Many Americans are taught that the Pilgrims and Indians gathered for a historic feast at Plymouth in 1621, but the true story of the first Thanksgiving is far more complicated.

For as long as anyone can remember, the story of the first Thanksgiving has been revered in America as a peaceful celebratory meal between the Pilgrims and the Native Americans in 1621, a year after the Pilgrims disembarked from the Mayflower.

But like most historical events that hold unsavory truths, this feast is often portrayed inaccurately. And the mythical story of the first Thanksgiving obscures the painful truths of how the relationship between the English settlers and the Indigenous people actually began.

Frederic Lewis/Archive Photos/Getty ImagesMany depictions of the Pilgrims sharing a meal with the Native Americans don’t reflect the real history of Thanksgiving.

While there was a shared feast between the two groups, it’s not known for sure why they came together or if the Native Americans were even properly invited. And they probably didn’t eat turkey — despite the popular notion that it was on the table.

More significantly, the mythical story of the first Thanksgiving whitewashes the colonial violence against the Native Americans, which occurred countless times despite this famous gathering.

Let’s take a look inside the real history of Thanksgiving.

It Wasn’t Actually The First Thanksgiving

Bettmann Archive via Getty ImagesMisleading illustrations of Thanksgiving helped to whitewash American history.

The commonly told story about the first Thanksgiving paints it as a glorious feast that established a peaceful coexistence between the Pilgrims and the Native Americans.

After the Pilgrims arrived in modern-day Massachusetts in 1620, it’s believed that they received help from members of the Wampanoag tribe. With assistance from the Native people, the Pilgrims were able to adjust to a new environment.

They were also able to have a successful fall harvest, which they marked with an elaborate celebration with the Wampanoag tribe. The festivities took place over three days, sometime between late September and mid-November in 1621. This gathering would later become known as America’s first Thanksgiving.

However, the concept of a “first Thanksgiving” itself remains questionable. Celebrating the harvest was common among both Native American and European societies — long before the so-called first Thanksgiving took place.

And Thanksgiving did not become an annual holiday right away. Historians believe that George Washington was the first to declare a national day of Thanksgiving in 1789. But this didn’t mean that all Americans knew about the “first” celebration.

Flickr CommonsThe alliance between the Pilgrims and the Wampanoag tribe was born out of necessity, not kindness.

According to the Plimoth Plantation, a living history museum in Plymouth, Massachusetts, the first Thanksgiving wasn’t even called the first Thanksgiving until the 1830s. And the holiday wasn’t made official until 1863, when President Abraham Lincoln declared it as such.

The surprising insignificance of the first Thanksgiving is reflected by how few historical accounts even mention it. Only two primary sources recount the first Thanksgiving feast — and they’re both from the settlers’ perspective.

The first account came from Edward Winslow, one of the founders of the Plymouth colony, who wrote about it in December 1621. His account was rediscovered in the mid-19th century by a Philadelphia antiquarian named Alexander Young.

He mentioned Winslow’s story in his Chronicles of the Pilgrim Fathers. In an attached footnote, Young said: “This was the first Thanksgiving, the harvest festival of New England.”

The only other account was by Plymouth Colony Governor William Bradford, who wrote about it in Of Plymouth Plantation — at least a decade after it happened. Both of these accounts were quite short — not much longer than a paragraph.

While the celebration of a bountiful harvest wasn’t exactly a new concept, the tradition of practicing gratitude on Thanksgiving caught on and has persisted to this day. However, the real history of Thanksgiving remains largely in the shadows.

Common Thanksgiving Origin Myths

Library of CongressEnglish separatists were rebranded as Pilgrims through the Thanksgiving origin myth.

It is commonly believed that after >the Pilgrims arrived in the New World, they were immediately embraced by the local Indigenous people.

But that’s not entirely true. As historian David J. Silverman points out, the myth of the first Thanksgiving has been stripped of its political realities, propagating the misperception that Native Americans just willingly gave up their land to the colonists.

“The Wampanoags had a history several thousands of years old before the English arrived,” said Silverman, who wrote the book This Land Is Their Land: The Wampanoag Indians, Plymouth Colony, and the Troubled History of Thanksgiving.

“That history shaped who they were, how they responded to other people, their connections to the land, and fundamentally shaped the history of English colonization and Indian response in southern New England.”

This history includes intertribal politics, particularly between the Wampanoag tribe and their rivals, the Narragansett tribe. And it also involves the Natives’ previous experiences with Europeans.

By the time the Pilgrims had arrived, the local Indigenous Americans had already been in contact with Europeans for about a century. And this “contact” often involved the Indigenous people being kidnapped by whites and sold into slavery.

So when the Pilgrims showed up, the Wampanoag tribe was reasonably wary of the newcomers. The feeling was mutual — especially since the Wampanoag people outnumbered the Pilgrims by “several-fold.” But despite the concerns on both sides, there were undeniable benefits of an alliance.

After all, the only way the Pilgrims were going to survive on this foreign land was to forge a relationship with the Natives who could offer them supplies and protection. Likewise, the Wampanoag tribe would benefit from the trade and military alliance with the English settlers, which could help protect them from their Narragansett rivals.

There is also the persistent myth that the Pilgrims extended a warm invitation to the Wampanoag tribe to share the feast.

But some experts believe that the Native Americans weren’t invited at all — and instead only showed up when they came to investigate after the Pilgrims fired warning shots in their direction. Others think that the Wampanoag chief Massasoit brought his men to visit the settlers on a diplomatic round — and happened upon the feast by coincidence.

As for the feast itself, many myths about that have also been spread among the American public. Most Thanksgiving paintings depict several Pilgrims with just a few Native Americans. But the real history of Thanksgiving shows that the Pilgrims were actually outnumbered about two-to-one by their Indigenous guests.

The Native Americans also brought most of the food for the meal, and the menu was quite different than the “traditional” Thanksgiving dishes we eat today.

Instead of turkey and pumpkin pie, they probably ate venison and shellfish. There were definitely no mashed potatoes, since this crop wasn’t available in the area yet. While cranberries may have been included, they were likely used as a tart garnish rather than a sweet sauce.

And since they likely had a limited supply of beer, they probably just washed the food down with water.

The Impact Of A Whitewashed Thanksgiving

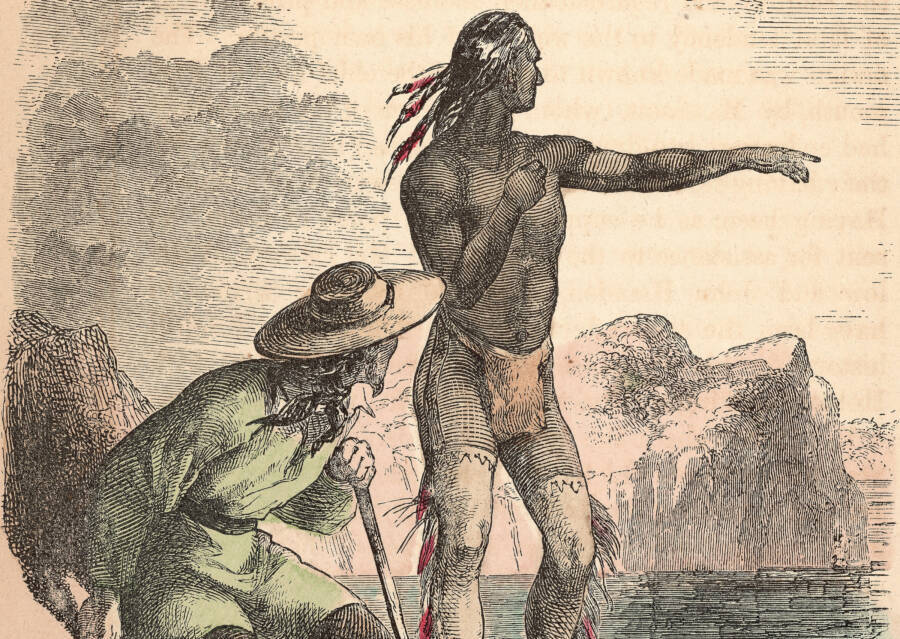

Getty ImagesA depiction of Squanto, a formerly enslaved Native American who spoke English and liaised between Indigenous people and the settlers.

Four hundred years since the so-called first Thanksgiving took place, Thanksgiving has become one of the most celebrated holidays in the U.S. But it’s hard to ignore the harmful consequences that the myth of the first Thanksgiving has had, especially on Native American communities.

The mythical story behind the holiday has led to a misrepresentation of the relationship between Native Americans and the Pilgrims — which some assume was totally harmonious.

In reality, their fraught alliance was marred by colonial land expansion, the spread of European disease, and exploitation of Indigenous resources. Before long, tensions erupted into a bloody war.

On top of that, the fairytale story depicts Indigenous Americans as being “exotic,” despite the fact that they were on the land long before the Pilgrims. Myths about Native Americans are also fueled by the long-standing tradition of young students dressing up as Pilgrims and Indigenous people — often decked out in erroneous costumes and flamboyant headgear.

“What I don’t think many people recognize, as we ask our grade school children to participate in Thanksgiving pageants and to celebrate this mythical Native American consent to colonialism — what we’re asking them to do is identify with English colonists as ‘we’ and to think of the Native historical actors as ‘them,'” Silverman said.

“In other words, it’s really a way of trying to convince Americans, especially those of European descent, to identify with the Pilgrims as fellow white people and to think of them as the proprietors of the country.”

When non-Native Americans talk about Thanksgiving, little is mentioned about what happened afterward. In the 1630s, the Pequot War erupted between the Pequot people and the English settlers, who were allied with other Native Americans.

By 1643, the colonies Plymouth, Massachusetts Bay, Connecticut, and New Haven had formed a military alliance. In the following years, this New England Confederation would fight against several Native tribes — including the Wampanoag. However, there were a couple tribes that remained allied with the English during this time, such as the Mohegan and Mohawk tribes.

And by the 1670s, a major battle erupted between the Native Americans and the settlers all over New England. This would later be known as King Philip’s War — the Native Americans’ last-ditch effort to avoid recognizing English authority and stop English settlement on their land.

However, settler violence persisted in America — and continued well after the United States gained its independence. Ironically enough, some who have heard a bit about this violent history assume that Native Americans no longer exist.

In reality, there are 574 federally-recognized tribes with thriving cultures in the United States today. And there are still Wampanoag people in Massachusetts.

Lack of awareness about the origins of Thanksgiving has severe consequences when it comes to how Americans understand their past. In short, whitewashing the true relationship between the Natives and the settlers glosses over the horrific violence against Indigenous tribes — which lasted for centuries.

Rediscovering The Real History Of Thanksgiving

Liu Guanguan/China News Service/VCG via Getty ImagesEvery year, the tribes around San Francisco gather on Alcatraz Island for the Indigenous People’s Sunrise Ceremony (or Un-Thanksgiving Day).

It wasn’t until the 1960s that some non-Native people began to rethink the way they viewed the history of Indigenous Americans. Around the same time as the Black civil rights movement, Native activists worked tirelessly to make their voices heard as well.

They wanted non-Native people to learn the largely forgotten history of colonial violence against them, which continued to impact their communities.

Since then, progress has been slow. But the myth of the Thanksgiving origin story has become increasingly challenged in recent years. Instead of celebrating the arrival of the Pilgrims, many non-Native Americans have simply chosen to emphasize spending time with their family and friends during the holiday.

Some also choose to focus on supporting Native American communities on Thanksgiving Day.

Liu Guanguan/China News Service/VCG via Getty ImagesThanksgiving is a day of mourning for many Native communities.

The movement to recognize Indigenous history has grown enough that it has compelled some support from state governments. In 2019, California Governor Gavin Newsom issued a formal apology to Native Americans for the state’s historical wrongdoings.

Meanwhile, teachers in schools across America are actively searching for ways to better educate their students on the ugly truth about the so-called first Thanksgiving.

“I believe it is my obligation as an educator,” said Virginia schoolteacher Kristine Jessup, “to ensure that history does not get hidden.”

Now that you’ve learned about the true origins of Thanksgiving, check out these weird vintage Thanksgiving ads. Next, take a look at these stunning Native American tribal masks.