Of the 166 daguerreotypes known to have been taken by James P. Ball, Glenalvin Goodridge, and Augustus Washington, 40 have just been acquired by the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Smithsonian American Art MuseumThe collection spans 286 items and dates from the 1840s to the 1920s.

Larry West was merely looking for a hobby when he visited an antique store in Mamaroneck, New York, in 1975. Fascinated by history and the visual arts, he gravitated toward an antique daguerreotype of an African American man — and spent the next 45 years curating a collection by three of the first Black photographers in America.

That trove has now been sold to the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C. It consists of 286 objects, including daguerreotypes, tintypes, and photographic jewelry, and spans from the 1840s to the 1920s.

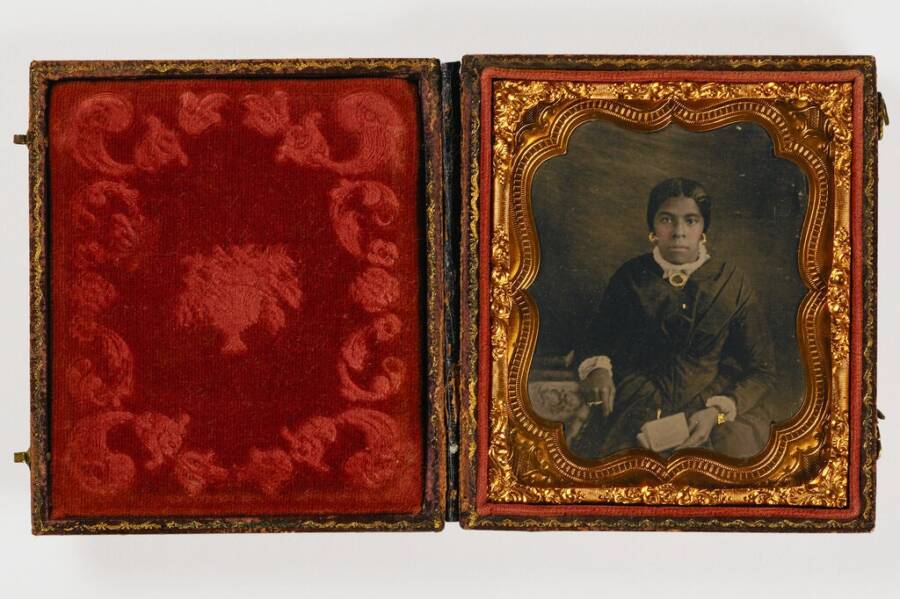

But it is the earliest daguerreotypes from the 1840s through the 1850s that have the museum most excited because they have become increasingly rare — particularly those produced by Black photographers.

Standardized in the United States in 1839, this early photography process yielded an estimated 3 to 5 million images in the country. However, only between 30,000 and 40,000 remain. For the three Black photographers whose work West collected — James P. Ball, Glenalvin Goodridge, and Augustus Washington — only 166 are known to exist.

Remarkably, West managed to collect 40 of their portraits over the last 45 years. Now officially known as the Larry J. West Collection of Photographic Jewelry, it is the most extensive collection of these three photographers’ work anywhere in America, surpassing the 26 owned by the Library of Congress.

Smithsonian American Art MuseumThe collection features a number of images with gilded embellishments or framed in pieces of jewelry.

Stephanie Stebich, director of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, called the acquisition “a transformative collection for us” that is “as rare as a hen’s teeth.”

“To know that early [African] American photographers were doing this kind of work is something we knew, but I would tell you that we have overlooked,” she said. “It’s a story that’s been marginalized. And now this will be a story that we will spotlight once again.”

Daguerreotypes were almost single-handedly responsible for giving low- and middle-income Americans the opportunity to own portraits of family or friends. Only those who could afford to sit and pay for paintings could own images of themselves before the invention, which led to a slew of studios in major cities competing for lower prices.

According to Hyperallergic, there were 71 daguerreotype studios in New York City by 1850. Subsequent technologies like ambrotypes and tintypes, which forewent the daguerreotype technique of printing on silver for glass and tin, respectively, only made visual self-representation more affordable.

“We typically view the movement from miniature painting to early cased photography as the democratization of portraiture,” said John Jacob, the Smithsonian’s McEvoy Family Curator for Photography.

The majority of exhibited daguerreotypes across the United States have represented white faces and told white stories. The rare discovery of portraits by Glenalvin Goodridge, whose father was a crucial figure in the Underground Railroad, will finally add the contributions of Black Americans to the history of photography.

Smithsonian American Art MuseumSome of the subjects featured in the collection were prominent abolitionists.

“Now, the museum is able to tell an inclusive story that places these African American photographers — Ball, Goodridge, and Washington — at the birth of American photography, conveying their importance as innovators and entrepreneurs,” said Jacob. “It’s a project that I’ve been excited about for a long time.”

Although collecting these portraits began as a hobby for West, it has become virtually an obsession in the past two decades. He has written a treatise on the images and spent hours upon hours researching the figures and photographers whose work he gathered. That material, too, will become part of the Smithsonian’s permanent collection.

But what impresses West most is the fact that these images survived at all.

“In the ’70s, you could go in antique stores and often find a box of daguerreotypes,” he said. “They were just sitting there. And I bought my first daguerreotype then, happened to be an African American, and I was fascinated.”

Initially, he began collecting these images because he respected these photographers’ success. “They succeeded in basically a white world,” he said.

Smithsonian American Art MuseumBecause daguerreotypes and ambrotypes were so delicate, they were often set in ornate cases to protect them.

When asked what West wanted visitors of the Smithsonian’s inevitable exhibition to learn, he stated that it was collaboration and unity between Black and white Americans. He explained that James P. Ball was one of the most talented and prominent African American photographers of his time for Black or white subjects.

“Ball was one of the biggest in the whole western United States,” said West.

“He opened multiple galleries. He was the man. You wanted your portrait done out there, you went to Ball. And when a tornado tore out his whole gallery, in one year and there nothing left in his book, every single thing was gone, white people came in, and they paid and bought him a whole new gallery.”

Smithsonian American Art MuseumSome of these early photographers were wearable, and were fitted with the hair of the depicted loved ones.

West himself retired as a collector in 2017 and began searching for a permanent home for his images shortly after, before landing on the Smithsonian, citing its commitment to Black artists and the museum’s resources to make these images available for research and new scholarship.

“For collector-researchers like myself, this use of the objects and research findings is critical,” he said. “It proves that anything a current collector has is not ‘owned,’ we are merely custodians for them.”

Although most of the images have never been publicly displayed, the curious will have to wait a little longer to view these historic photographs. The Smithsonian doesn’t plan to exhibit the items until after further research — and likely not until 2023.

After reading about the discovery of antique portraits by the first Black photographers, learn about seven Black inventors who shaped American history. Then, take a look at 27 stunning photos of Black women from the Victorian era.