The 1918 Spanish flu pandemic, the deadliest of its kind in history, affected one in four people worldwide and claimed 50 million lives.

The unprecedented carnage of World War I accounted for some 20 million deaths between 1914 and 1918, leaving the world in a state of shock unlike anything seen before. But as the war was ending, another global cataclysm was underway. And though the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918 may not be as widely known, it killed perhaps three times the amount of people that the Great War ever did.

The H1N1 influenza known as the Spanish flu swept the globe throughout 1918 and ultimately affected more than one-fourth of the world's population. It spread to the farthest reaches of the planet — from the Arctic to the remote islands of the Pacific — and claimed upwards of 50 million lives worldwide (though some say as many as 100 million).

By the time the worst of it ended in late 1918, it was the worst outbreak of its kind in human history. Nevertheless, experts still aren't clear on exactly why the Spanish flu was especially deadly or even where it first started.

What we do know is that World War I only exacerbated the spread and mortality of the disease, though world leaders tried to downplay the flu's effects in their own countries in order to not seem weak during wartime. But after the war ended and in the decades since, the true history that came to light about the Spanish flu pandemic indeed showed what a historic tragedy it truly was.

"Death Was There All The Time": The Spanish Flu Sweeps The Globe

Wikimedia CommonsMen bury victims of the Spanish flu in Labrador, Canada in 1918.

Despite the scores of studies that attempted to make sense of the 1918 flu pandemic after the fact, experts were never able to determine for certain where it started.

One prominent theory is that it began at a British army base in France, while another — albeit disputed — theory is that it started in northern China and was carried to Europe by Chinese laborers. Yet another noteworthy theory is that it originated in Kansas, where some of the first cases were noted in very early 1918.

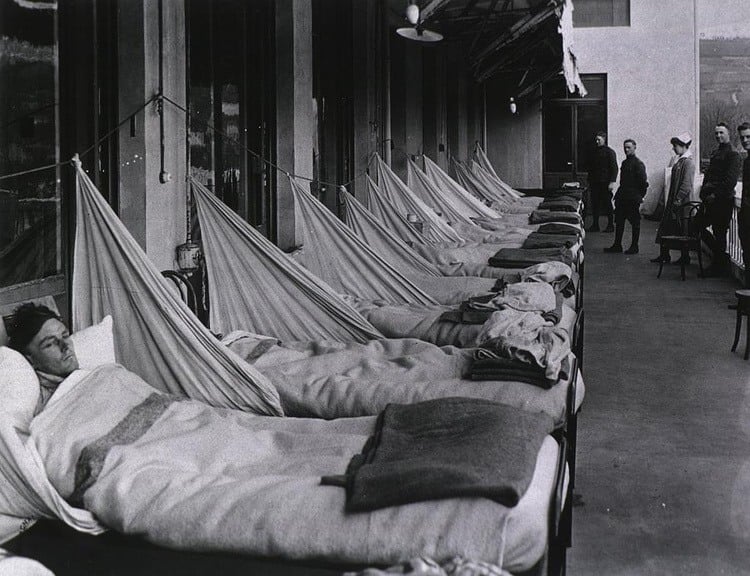

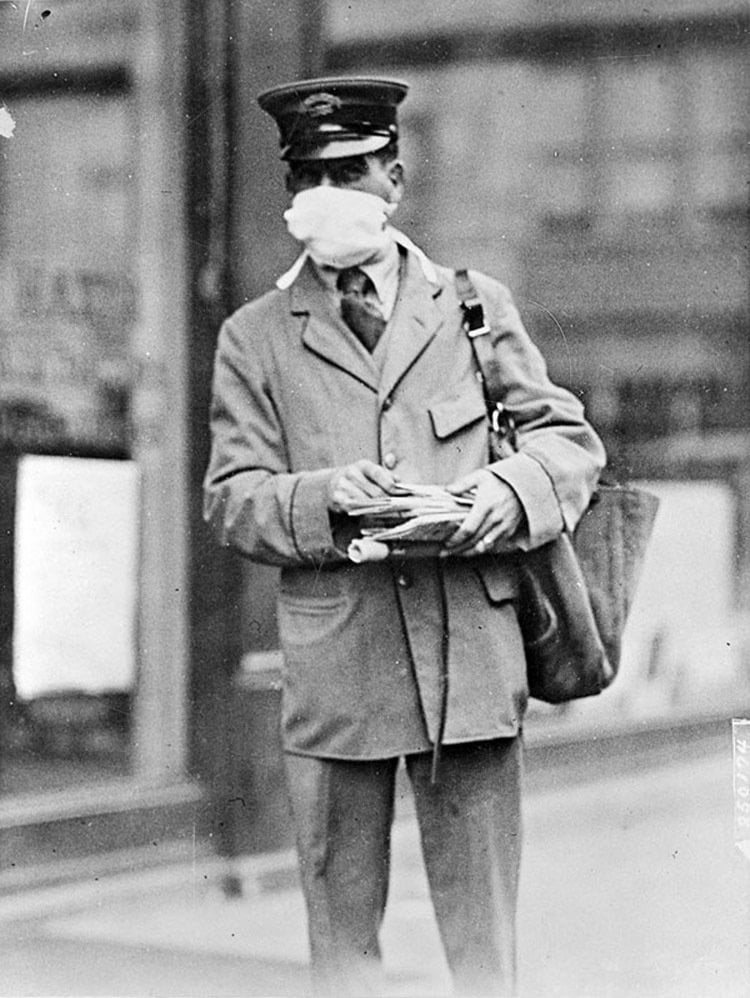

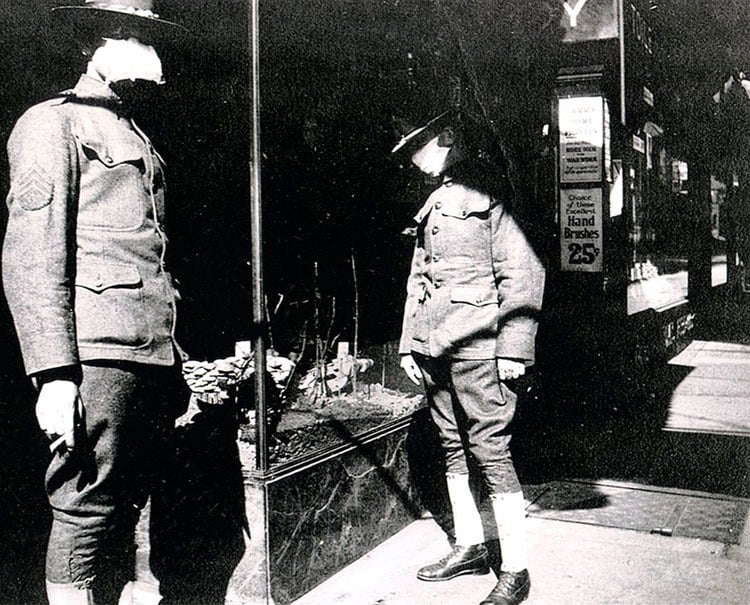

Regardless of where it started, the Spanish flu spread quickly starting in the winter of 1918. With many of the early outbreak points being military bases, troops carried the disease across the Atlantic and throughout Europe as armies were deployed for World War I.

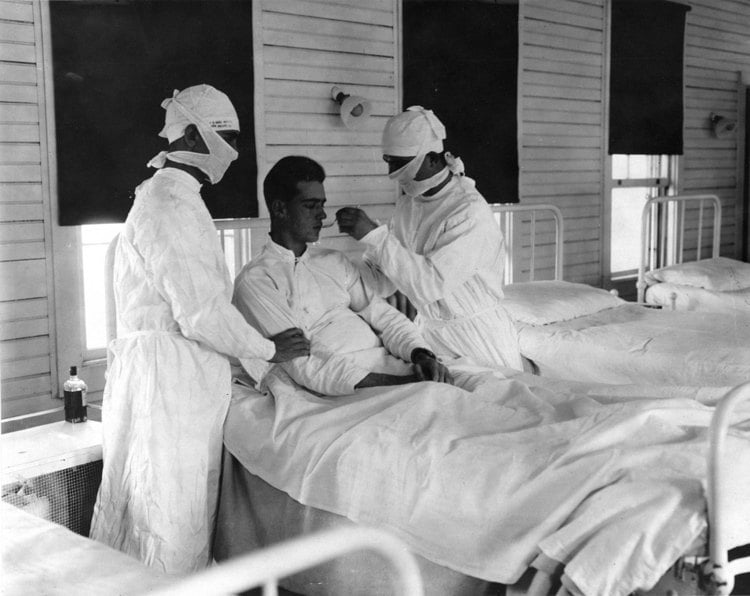

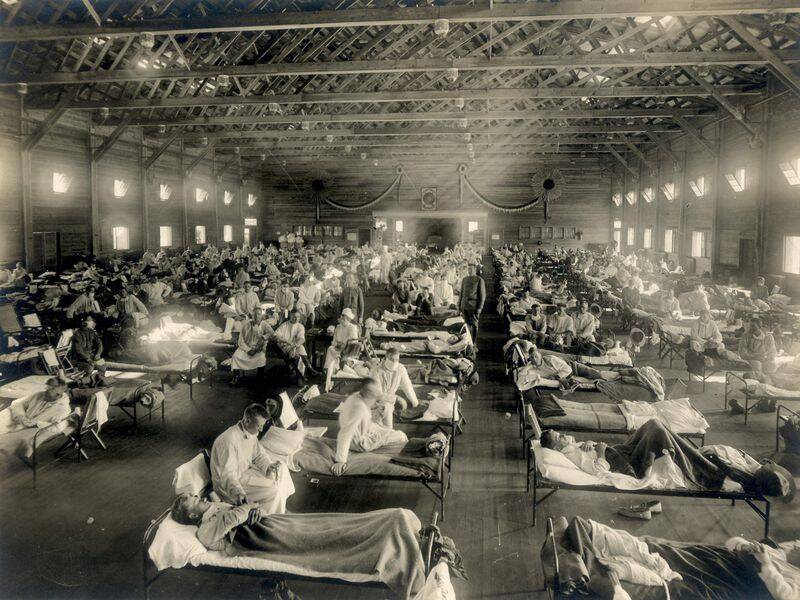

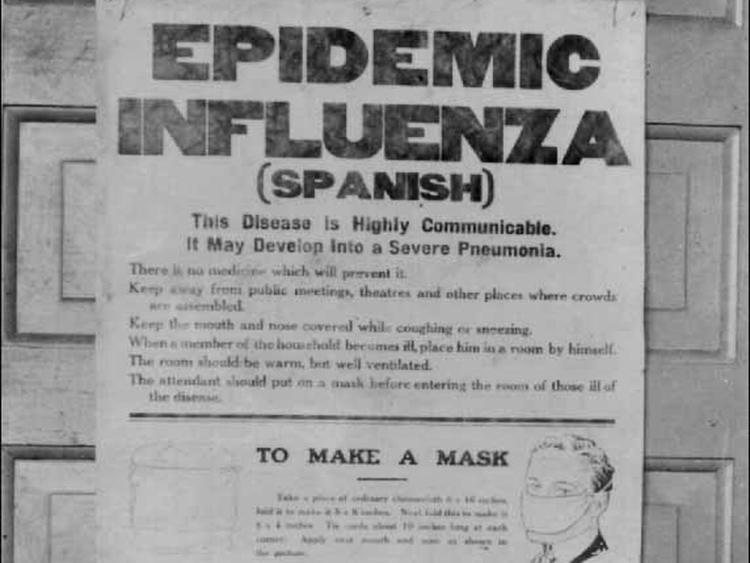

Troop movements, new modes of transportation (automobiles and planes, for starters), and easy transmission via coughing and sneezing allowed the Spanish flu to spread with ease. And once you were infected, you could experience standard flu symptoms like fever and aches — but perhaps also a deadly form of pneumonia in which the patient's "lungs filled with bloody fluid. They choked on the pinkish froth as they gasped for their last breath."

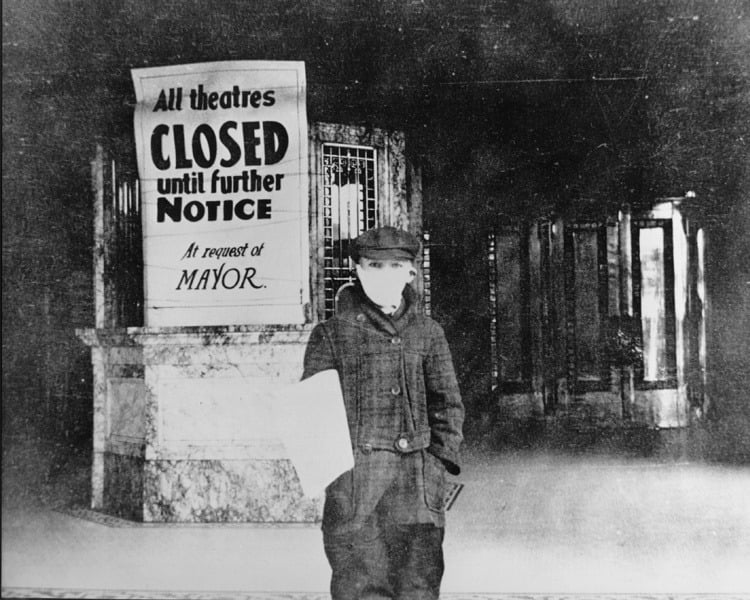

But these horrors were largely kept under wraps by most governments around the world who were not eager to show any signs of weakness during World War I. However, neutral Spain reported on their cases, hence the nickname Spanish flu.

Despite the relative lack of official reporting, the disease traveled around the world, leaving almost no area untouched. Things only grew worse in the fall of 1918 thanks to a second wave of the virus fueled by a new mutation that was deadlier than the first, making October and November the deadliest months of the entire 1918 pandemic. In the United States alone, the Spanish flu was so deadly that life expectancy dropped 12 years from 51 to 39 just for 1918.

"It was scary," survivor Kenneth Crotty, who was 11 and living in Massachusetts (one of the hardest hit areas), told CNN in 2005, "because every morning when you got up, you asked, 'Who died during the night?' You know death was there all the time."

In the end, death rates were about 2.5 percent and a total of 50 million are believed to have died.

The Aftermath Of The 1918 Flu Epidemic

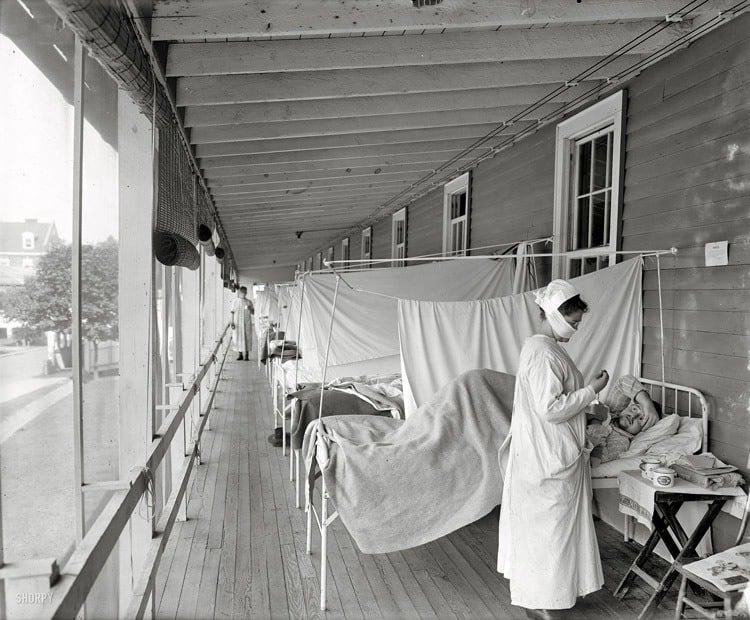

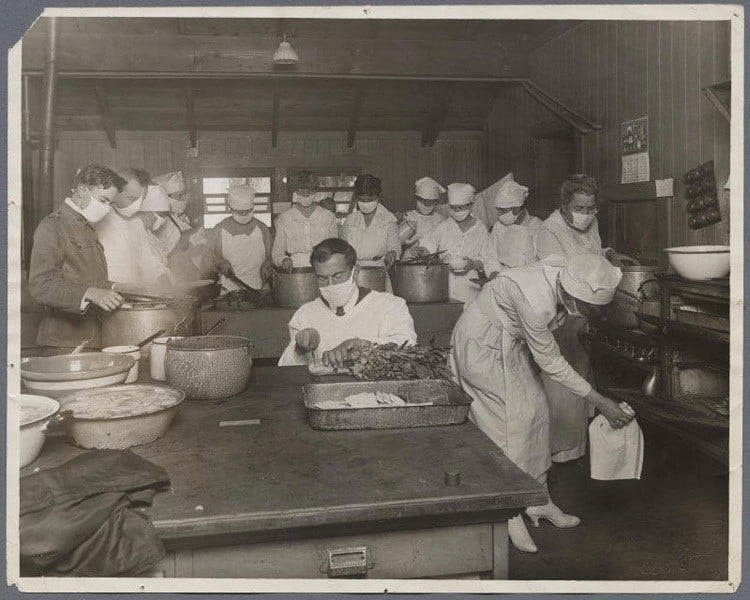

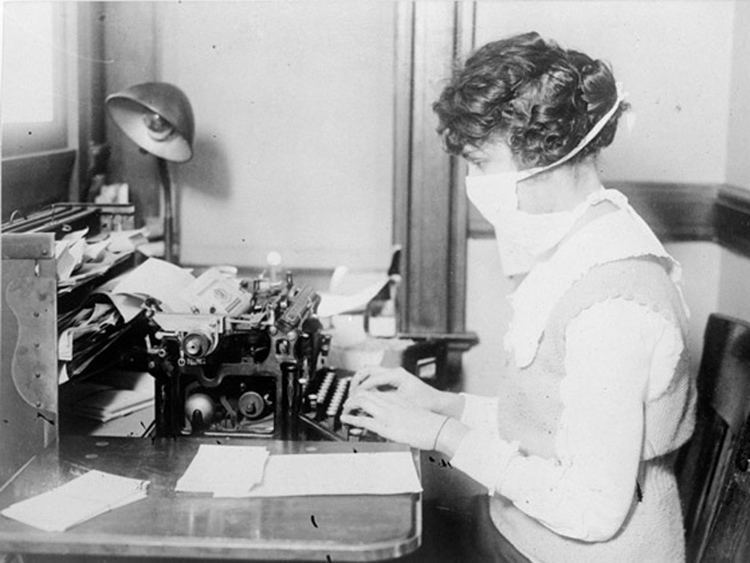

Wikimedia CommonsRed Cross workers on the job in Washington, D.C. during the Spanish flu epidemic of 1918.

The 1918 flu pandemic peaked with the second wave in the late fall but then calmed quickly afterward. Just as researchers have little idea of how it started, they have equally little idea for certain of how it ended.

Some say it was the end of the war, a fortunate mutation in the disease, increased abilities to provide treatment, natural development of immunity across populations, or some combination of the above.

By the summer of 1919, the Spanish flu pandemic had all but ended. And yet, there was no immediate, successful push to learn about why the illness was so deadly, or why it traveled the way that it did. In fact, in certain respects, interest in combating the flu ended as soon as the pandemic did.

Some, including the United States Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), say it had to do with the event's timing. "It is possible, that the pandemic's close association with World War I may have caused this amnesia," HHS wrote. "While more people died from the pandemic than from World War I, the war had lasted longer than the pandemic and caused greater and more immediate changes in American society."

It would take nearly a century before researchers developed an explanation for the 1918 flu's spread: Three genes were able to weaken the victim's respiratory systems — particularly the bronchial tubes and lungs — and allow pneumonia to take hold.

Ultimately, from its origins to its merciful end, the Spanish flu remains largely mysterious.

After this look at the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918, read up on other devastating pandemics from history. Then, read up on the disturbing symptoms of the Black Death.