Born with a rare form of albinism in the Jim Crow South, George and Willie Muse were spotted by a showman and forced into a life of exploitation.

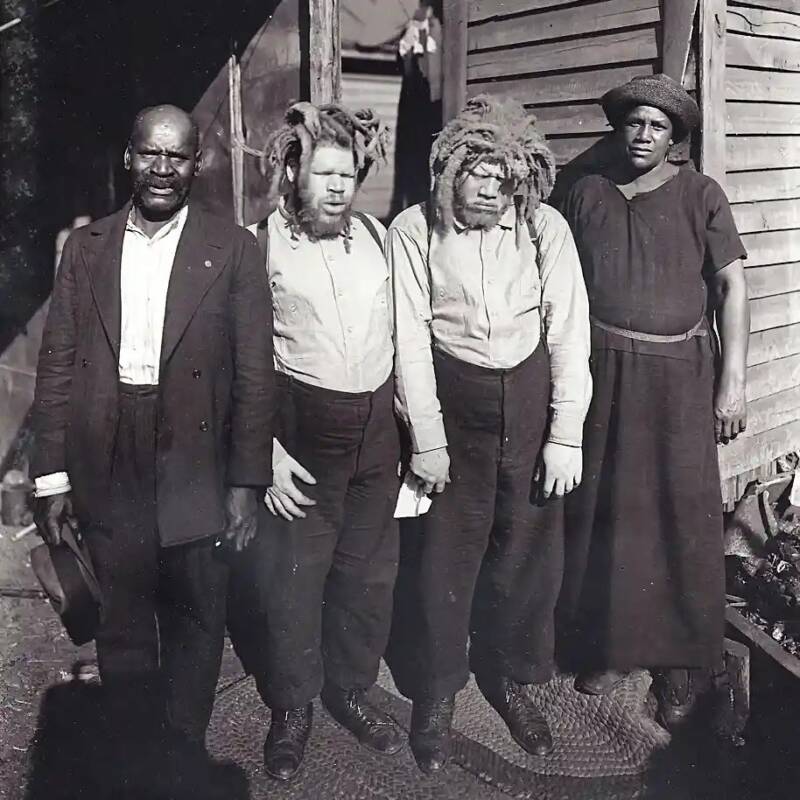

PRGeorge and Willie Muse, who were both born with albinism, stand with their parents after their harrowing experience in the circus as “Eko and Iko.”

In America’s era of sideshow “freaks” in the early 20th century, many people were bought, sold, and exploited like prizes for indifferent circus promoters. And perhaps no performer’s tale is as harrowing as that of George and Willie Muse.

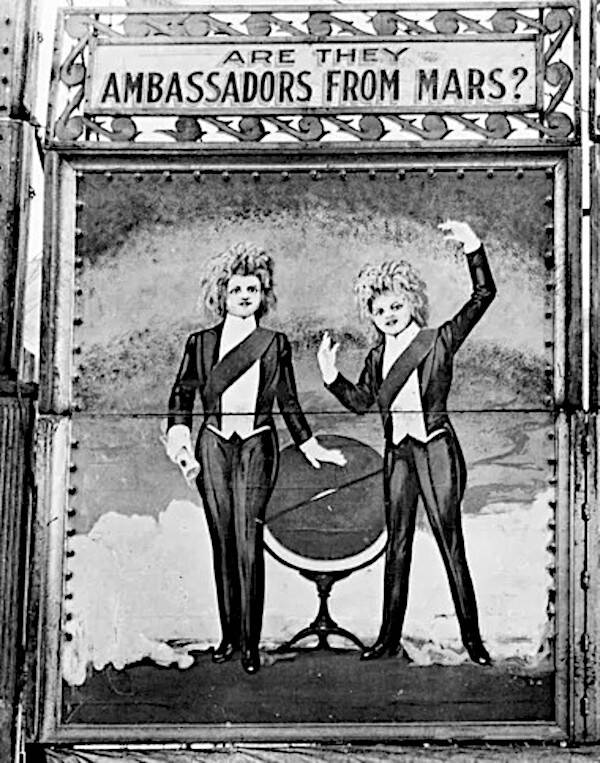

In the early 1900s, the two Black brothers were reportedly abducted from their family’s tobacco farm in Virginia. Desired for show business because they were both born with albinism, the Muse brothers traveled against their will with a promoter named James Shelton, who billed them as “Eko and Iko, the Ambassadors from Mars.”

All the while, however, their mother battled racist institutions and indifference to free them. Through deception, cruelty, and many court battles, the Muse family succeeded in reuniting with one another. This is their story.

How George And Willie Muse Were Abducted By The Circus

Macmillan PublishersGeorge and Willie were displayed under an array of humiliating names, complete with absurd backgrounds tailored to racist beliefs of the time.

George and Willie Muse were the eldest of five children born to Harriett Muse in the small community of Truevine on the edge of Roanoke, Virginia. Against almost impossible odds, both boys were born with albinism, leaving their skin exceptionally vulnerable to the harsh Virginia sun.

Both also had a condition known as nystagmus, which often accompanies albinism, and weakens vision. The boys had begun squinting in the light from such a young age that by the time they were six and nine years old, they had permanent furrows in their foreheads.

Like most of their neighbors, the Muses eked out a bare living from sharecropping tobacco. The boys were expected to help out by patrolling the rows of tobacco plants for pests, killing them before they could damage the precious crop.

Although Harriett Muse doted on her boys as best she could, it was a hard life of manual labor and racial violence. At the time, lynch mobs frequently targeted Black men, and the neighborhood was always on the edge of another attack. As Black children with albinism, the Muse brothers were at a heightened risk of scorn and abuse.

It’s not known for certain how George and Willie came to the attention of circus promoter James Herman “Candy” Shelton. It’s possible that a desperate relative or neighbor sold him the information, or that Harriett Muse allowed them to go with him temporarily, only for them to be kept in captivity.

According to Truevine author Beth Macy, the Muse brothers might have agreed to do a couple performances with Shelton when his circus came through Truevine in 1914, but then the promoter abducted them when his show left town.

The popular story which sprang up in Truevine was that the brothers were out in the fields one day in 1899 when Shelton lured them with candy and kidnapped them. When night fell and her sons were nowhere to be found, Harriett Muse knew something terrible had happened.

Forced To Perform As ‘Eko And Iko’

Library of CongressBefore television and radio, circuses and traveling carnivals were a leading form of entertainment for people throughout the United States.

In the early 20th century, the circus was a major form of entertainment for most of America. Sideshows, “freak shows,” or demonstrations of unusual skills like sword swallowing, cropped up all over the country.

Candy Shelton realized that in an era when disabilities were treated as curiosities and Black people had little to no rights that a white man would respect, the young Muse brothers could be a goldmine.

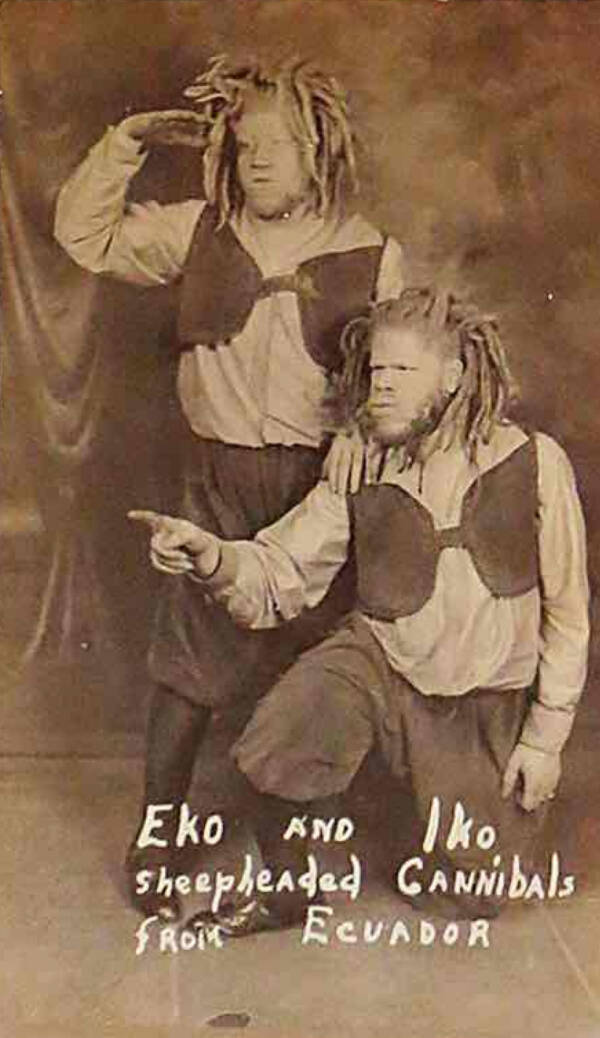

Until 1917, the Muse brothers were displayed by managers Charles Eastman and Robert Stokes in carnivals and dime museums. They were advertised under such names as “Eastman’s Monkey Men,” the “Ethiopian Monkey Men,” and the “Ministers from Dahomey.” To complete the illusion, they were often forced to bite the heads off of snakes or eat raw meat in front of paying crowds.

After a murky series of exchanges in which the brothers were palmed off between a string of managers, they came once more under the control of Candy Shelton. He marketed the brothers as the “missing link” between humans and apes, claimed they came from Ethiopia, Madagascar, and Mars, and descended from a tribe in the Pacific.

Willie Muse later described Shelton as a “dirty rotten scumbag,” who expressed immense indifference toward the brothers on a personal level.

Shelton knew so little about them, in fact, that when he handed the Muse brothers a banjo, a saxophone, and a ukulele as photo props, he was shocked to discover that they could not only play the instruments but that Willie could replicate any song after hearing it just once.

The Muse brothers’ musical talent made them all the more popular, and in cities across the country, their fame grew. Then Shelton eventually struck a deal with circus owner Al G. Barnes to attach the brothers as a sideshow. The agreement rendered George and Willie Muse “modern-day slaves, hidden in plain sight.”

As Barnes bluntly put it, “We made the boys a paying proposition.”

Indeed, although the boys could bring in as much as $32,000 a day, they were likely only paid just enough to survive on.

Macmillan PublishingWillie, left, and George, right, with circus owner Al G. Barnes, for whom they performed as “Eko and Iko.”

Behind the curtain, the boys cried out for their family, only to be told: “Be quiet. Your momma is dead. There’s no use even asking about her.”

Harriett Muse, for her part, exhausted every resource trying to find her sons. But in the racist atmosphere of the Jim Crow South, no law enforcement official took her seriously. Even the Humane Society of Virginia ignored her pleas for help.

With another son and two daughters to care for, she married Cabell Muse around 1917 and moved into Roanoke for better pay as a maid. For years, neither she nor her absent sons lost faith in their belief that they would be reunited.

Then, in the fall of 1927, Harriett Muse learned that the circus was in town. She claimed that she saw it in a dream: her sons were in Roanoke.

The Muse Brothers Return To Truevine

Photo courtesy of Nancy SaundersHarriett Muse was known in her family as an iron-willed woman who protected her sons and battled for their return.

In 1922, Shelton took the Muse brothers to the Ringling Bros. Circus, drawn by a better offer. Shelton shaped their blond hair into outlandish locks that shot out of the tops of their heads, dressed them in colorful, strange garments, and claimed they’d been found in the wreckage of a spaceship in the Mojave Desert.

On Oct. 14, 1927, George and Willie Muse, now in their mid-30s, pulled back into their childhood home for the first time in 13 years. As they launched into “It’s a Long Way to Tipperary,” a song which had become a favorite of theirs during World War I, George spotted a familiar face at the back of the crowd.

He turned to his brother and said, “There’s our dear old mother. Look, Willie, she is not dead.”

After over a decade of separation, the brothers dropped their instruments and embraced their mother at last.

Shelton soon appeared demanding to know who it was who’d interrupted his show, and told Muse that the brothers were his property. Undaunted, she firmly told the manager that she wasn’t leaving without her sons.

To the police who arrived soon after, Harriett Muse explained that she’d allowed her sons to be taken for a few months, after which they were to be returned to her. Instead, they’d been kept indefinitely, allegedly by Shelton.

The police seemed to buy her story and agreed that the brothers were free to go.

Justice For The ‘Ambassadors From Mars’

PR“Freak show” managers often supplemented their profits by peddling postcards and other memorabilia of “Eko and Iko.”

Candy Shelton didn’t give up the Muse brothers so easily, but neither did Harriett Muse. Ringling sued the Muses, claiming that they’d deprived the circus of two valuable earners with legally binding contracts.

But Harriett Muse shot back with the help of a local lawyer and won a series of lawsuits confirming her sons’ right to payment and visits home in the off season. That a middle-aged, Black maid in the segregated South managed to win against a white-owned company is testament to her resolve.

In 1928, George and Willie Muse signed a new contract with Shelton which contained guarantees of their hard-won rights. With a fresh name change to “Eko and Iko, Sheep-Headed Cannibals from Ecuador,” they embarked on a world tour beginning at Madison Square Garden and going as far afield as Buckingham Palace.

Although Shelton still behaved as though he owned them and regularly stole from their wages, George and Willie Muse did manage to send money home to their mother. With these wages, Harriett Muse bought a small farm and worked her way out of poverty.

When she died in 1942, the sale of her farm enabled the brothers to move into a house in Roanoke, where they spent their remaining years.

Candy Shelton finally lost control of “Eko and Iko” in 1936 and was forced to make a living as a chicken farmer. The Muses went to work under slightly better conditions until they retired in the mid-1950s.

In the comfort of their home, the brothers were known to tell rambling stories of their harrowing misadventure. George Muse died of heart failure in 1972 while Willie carried on until 2001 when he died at the age of 108.

After learning about the Muse brothers’ tragic story as “Eko and Iko,” read the sad, true stories of the Ringling Brothers’ best-known “freak show” members. Then, take a look at some of the most popular sideshow “freaks” from the 20th century.