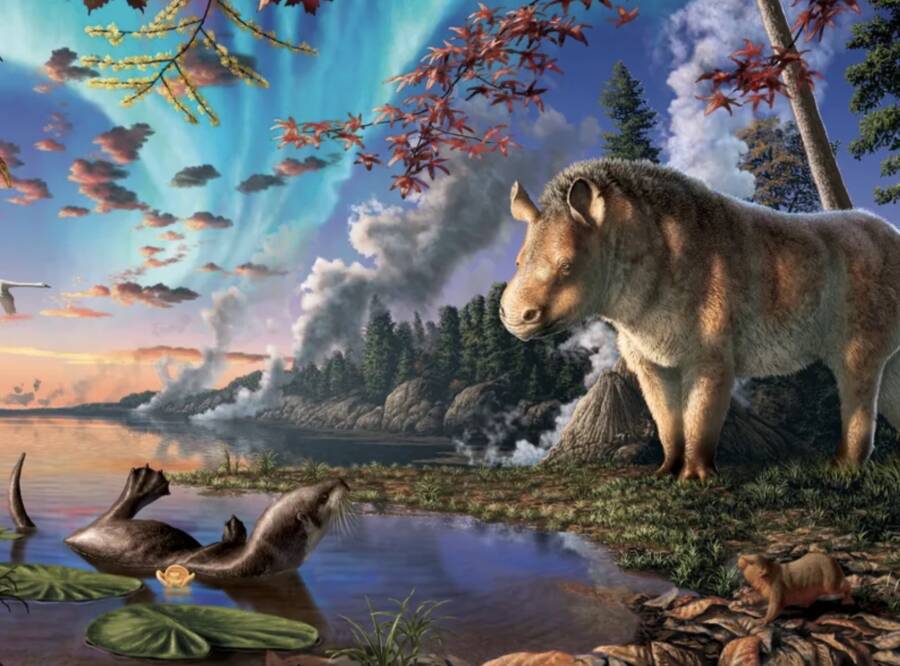

Due to its small, pony-sized body and horn-less skull, researchers were initially baffled as to what Epiaceratherium itjilik was, calling the creature "a little bit of a weirdo."

Julius CsotonyiResearchers in Canada have identified a new species they’re calling the “frosty rhino” that lived in the Arctic some 23 million years ago.

Scientists have discovered a new species of rhino that roamed the Canadian Arctic roughly 23 million years ago.

The polar rhino, or Epiaceratherium itjilik, was uncovered in Nunavut, Canada, about 600 miles above the Arctic Circle, making it the northernmost rhino ever discovered. The animal had no horns, and was relatively small compared to most of its modern brethren. It was, however, similar in size to the modern Indian rhino.

Researchers theorized that the rhino made its way to Canada from Europe using the North Atlantic Land Bridge, indicating that this land bridge existed for far longer than previously thought. This find also has the research team wondering what other astonishing Arctic animals from the prehistoric era have yet to be uncovered.

The Discovery Of A Prehistoric Arctic Rhino That’s Nothing Like Modern Species

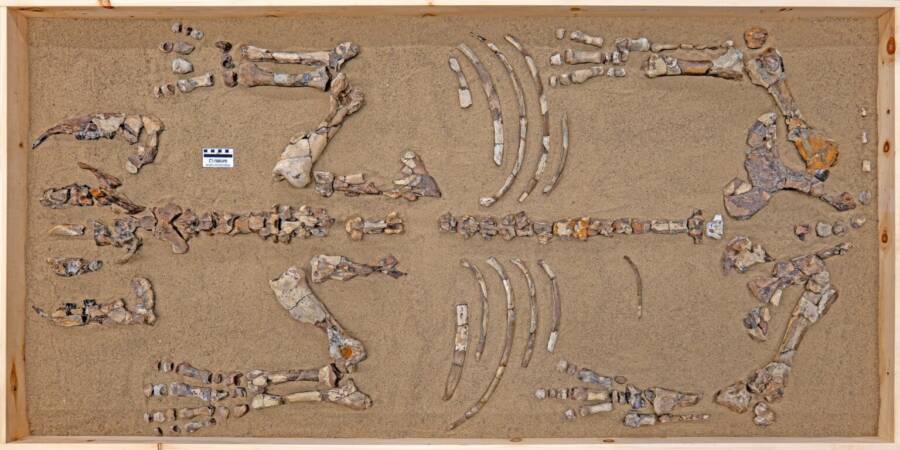

Pierre Poirier/Canadian Museum of NatureThe researchers were able to uncover 75 percent of the animal’s bones.

A new study published in Nature Ecology & Evolution describes what scientists currently know about the newly-discovered Epiaceratherium itjilik.

For one, instead of a large horn on its nose, the Arctic rhino had a narrow nose and mouth.

This was ideal for moving through leaves and branches on trees and shrubs to look for food. During the Early Miocene, when the animal was roaming the Arctic, the landscape looked much different than it does today. Instead of a desolate polar desert, the Canadian Arctic was filled with pine, larch, alder, spruce, and birch forests.

Another surprising characteristic is that, unlike modern rhinos — who have three toes on each foot — the E. itjilik had four toes on each of its feet. The rhino’s bones also revealed it was about three feet tall, approximately the size of a small pony.

Martin Lipman/Canadian Museum of NatureStudy authors Natalia Rybczyski and Mary Dawson looking over the bones of Epiaceratherium itjilik in 2007.

The new rhino’s name, “Itjilik,” means “frosty” in Inuktitut, one of the languages spoken by the Inuit people of northern Canada. The name was chosen through a collaboration with Jarloo Kiguktak, an Inuit elder and the former mayor of Grise Fiord.

While the E. itjilik was only recently confirmed as a new species, this find was decades in the making. The E. itjilik bones were first unearthed by late paleontologist and curator emeritus at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History Mary Dawson in 1986.

When she found the bones within the 14-mile-wide Haughton Crater, which was created by an asteroid impact more than 23 million years ago, Dawson immediately knew they came from a rhinoceros because of the distinctive bands on the teeth.

After consulting various rhino experts, no one could tell her what exactly the animal was. Scientists, including Dawson, continuously returned to the site throughout the 2000s, eventually excavating 75 percent of the creature’s bones. In the end, it took four decades to finally solve the mystery of these Arctic rhino bones.

“What’s remarkable about the Arctic rhino is that the fossil bones are in excellent condition,” study co-author Marisa Gilbert said in a statement from the Canadian Museum of Nature. “They are three dimensionally preserved and have only been partially replaced by minerals. About 75% of the skeleton was discovered, which is incredibly complete for a fossil.”

How Epiaceratherium itjilik Made Its Way To Canada

Martin Lipman/Canadian Museum of NatureResearchers examine the Arctic rhino’s bones.

Along with describing the rhino, the study also delves into one of the possible ways in which the E. itjilik came to make Canada its home. The researchers suggest that the animals may have made their way to the Americas via the North Atlantic Land Bridge from Europe.

Through extracting and analyzing the proteins in the rhino’s teeth, researchers concluded that the Arctic rhino is similar to species found in Europe, the Middle East, and southwestern Asia. Researchers believe that the rhino could have traveled from these regions to Canada using the land bridge.

However, this would mean that the North Atlantic Land Bridge existed for far longer than previously thought. It was initially believed that the land bridge disappeared during the early Eocene, roughly 30 million years before E. itjilik inhabited Canada. The researchers also suggested that it was possible that the land bridge had already broken up into islands by the time the rhino made its journey to Canada, making it still possible to cross.

However, this theory has not been universally accepted. A paleooceanographer who was not involved with the study, Philip Sexton, told the Globe and Mail that the theory “conflicts with all geological evidence.”

Regardless of how the animal got to Canada, the discovery of the Arctic rhino has inspired the researchers to think about what other unknown prehistoric animals once lived in this region.

“We often think about the tropics as centers for biodiversity—and they are,” lead author Danielle Fraser told Reuters. “But the more fossil discoveries we make in the Arctic, the more it is becoming clear that it was an essential region in the evolution of mammals.”

After reading about the newly discovered polar rhino, take a look at 11 unbelievable prehistoric animals. Then, learn about the prehistoric rhino heard discovered in Nebraska.