethargica started to vanish.

What Happened To Encephalitis Lethargica?

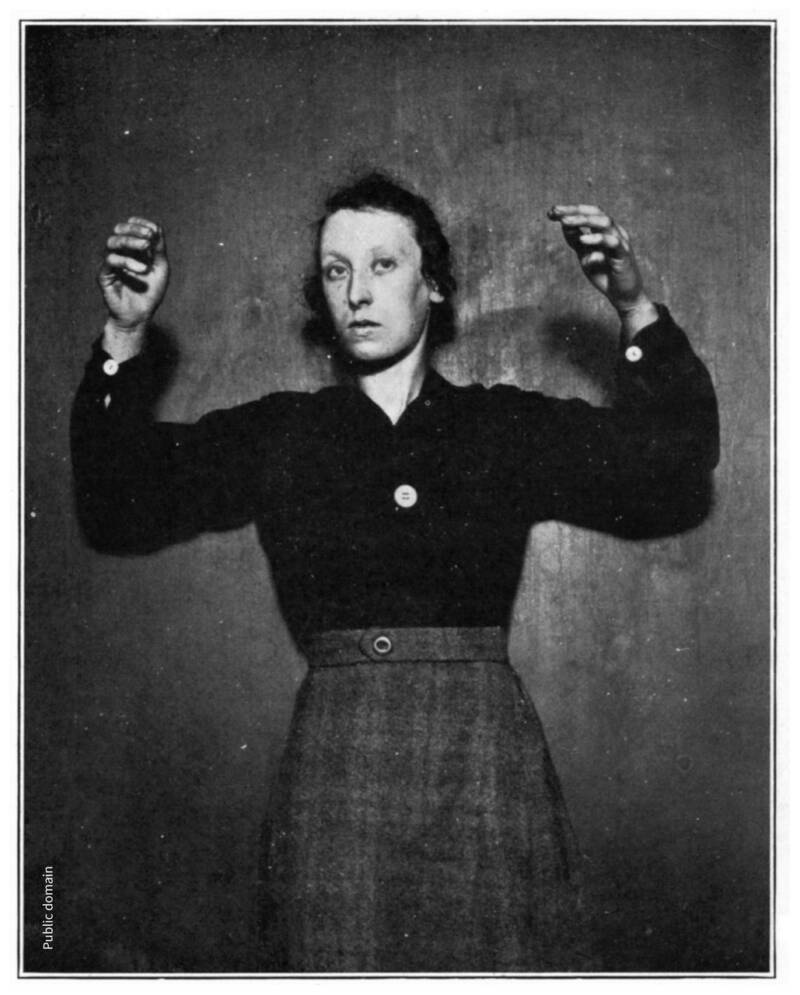

Public DomainA woman suffering from EL is stuck holding her arms in the air.

The EL epidemic reached its peaks during the early 1920s, but by 1927, cases had started to dwindle. According to the Oxford Academic article, a report in 1929 listed around 80 treatments for EL that had been attempted during the epidemic, none of which proved to be particularly effective.

In that specific report, one-third of patients who contracted EL died during the acute phase, one-third survived without any further complications, and the final third fell victim to later neurological decline.

But since 1940, there have only been around 80 published reports of EL worldwide. There have been some mild successes in treatments — namely with the Parkinson’s medication Levodopa (or L-DOPA), which was mentioned in British neurologist Oliver Sacks’ famous book Awakenings. The book later inspired a 1990 movie starring Robert De Niro as a patient recovering from the effects of the disease after decades of being in a shut-down state and Robin Williams as the doctor who was helping him.

Columbia PicturesRobert De Niro and Robin Williams in the 1990 movie Awakenings.

Sacks described the most severely affected EL patients as “extinct volcanoes” that “erupted into life” thanks to L-DOPA, but it turned out that his celebration was presumptuous. What actually happened was that L-DOPA only managed to help EL patients for a period of several months, after which they experienced adverse effects like tics and emotional instability.

More recently, some doctors have suggested that electroconvulsive therapy could prove effective for some patients, but with limited data to go on and mixed results, it can’t be said to be a cure. Even now, more than a century after it first emerged, there is no cure for encephalitis lethargica. Nor can anyone explain why the disease appeared and faded away like it did.

To this day, the EL epidemic remains one of the biggest medical mysteries of the 20th century. And some fear it could possibly return someday.

After reading about encephalitis lethargica, dive into the history of the Black Plague. Then, learn about some other devastating pandemics from history.