First Movie Remake: The Great Train Robbery

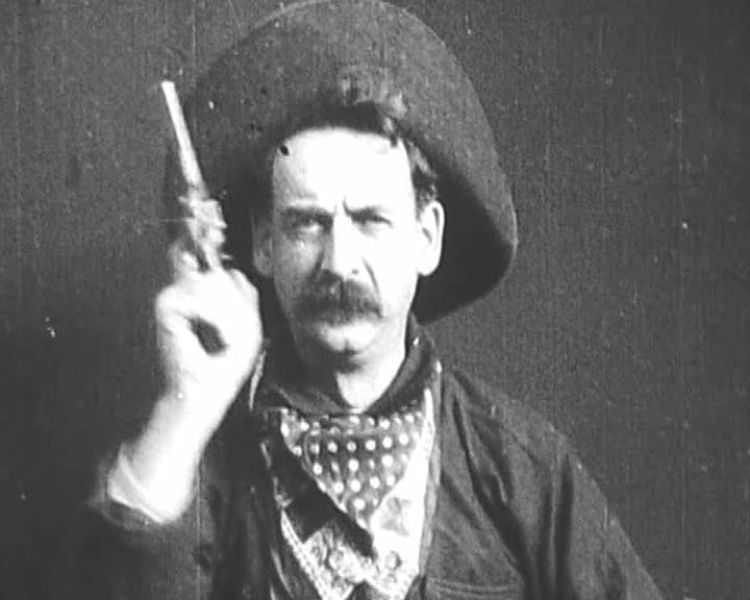

The Great Train Robbery (1903). Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

The Great Train Robbery, written, directed, and produced by Edwin S. Porter, forever changed the world of film by breaking away from the static single-shot stories of the silent era and bringing about the dynamic kind of narrative filmmaking — complete with location shooting, cross-cutting, and a moving camera — we all take for granted today.

And lest we think remakes are solely a notion of today’s Hollywood, The Great Train Robbery was indeed remade — the very next year.

The plot was simple: a group of outlaws holds up a train and is then pursued relentlessly by the sheriff and his posse. Some say it’s the first Western, some say it’s the first action film, and some just say it’s the first narrative film (as we know it today) overall.

The Great Train Robbery (1903) Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

The Great Train Robbery was also a huge success with audiences, so it didn’t take long before another filmmaker took a shot at his own version of the film (and in a fashion showing even less originality than today’s remakes). In 1904, director Siegmund Lubin released his own version of the film, under the very same name, and made it nearly identical to its predecessor. The remake featured the same plot as the original, while, much like a modern remake, pumping up the violence and the stylized production design.

That same year, a new copyright law was put into effect in order to protect physical film reels from being copied and resold for profit. But even with this new copyright law, there was no protection of intellectual property. And so, Lubin tiptoed around the copyright law and made his own version of The Great Train Robbery so that he could reap all the reward.

The Great Train Robbery (1903) Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

Profit was the motive, plain and simple. Lubin did not want to risk failure with an original film when he could easily make money by creating a nearly exact replica of an already successful film. In fact, this kind of remake, common in early Hollywood, was much more blatant and shameless than the kind of remakes we sometimes see today. It wasn’t until much later in the 20th century, and especially in recent years, that respected filmmakers found critical acclaim with successful remakes that shed new light on a great story.