One of the infamous "plumbers" in Richard Nixon's White House, G. Gordon Liddy was the mastermind behind the Watergate scandal.

G. Gordon Liddy entered the U.S. House of Representatives on July 20, 1972. He’d come to testify to his knowledge of the Watergate break-in that happened a month earlier. Congressman Lucien Nedzi asked Liddy: “Do you solemnly swear that the testimony you are about to give in this hearing shall be the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth?”

But Liddy did not swear to tell the truth. Instead, he simply told Nedzi that his attorney had prepared a statement. Then, Liddy’s lawyer proposed to the stunned congressman that it would be unconstitutional to force his client to take an oath and testify against his legal self-interest.

As reported by The New York Times, Nedzi noted that the argument was “highly interesting” — but irrelevant. This was Congress, not a courtroom. Liddy was a witness in a hearing, not a defendant in a trial.

But Liddy did not see himself as a witness. He saw himself as a warrior.

The Strange Early Years Of G. Gordon Liddy

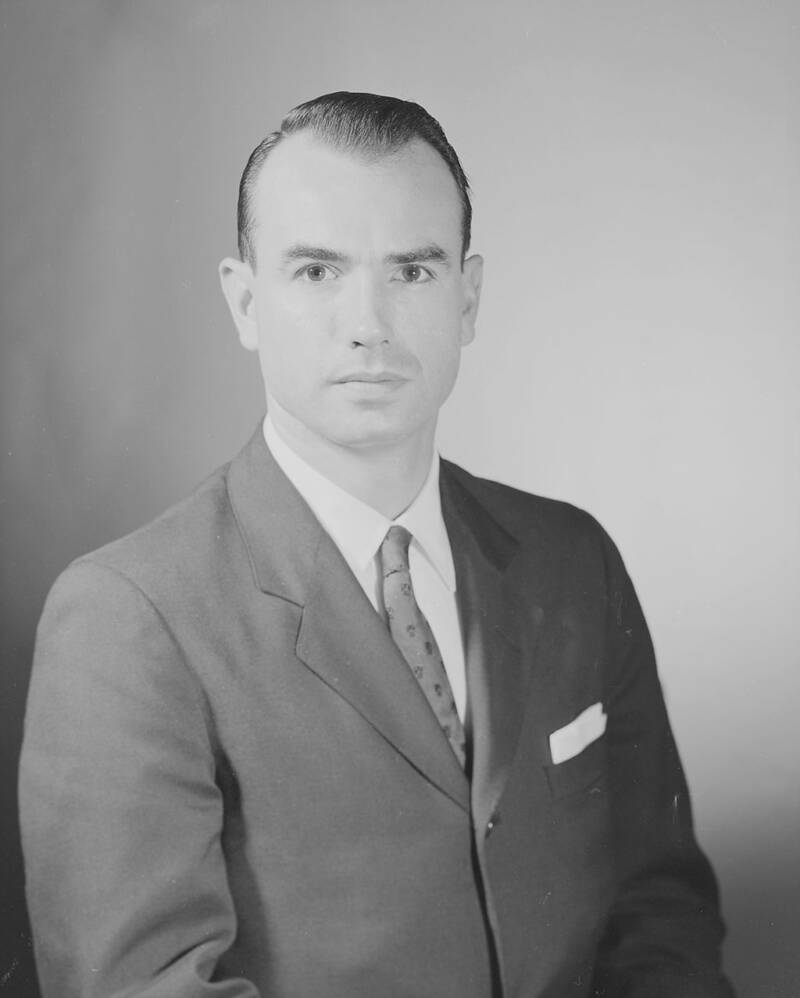

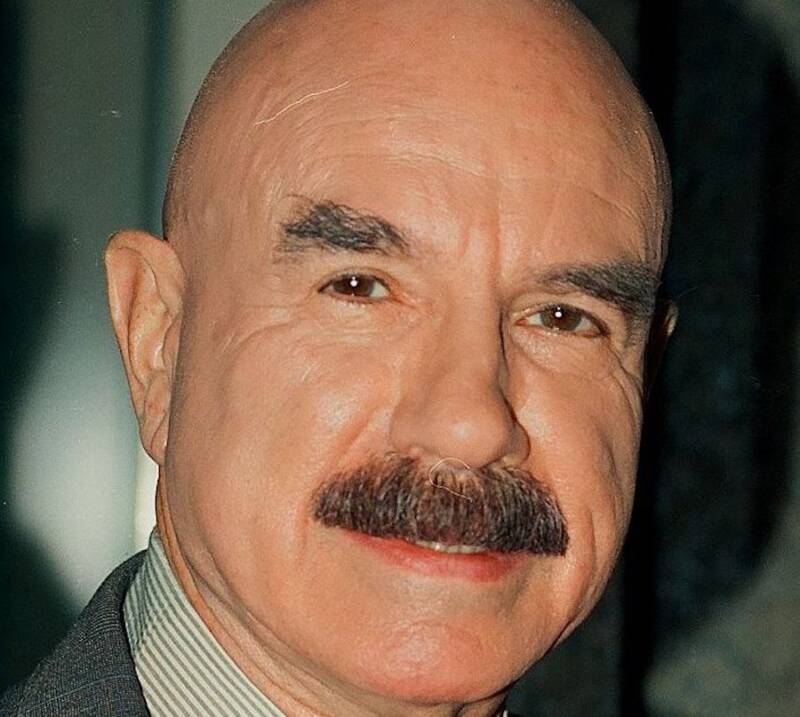

Wikimedia CommonsA professional portrait of G. Gordon Liddy, taken in 1964.

Born on November 30, 1930, George Gordon Battle Liddy enjoyed a relatively luxurious childhood. In the wealthy suburbs of New Jersey, the Liddy family maintained a maid despite the ongoing Great Depression.

Thin, frail, easily frightened, and often sick, Liddy did not leave the house much or associate with other children. Instead, he had the maid to keep him company. She happened to be a proud German immigrant.

In his 1977 memoir, Will, Liddy recalls seeing Adolf Hitler on television for the first time as a boy. He was instantly fascinated by the Nazi leader. Liddy and his maid even pantomimed “Sieg Heil” while she told stories about how Hitler had risen up to save his country in its time of need.

When Liddy later parroted this speech to his father, he was told that he didn’t know what he was talking about. But despite the admonishment, Liddy internalized what he felt was the key lesson his maid had taught him: It is the strong and powerful who get things done in this world.

G. Gordon Liddy spent the rest of his life trying to turn himself into that kind of man — and he started by overcoming his childhood fears.

In his memoir, Liddy recalls an incident when his sister’s cat left a rat out for the family. While his sister screamed and ran away, Liddy forced himself to pick up the rat barehanded. Then, he decided to take things further. Over the next hour, he skinned and roasted the rat before eating it so that rats would fear him the way they feared cats. “After all, I ate them too,” Liddy wrote.

G. Gordon Liddy’s Quest To Become A Soldier

Wikimedia CommonsG. Gordon Liddy hoped to be sent overseas to fight during the Korean War, but he was instead stationed in New York.

When World War II ended in 1945, G. Gordon Liddy mourned as the rest of the nation celebrated. As far as the 15-year-old was concerned, he had missed his once-in-a-lifetime chance to prove himself on the battlefield.

When the Korean War began in the 1950s, Liddy decided to enlist in the U.S. Army. He hoped to be sent overseas. Instead, Liddy was stationed in New York, operating the anti-aircraft batteries protecting the city.

Unable to live out his soldier fantasies abroad, Liddy began to look at options closer to home. Once he’d finished law school, Liddy joined the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). He became an agent in 1957.

Liddy discovered two new loves at the FBI. He became very attached to his sidearm, practicing so often with his pistol that he had to patch cuts on his trigger finger with super glue. And Liddy also fell in love with a woman named Frances, who he met through other Bureau members in 1957.

The couple was married within the year — although Liddy asked other agents to look into his fiancée to make sure she was “clean.”

G. Gordon Liddy’s Work With The FBI

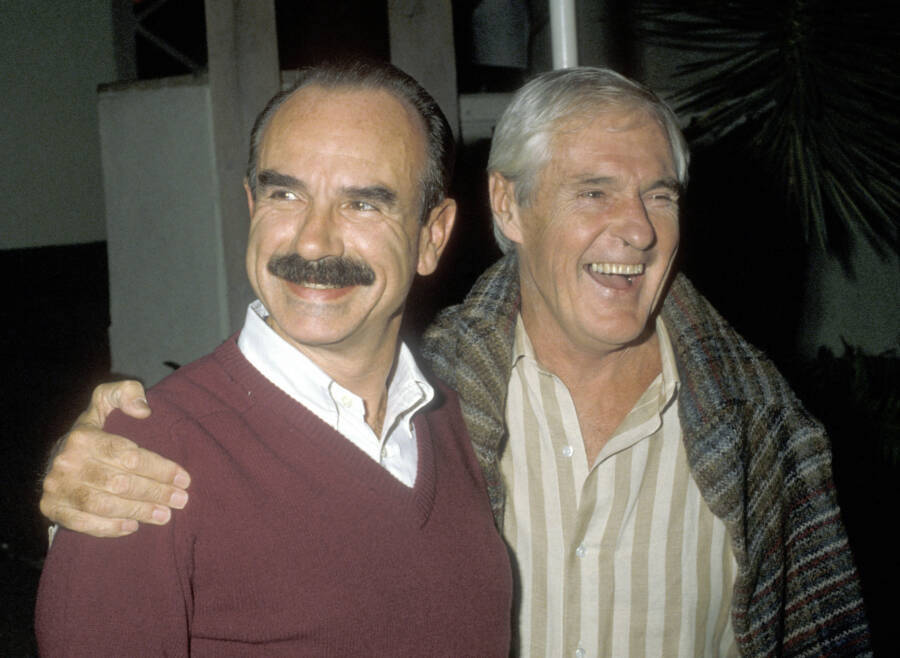

Ron Galella/Contributor/Getty ImagesThough G. Gordon Liddy (left) led a raid on LSD guru Timothy Leary’s (right) mansion in 1966, the two later formed an unexpected partnership and went on a national tour together to engage in political debates.

From the start, Liddy proved an enthusiastic member of the FBI. In 1960, the 29-year-old Liddy was made the Bureau’s youngest supervisor and moved to Washington, D.C. However, with more responsibility came more attention, and Liddy did not always have the skills to pass without incident.

In St. Louis, Missouri, Liddy was placed on a sensitive “black bag job” — essentially, kidnapping a suspect off the street — when local police arrested him. Liddy was forced to call on superior officers to bail him out.

By 1962, Liddy had resigned from the FBI despite his love of the role. Unable to support a wife and a growing family on an agent’s salary (he’d later have five children), he joined his father’s law firm in New York before finding a job as a state prosecutor in 1966. In this role, Liddy’s top focus was anti-Vietnam War protests and the civil rights movement, as well as drug crimes.

In 1966, Liddy led the raid on a Millbrook, New York mansion that was being used by Timothy Leary, a Harvard psychiatry professor turned LSD guru. This led to Leary’s first arrest and unsuccessful prosecution.

And in 1969, Liddy organized a drug raid against students at Bard College, leading to mass arrests and earning Liddy his own place in musical history. Two of the students arrested, Walter Becker and Donald Fagen, would go on to found the band Steely Dan, immortalizing Liddy as “Daddy Gee” in their song, “My Old School,” according to the Poughkeepsie Journal.

Around the same time as the infamous raid, Liddy had turned his attention to politics. His campaign for the House of Representatives ended in failure, but the appeal of power never lost its luster for him. After Richard Nixon’s election as the U.S. president in November 1968, Liddy met members of the Nixon administration. And he leaped at the chance to join Nixon’s team.

A Planner For The White House Plumbers

Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library and Museum/Wikimedia CommonsA walkie-talkie used during the Watergate break-in.

The White House Special Investigations Unit formed in 1971, with the goal to “stop security leaks and to investigate other sensitive security matters,” as reported by The New York Times. It was the job of these “plumbers” to patch leaks and “fix problems” that arose for the Nixon administration.

Nominally, G. Gordon Liddy worked for the Department of the Treasury. But his role among the plumbers was as an operational manager and idea man. While Liddy’s partner, former CIA agent E. Howard Hunt, recruited old CIA assets to help out, Liddy came up with ways to employ Hunt’s recruits. Their goal was to protect the president, and to impede Nixon’s “enemies.”

Liddy performed his part with enthusiasm — and little regard for the law.

In 1971, following the leak of the Pentagon Papers by Army Specialist Daniel Ellsberg — which revealed to the American public the deteriorating situation in Vietnam — Liddy and Hunt were tasked with fixing the leak. Liddy decided the best route was to embarrass and discredit Ellsberg.

He proposed drugging Ellsberg with military-grade LSD just before he was set to deliver a speech at a major fundraiser. The request was sent forward for approval, but by the time authorization came, the window of opportunity to strike had passed. Instead, Hunt broke into Ellsberg’s psychiatrist’s office looking for incriminating documents. He did not find any.

G. Gordon Liddy’s Dirty Tricks For “Tricky Dick”

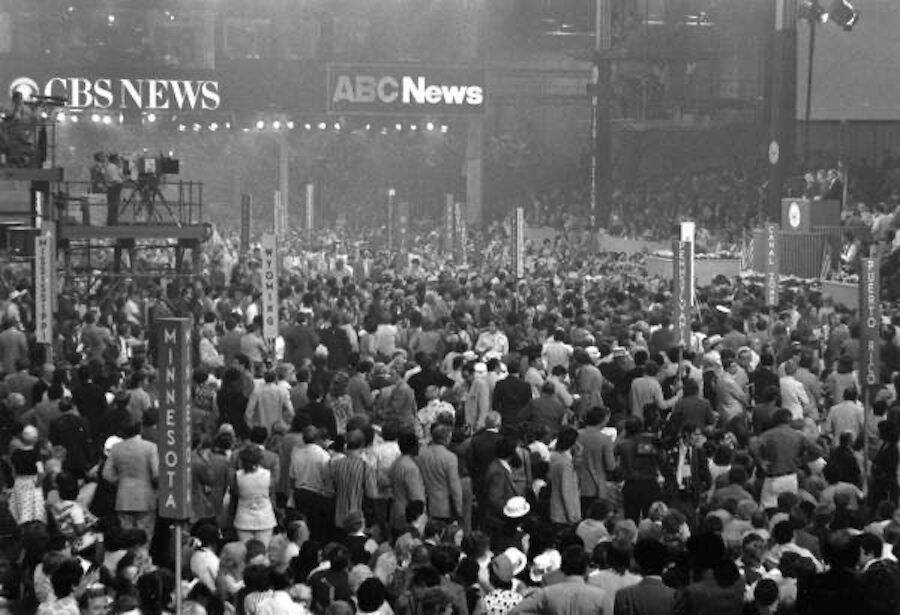

State Library and Archives of Florida/Wikimedia CommonsThe Democratic National Convention of 1972, which took place in Miami Beach, Florida.

In one of the most telling scenes from his memoir, G. Gordon Liddy recounts a meeting from around this time with E. Howard Hunt and John Mitchell — Nixon’s campaign manager and attorney general. They discussed plans for the upcoming Democratic and Republican National Conventions.

Liddy provided detailed ideas for plots against opposing politicians, civilian protestors, and even unsupportive members of the Republican Party.

Liddy’s ideas included shutting off all air conditioning at the Miami hotel slated for the 1972 Democratic National Convention, tricking prominent Democrats into compromising positions with sex workers who were disguised as socialites, breaking into Democratic planning offices to steal and copy materials, and kidnapping anti-GOP protestors and holding them in Mexico for the length of the Republican National Convention.

This last plan, designed to “strike fear into the hearts of the leftist guerillas” caught Mitchell’s attention. He asked Liddy who could possibly carry out such an operation against American civilians. Liddy responded that it would require a “Special Action Group” of trained soldiers and professional killers.

Then, to clarify, Liddy explained the origins of the idea to the attorney general, himself a World War II veteran, by using the original German. They would need an “Einsatzgruppe,” a term borrowed from the Nazi SS death squads tasked with exterminating “undesirable” people.

If the implications of this plan bothered Mitchell, Liddy does not mention it in his memoir. In fact, Mitchell only objected to another plan — this one targeting Nixon’s upcoming election opponent Senator George McGovern.

Liddy explained to Mitchell that he could pay a group of hippies to come in and urinate on McGovern’s hotel room rug during a press conference. Mitchell laughed but told Liddy to forget it. The attorney general realized that was the same room he was scheduled to stay in the next day.

Mayhem, Sure. But Murder?

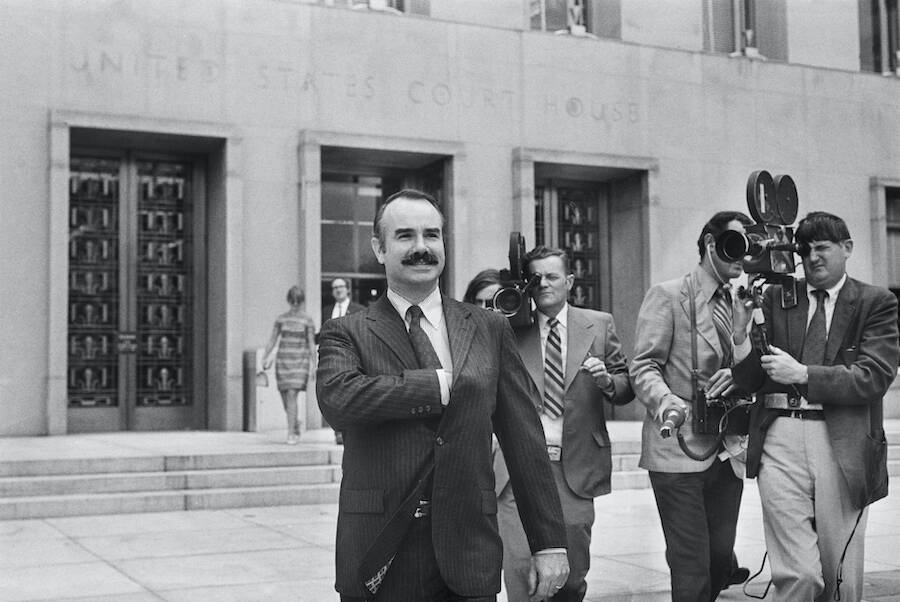

Bettmann/Contributor/Getty ImagesG. Gordon Liddy leaving the U.S. District Court, where he pleaded not guilty to breaking into the Democratic National Headquarters at Watergate in 1972.

In February 1972 — according to G. Gordon Liddy’s memoir — E. Howard Hunt approached Liddy with important news from the White House. Veteran reporter Jack Anderson had been a major thorn for the administration for three years, but his most recent article had finally gone too far. Infuriated that Anderson may have endangered the safety of an undercover asset, Hunt said that they were tasked with taking the writer out.

By his own admission, Liddy suggested that Anderson could fall victim to violent street crime. Innocent people could get caught in the crossfire between gangs at any time, Liddy suggested, and if the Cuban operatives Hunt had access to were up for the job… He did not finish the implication.

Hunt asked whether involving the Cubans in the plot was too risky. If they were caught, it could cause some major problems. Liddy responded that in that case, he would simply kill Anderson himself.

In an interview with Anderson in 1991, Liddy even told Anderson of the plot, as reported by the Associated Press. “The rationale was to come up with a method of silencing you through killing you,” he told Anderson.

But the White House ultimately nixed the plan.

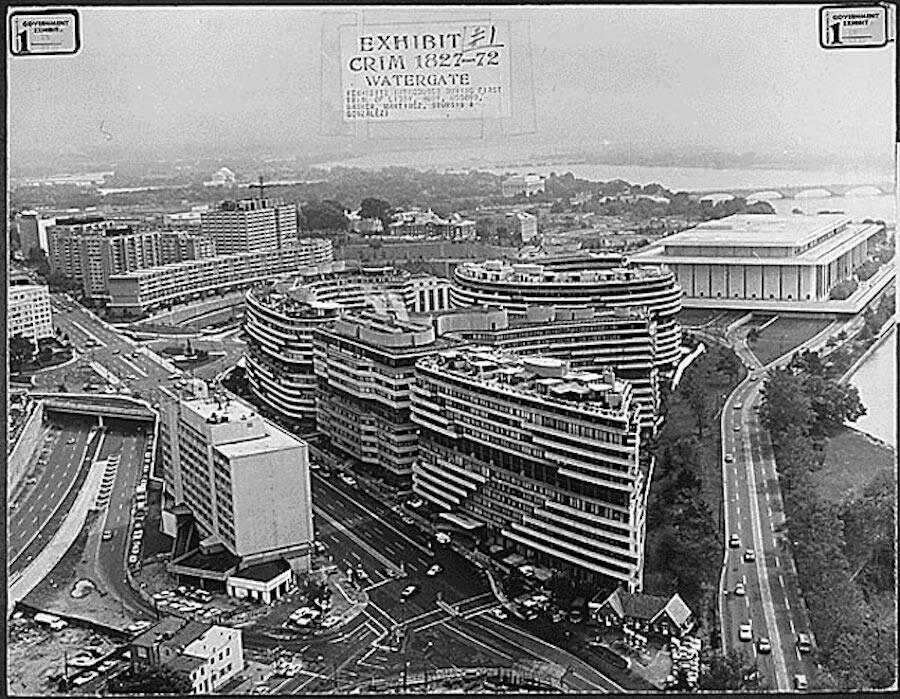

The Botched Break-In At The Watergate Complex

Gerald R. Ford Library & Museum/Wikimedia CommonsThe Watergate complex, pictured circa 1972. This photo was the first exhibit used in the Senate investigation during the Watergate scandal.

Most of G. Gordon Liddy’s bizarre and illegal plots were never carried out. But the Watergate break-in was a notable exception.

In May 1972, Hunt’s Cuban operatives broke into the Democratic National Committee’s offices at the Watergate complex in Washington, D.C. That time around, they managed to enter and exit undetected.

The operatives planted bugs and copied confidential campaign information for the president. But it was later discovered that the listening devices were malfunctioning and would have to be replaced with new ones.

In the early hours of June 17, 1972, Hunt, Liddy, and their team of five burglars assembled outside the complex. Hunt and Liddy then watched the break-in unfold from a Watergate Hotel room, and Hunt became spooked.

They’d planned to tape open a maintenance door, but someone onsite had apparently found the tape and removed it. They could retape the door, wait, and then proceed as planned, or, they could try again another day.

Liddy was left to make the call — and he told them to move forward with their plan. While Hunt and Liddy watched their team progress up the building through binoculars, a guard noticed the newly taped door that he had already fixed earlier that night. He called the police.

After Hunt and Liddy watched the others get arrested, they quickly fled. Liddy returned home and climbed into bed next to his wife. She asked him how things had gone. And he replied, “I’ll probably be going to jail.”

The Last Defender

Wikimedia CommonsG. Gordon Liddy, pictured in 1998.

Hunt and the other burglars all agreed to work with the prosecution. G. Gordon Liddy was the lone hold-out. Although the Nixon administration offered him a $30,000-per-year pension, a pardon within three years, and sentencing to a low-security prison near his home in exchange for his silence, Liddy needed no incentive. For him, it was a matter of honor.

According to Liddy’s memoir, when Hunt confessed that he was talking to prosecutors, Liddy immediately assumed he would have to kill him. He claims that he set a plan into motion, using connections he had made in prison to poison Hunt’s food while he himself was in solitary confinement, and awaited orders from the White House. The order never came.

Hunt lived. And Liddy never spoke to him again.

With the Watergate scandal spelling the end of Nixon’s presidency, Liddy did not get the pardon that he’d hoped for — and he was ultimately sentenced to 20 years in prison. Even with Gerald Ford in power, Liddy remained behind bars. But in the end, he served a little over four years after Jimmy Carter reduced his sentence in 1977. Liddy was released later that same year.

In one incident that speaks volumes about his time in incarceration, Liddy allowed one inmate to burn a quarter-sized hole in his palm with a cigarette lighter to prove his toughness. After that, other prisoners left Liddy alone.

After he was released from prison, Liddy published his tell-all memoir to help pay off his legal fees. He later found success as a conservative commentator, author, and radio personality until his death at age 90 in 2021.

Liddy may have been one of the scariest henchmen in Nixon’s administration, but part of Liddy’s lasting appeal to audiences was his infamous sense of humor. In the mid-1980s, he and Timothy Leary — the same man he organized a drug raid against in 1966 — appeared on a college lecture tour together called Nice Scary Guy vs. Scary Nice Guy.

Who was who? It was sometimes difficult to tell.

After reading about G. Gordon Liddy, learn about Martha Mitchell, the woman who tried to blow the whistle on the Watergate scandal. Then, take a look at the history of presidential impeachments in the United States.