For 381 straight days, virtually no people of color rode on Montgomery, Alabama buses — and it helped catalyze the entire American civil rights movement.

Rosa Parks, a catalyst of the civil rights movement in America.

Following Rosa Parks’ December 1955 arrest, upon refusing to give up her bus seat to a white man, the black community of Montgomery, Alabama — which comprised approximately 75 percent of the city’s bus-riding population — organized a movement that would hit the city right in the pocketbook.

After the 381st day, it ended segregation of the city’s buses altogether. Here’s how it happened, and why the story doesn’t actually begin with Rosa Parks.

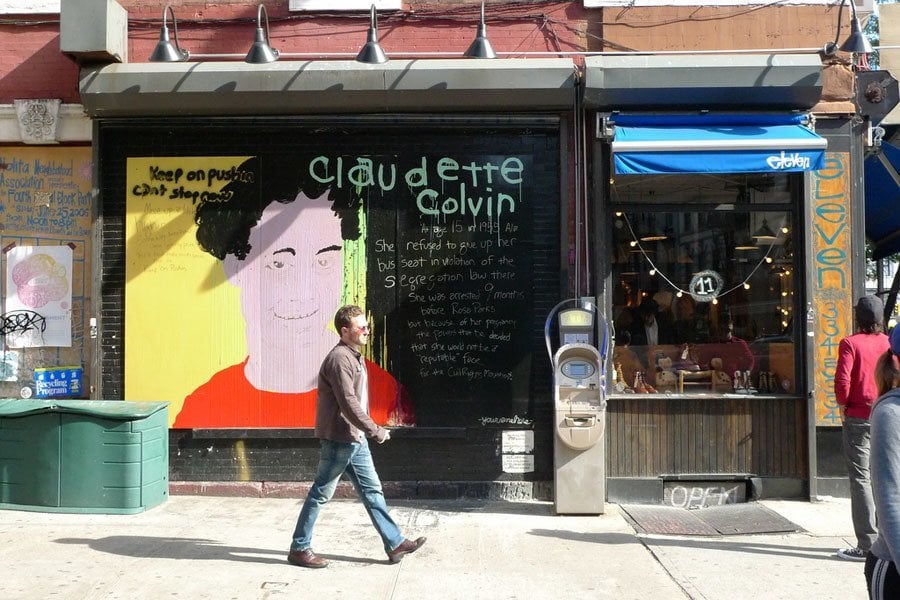

Street Art featuring Claudette Colvin. Image Source: Flickr

Found in violation of the Jim Crow laws, Claudette Colvin was just 15 years old when she was arrested for refusing to give up her seat to a white person on a bus. Even though Colvin was arrested nine months before Parks, she was not deemed a “suitable” face for the movement since she was discovered to be pregnant shortly after the incident.

Before Colvin, there was Aurelia Browder; before her, Mary Louise Smith. Before Smith, there was Irene Morgan, and before her, famous baseball player Jackie Robinson.

Indeed, all of these people defied bus segregation policies and were persecuted for their actions. It was only when the respected and educated Rosa Parks refused to move that the King-headed Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) was formed and organized a sustained bus boycott behind the more sympathetic plaintiff that was Rosa Parks. Even still, that came after the Women’s Political Council called for a Montgomery bus boycott on the night of Parks’ arrest.

The 1955 arrest of Rosa Parks. Image Source: Flickr

In comparison to what would later transpire, MIA’s original demands were humble: courteous treatment by bus operators; employment of Negro bus drivers, and first-come, first-served seating with a fixed dividing line.

The latter was especially important because at the time, whites filled in seats from the front, and black riders did the same from the back. When the bus had reached capacity, the black riders closest to the front — the “white section” — had to relinquish their seats and stand if another white person boarded the bus.

With a first-come, first-served policy, it would be harder for drivers to enact their prejudice against black riders. After all, Parks was sitting immediately behind the “white section” the day she was arrested for her failure to move from her seat. Had a solid barrier been imposed, it would have been harder — at least in a legal sense — for the driver to demand that she move.

President Barack Obama sits in Rosa Parks’ seat on the Montgomery bus. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

After the December bus boycotts began, MIA members — in tandem with attorneys Fred Gray and Clifford Durr — began looking for ways to challenge the legality of the city’s bus segregation laws. Approaching Colvin and Browder — as well as three other women who had been discriminated against via the city’s bus system — Gray filed a federal civil lawsuit on Feb. 1, 1956: Browder v. Gayle (Gayle was the surname of the then-Montgomery mayor).

The District Court reviewed the case, ultimately ruling that Alabama’s bus laws were unconstitutional, and demanded that the state of Alabama as well as the city of Montgomery end such discriminatory practices. The city and state appealed the District Court’s decision, and it wouldn’t ultimately be decided until November of that year, when the Supreme Court upheld the District Court’s ruling.

While lawyers fought in the courtroom, everyday citizens continued to exercise their power in the streets. In order to uphold the boycott, MIA organizers arranged for carpools, and black taxi drivers offered discounted rides (that is, until the city found out and fined them). But most people just chose to walk. Soon enough, support groups formed. Collecting donations from across the country, these groups would hand out shoes to replace ones that walkers had worn to shreds.

These individuals became known as “Freedom Walkers,” and while some may scoff at abstaining from a bus ride as mundane or inconsequential, when 40,000 people do that, the act becomes powerful.

Indeed, the bus system had lost nearly 80 percent of its customers during the boycott. The efforts of the Freedom Walkers — along with their combined purchasing power and the Browder v. Gayle ruling — pushed the state of Alabama to pass legislation that made it legal for African Americans to sit virtually anywhere they pleased on city buses.

Martin Luther King, Jr. is arrested in 1958, accused of loitering. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

That’s not to say that legislative shifts signaled cultural change overnight. In fact, things got considerably worse after they got legally better. Five black churches were bombed after the city passed an ordinance allowing black citizens to sit where they wished on buses, and snipers fired into buses, one shattering a pregnant African American woman’s legs. White men attacked a black teen as she was leaving the bus, and shots were fired into Martin Luther King, Jr.’s home.

In conjunction with the increased violence, newly-passed city ordinances strengthened segregation elsewhere, deeming it:

“Unlawful for white and colored persons to play together, or, in company with each other…in any game of cards, dice, dominoes, checkers, pool, billiards, softball, basketball, baseball, football, golf, track, and at swimming pools, beaches, lakes or ponds or any other game or games or athletic contests, either indoors or outdoors.”

Likewise, a grand jury sentenced King to over a year in prison for his part in the boycott, but he only served two weeks and paid a $500 fine. Parks ended up leaving Montgomery to escape death threats and avoid employment blacklisting, and historians have noted that most African Americans had returned to the habit of riding in the back of the bus by 1963, even though they weren’t required to. The Civil Rights movement still had a lot more work to do, and it expanded.

That same year, King delivered his famous “I have a Dream” speech at the March on Washington. Two years later, he helped organize the March on Selma. The movement, emblazoned by the mundane acts of a few, would go on to accomplish a string of victories.

Martin Luther King, Jr. during the March on Selma. Image Source: Flickr

As we commemorate these achievements with particular fervor this month and despair at contemporary injustices that have so far eluded similar social movements, it’s important not to lose hope. As the Freedom Walkers have shown, it’s the small steps that effects systemic change.

If you enjoyed this, be sure to check out the story of Don Diamond, a civil rights warrior in the suburbs, as well as these surprising facts about Martin Luther King, Jr.