In the 1930s, an Irish politician named Eoin O'Duffy embraced fascism and tried to turn Ireland into a dictatorship — but he ultimately failed.

Wikimedia Commons/Narodowe Archiwum CyfroweEoin O’Duffy as the commissioner of the Garda Síochána, the police force of the Republic of Ireland. He held this position for most of the 1920s and early 1930s.

In the years leading up to World War II, a disturbing number of countries around the world descended into fascism. And if Eoin O’Duffy had his way, Ireland would have been among them.

Once a respected leader of the Irish Republican Army, O’Duffy’s career took a disturbing turn when he embraced fascism in the 1930s. Idolizing the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini, O’Duffy hoped to one day have as much power as the Duce. Although he ultimately failed in his mission, he did help found one of Ireland’s most prominent political parties — which still exists today.

This is the little-known story of a man who dreamed of transforming Ireland into an imitation of Fascist Italy.

The Early Life Of Eoin O’Duffy

Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty ImagesIn 1933, Eoin O’Duffy was chosen to lead the Army Comrades Association, which he would rename the National Guard.

Eoin O’Duffy was born in a small rural community in County Monaghan, Ulster, near today’s border with Northern Ireland, in 1890. At the time, the whole of Ireland was part of the United Kingdom, and a nationalist sentiment had been steadily increasing there in the face of political repression.

In November 1917, O’Duffy left a comfortable civil service job to join the Irish independence movement, seeing great success as an organizer for the nascent Irish Army. He was even hailed as “the best man by far in Ulster.”

After the Irish War of Independence, O’Duffy was asked to take charge of the Garda Síochána — Ireland’s new national police force — in 1922.

The Garda had been plagued by indiscipline and ineffectiveness for months, and the government in Dublin turned to the charismatic O’Duffy to re-shape the police into a reliable force, which he did by advocating temperance and traditional Catholicism. He served as commissioner until 1933 — when he was dismissed by government leader Éamon de Valera.

O’Duffy had long been paranoid that de Valera was a Communist, and he had once considered staging a coup d’état to remove him from power. At one point, he even identified some supporters who would’ve helped him.

Ultimately, he didn’t go through with the act, but he didn’t do a good job of hiding his intentions. And when de Valera learned about O’Duffy’s suspicious behavior — like inviting high-ranking government officials to back him — O’Duffy was ejected from the force he’d rebuilt from the ground up.

Becoming The Leader Of The Blueshirts

Wikimedia Commons/Narodowe Archiwum CyfroweO’Duffy (center) adopted the trappings of fascism for the Blueshirts, turning them into an imitation of Mussolini’s Blackshirts and Hitler’s Brownshirts.

Although O’Duffy’s contempt for leaders in the Irish government had led to his dismissal, his reputation for efficiency and organizing won him widespread admiration among many ordinary Irish people.

Rather than fade into obscurity, he made his voice louder than ever before. And during the summer of 1933, he received an offer that changed his life.

He was invited to lead the Army Comrades Association (ACA), an organization ostensibly dedicated to honoring veterans of the independence war and guarding “the people and every threat to their freedom.”

Despite its military associations, the group was hampered by inefficiency and crippled by fighting with the Irish Republican Army (IRA). It was in desperate need of the skills of a leader like O’Duffy. Taking charge of the group in July 1933, O’Duffy quickly transformed the ACA into a reflection of his own personal beliefs. He started by giving it a new name: National Guard.

Already an admirer of Mussolini, O’Duffy clearly kept his idol’s practices top of mind. He ordered his followers to wear blue uniforms based on those worn by Mussolini’s Blackshirts. Never one for subtlety, his organization would soon become better known by the nickname “Blueshirts.”

Perhaps most alarming, he forced his men to greet him with fascist salutes and cries of “Hoch O’Duffy!” — a direct imitation of “Heil Hitler!”

Founding A New Party

Wikimedia Commons/Narodowe Archiwum CyfroweO’Duffy, rear, is seen leaving Dublin’s Arbour Hill Prison after visiting imprisoned Blueshirts in 1933.

Things came to a head in August 1933 when — mimicking the mass gatherings of fascist Italy and Germany — O’Duffy planned a thousands-strong Blueshirt parade. This would later be seen as a reflection of Mussolini’s “March on Rome,” which initiated fascist rule in Italy.

Given O’Duffy’s coup plot and his open admiration of dictatorship, the Irish government took steps to make sure that this march wouldn’t happen, like crowding Dublin with police. Though O’Duffy eventually canceled the march, the government soon banned his organization completely.

It’s doubtful whether the “March on Dublin” was intended to be a coup, but the government’s ban forced O’Duffy out of a position of power once more. As he maniacally claimed that his followers would “be tried under martial law conditions,” O’Duffy was clearly desperate to salvage his group.

Surprisingly, that salvation came just days after the official ban of the Blueshirts. O’Duffy’s party was invited to band together with two other conservative factions to create Fine Gael. Ironically, because O’Duffy hadn’t yet directly embraced fascism, he was chosen to lead it. He then relinquished control of the Blueshirts to his underling Ned Cronin.

But the continued existence of the Blueshirts proved to be O’Duffy’s political undoing. While the group operated under new names — like Young Ireland Association — the members weren’t fooling anyone. And for much of 1934, they staged attacks on IRA members, policemen, and anyone else who opposed them, creating an atmosphere of terror and violence.

The financial and political costs of funding the Blueshirts eventually resulted in O’Duffy becoming an embarrassment for the Fine Gael leadership. By September 1934, Eoin O’Duffy decided to leave the party he’d helped create, cutting off any path to power he might’ve had through electoral means.

O’Duffy’s Descent Into Fascism

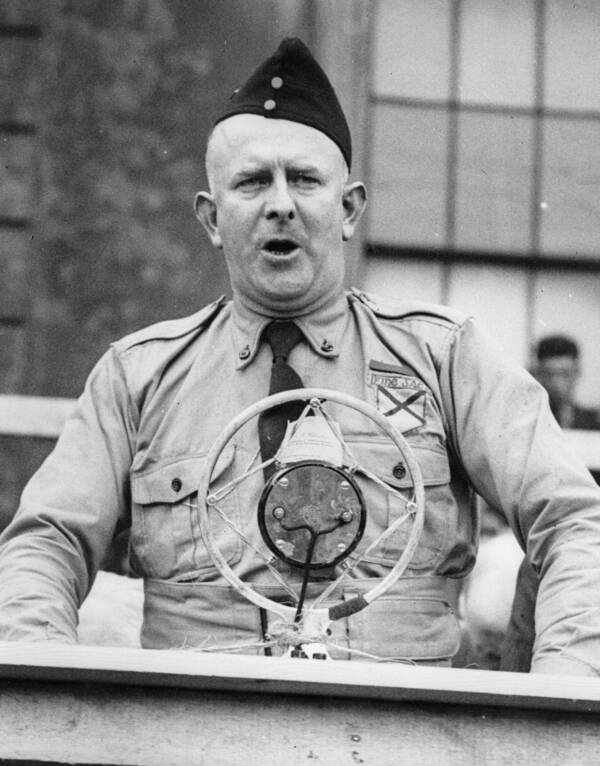

Keystone/Getty ImagesEoin O’Duffy speaks to supporters in 1934. While he had a large following, he never gained the power he desired.

Eoin O’Duffy had long since adopted fascism as his personal ideology in private. But after he left Fine Gael, he set about making that adoption public.

Embarking on a campaign to take back control of the Blueshirts, O’Duffy made his group the face of Irish fascism, even representing it at the 1934 international gathering of fascist parties in Montreux, Switzerland. There, he ludicrously described himself as “the third greatest man in Europe.”

In reality, the Blueshirts were far from being an admired group in Ireland — or anywhere else for that matter. And O’Duffy was the lonely leader of a widely-ridiculed faction at the edge of the continent.

But the start of the Spanish Civil War represented a change of luck. Senior Catholic clergymen and Spanish Nationalists encouraged O’Duffy to fight for Francisco Franco. Motivated by anti-Communism, pro-Catholicism, and his own self-interest, O’Duffy agreed. In 1936, he established the “Irish Brigade,” which consisted of 700 volunteers — many of whom had been Blueshirts.

Dressed in Spanish uniforms and armed with Spanish rifles, the Irish Brigade was poorly led, and its members soon earned a reputation for indiscipline and drunkenness. Eventually, they were deployed to take part late in the Battle of Jarama, but the only combat they saw was an exchange of friendly fire with another group of volunteers in a case of mistaken identity.

After months of lackluster performance, Franco no longer needed the Irish Brigade, whose only value had ever been for public relations. All but a handful of diehards voted to return to Ireland. They landed in Dublin in June 1937 and were greeted by spectators who glared at them in stony silence.

How Eoin O’Duffy Faded Into Obscurity

Wikimedia CommonsIn 1944, O’Duffy died at age 54. By that point, most of his political groups had crumbled.

Always eager to portray himself in the most favorable light, O’Duffy set out to prove that his time in Spain had been exemplary, publishing a book titled Crusade in Spain. Despite spending 200 pages attributing the failures of the Irish Brigade to others and giving himself credit for its imaginary successes, he failed to convince anyone. His reputation was at last permanently ruined.

Although he remained the public figurehead of Irish fascism, that movement’s waning popularity meant that he had little influence.

Sinking into alcoholism in spite of his lifelong teetotalism, O’Duffy was left behind by political life. Although he kept in touch with German fascists, praised the vile anti-Semitic broadcasts of Lord Haw-Haw, and constantly dreamed up ever more unrealistic political schemes, his lack of influence made him a worthless ally to the Nazis during World War II.

In 1943, he approached German representatives with an offer to help the Nazis on the Eastern Front. He was politely thanked and completely ignored.

Desperate for a way to remain in the public eye, O’Duffy took over the National Athletic and Cycling Association, advocating for the imprisonment of bicycle thieves. But his increasing alcoholism crippled his once-stellar organizational abilities. The police who monitored him reported that he “had no other interest in life but to get hold of brandy.”

His health ruined as he was completely forgotten by the public, Eoin O’Duffy died at age 54 on November 30, 1944, in Dublin.

To this day, O’Duffy remains one of the most controversial Irishmen in modern history. Some Fine Gael politicians still refuse to discuss the role he played in their party’s founding. And the most time-honored insult in Irish politics is to call a member of that party a Blueshirt.

Now that you’ve read about Eoin O’Duffy, take a look at Sir Oswald Mosley, his English counterpart who tried to turn Britain into a Nazi puppet state. Then, learn the shocking truth behind the death of Benito Mussolini.