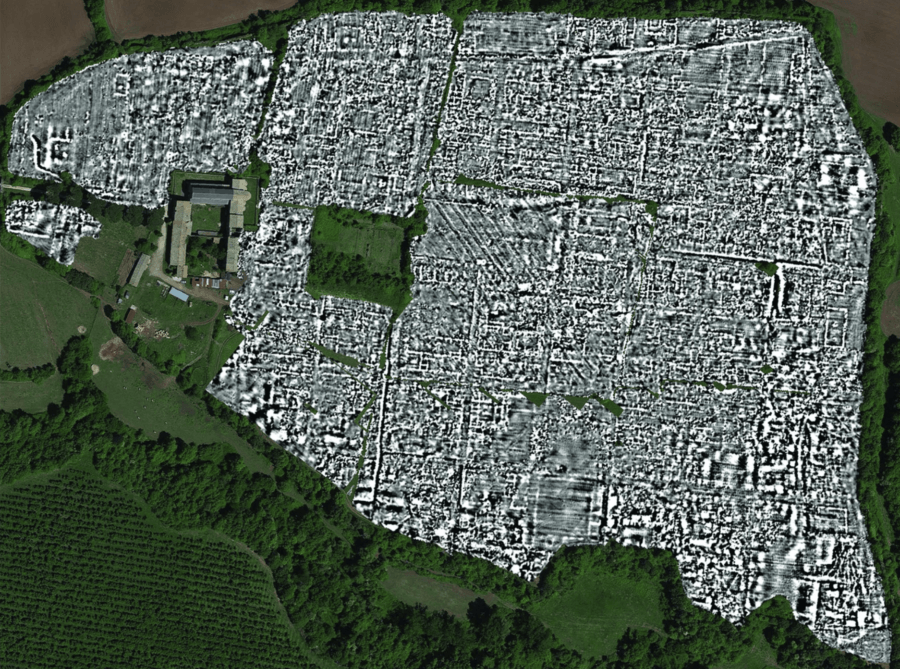

The city of Falerii Novi was abandoned in 700 A.D. and has been buried ever since.

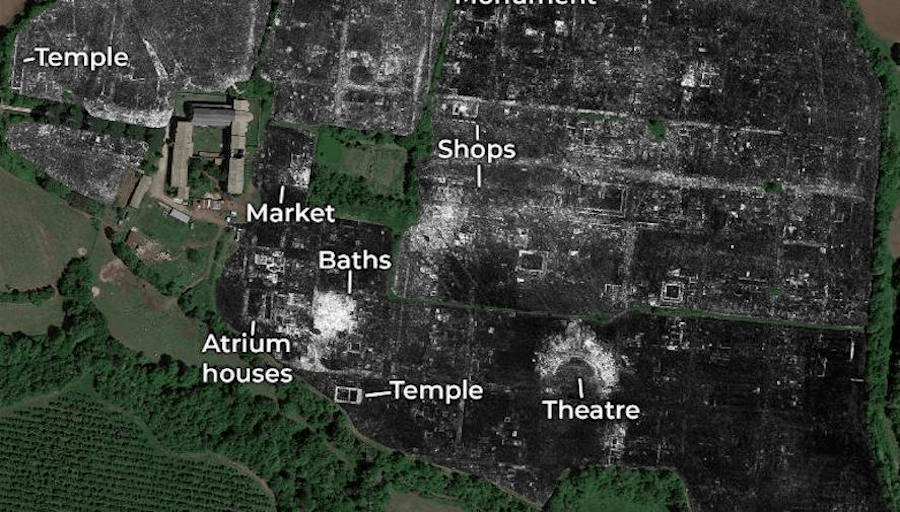

Verdonck et al., 2020/AntiquityFalerii Novi was populated by around 3,000 people and contained a theater, shops, and monuments.

For the first time in history, archaeologists have mapped an entire ancient Roman city using ground-penetrating radar. According to The Guardian, the buried town of Falerii Novi contained a bathhouse, theater, several temples and shops, and a large monument of a kind experts have never seen before.

Once a proud, 75-acre outpost 31 miles north of Rome, Falerii Novi was built and occupied in 241 B.C. and abandoned in 700 A.D. Though it’s been thoroughly buried over the course of time, new technology has allowed experts to see through layers of ground and map the town in detail without digging.

According to CNN, the uncovered public monument baffling experts is only one example of how this new approach could change the field of archaeology. Published in the Antiquity journal, the findings indicate this could merely be the first — in a long line of ancient cities — to be explored this way.

“The astonishing level of detail which we have achieved at Falerii Novi, and the surprising features that [ground-penetrating radar] has revealed, suggest that this type of survey could transform the way archaeologists investigate urban sites, as total entities,” said study author Martin Millett, who teaches classical archaeology at the University of Cambridge.

Verdonck et al., 2020/AntiquityResearchers have yet to analyze all the data they’ve captured — which they imagine will take up to a year.

A joint effort on behalf of the University of Cambridge and the University of Ghent, the scans uncovered a route along the outskirts of the city which Millett believes was likely used as a religious processional way.

For him, no kind of settlement is more informative than urban hubs like this when studying Ancient Rome.

“If you’re interested in the Roman Empire, cities are absolutely critical because that is how the Roman Empire worked — it ran everything through local cities,” he said. “Most of what we’ve got, apart from in sites like Pompeii, are little bits.”

“You can dig a trench and get little insights, but it’s very difficult to see how they work as a whole. What remote sensing does is enable us to look at very large, complete sites, and to see in detail the structure of those cities without digging a hole.”

Verdonck et al., 2020/AntiquityThe GPR took readings every five inches, and was towed by a quad bike.

Falerii Novi is around half as large as Pompeii. Fortunately, it hasn’t been built over, which made the scanning process rather easy. To do so, researchers simply towed a series of antennae over the ground by riding a quad bike across the site. This array of antennae took readings every five inches.

The approach is fairly similar to standard radar technology and essentially sends radio waves into the ground. By hitting and bouncing off objects and their surfaces, their echoes reveal how deep certain surfaces are compared to others — and thereby create a detailed, three-dimensional picture.

The water system’s construction revealed it was built before the structures atop were — instead of running along the grid of streets. This foresight in planning was enacted “in a way that’s familiar today, but not expected, I think, in the third century B.C.,” explained Millett.

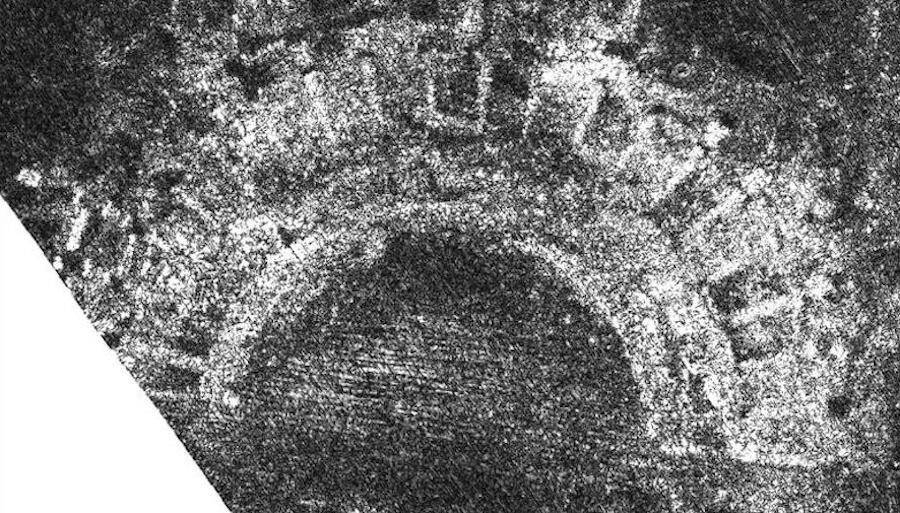

The public monument, meanwhile, was nearly 200 feet long and lined with colonnades. It contained two smaller structures with niches allowing for fountains and statues. Millett was naturally stunned at the find, and claimed “no one I’ve yet shown it to yet knows what it is.”

Verdonck et al., 2020/AntiquityThe ancient theater at Falerii Novi.

Though still mysteries in its function, Millett believes it likely stemmed from cultural and religious practices of the Faliscan people — those who occupied this region of Italy before it was conquered by Rome.

“One of the big areas of discussion about the Roman Empire is the way individual local communities worked, and how that interacted with the overall structures of Roman imperial power,” he said.

“What you’re seeing at Falerii, with this religious element to the landscape around the edge of the city, is probably the product of the local Faliscan identity. We’re seeing elements of their religious practice, we imagine, recreated within the Roman sphere.”

Though GPR isn’t particularly new — and has been used since the 1910s — the resolution is far higher and speed much quicker nowadays. Millett explained it’s not difficult, for instance, to detect a small, eight-inch column even if buried under six feet of soil.

Martin MillettFortunately, Falerii Novi wasn’t built over — making it rather easy to scan by driving across with a quad bike.

Of course, processing that data takes time. For every 2.5 acres scanned, about 20 hours of image processing are required. Millett and his peers haven’t even finished looking over all the data they’ve amassed, and are currently attempting to develop automated technology.

As it stands, a complete analysis of all captured imagery of Falerii Novi is expected within the next year. Millett and his team already have an admirable amount of experience with the method, having scanned buried locations in Italy and England — and are already looking ahead at future prospects.

“It is exciting and now realistic to imagine GPR being used to survey a major city such as Miletus in Turkey, Nicopolis in Greece or Cyrene in Libya,” he said. “We still have so much to learn about Roman urban life and this technology should open up unprecedented opportunities for decades to come.”

The potential for a clearer understanding of history by way of this seemingly convenient technology is certainly astonishing. With archaeological teams across the world scanning the ground beneath their feet, unsolved mysteries and lost cities could be explored — for the first time since they vanished.

After learning about how the ancient Roman city of Falerii Novi has been mapped using lasers, read about the ancient “City of Giants” uncovered in Ethiopia. Then, learn about McDonald’s opening a restaurant over an ancient Roman road.