In China from the 10th century until 1905, those convicted of crimes like high treason and mass murder could be sentenced to death by lingchi, a gruesome execution method in which victims were cut apart piece by piece until they died.

Warning: This article contains graphic descriptions and/or images of violent, disturbing, or otherwise potentially distressing events.

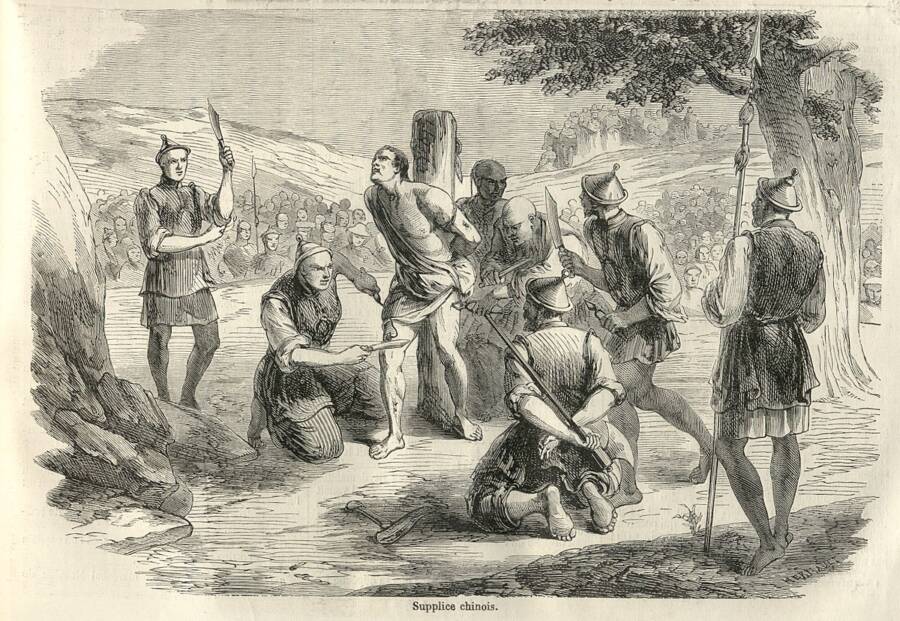

Public DomainAn 1858 illustration from a French newspaper showing the lingchi execution of Auguste Chapdelaine, a missionary to China.

For 1,000 years, beginning around the 10th century C.E., one form of capital punishment in China set itself apart for its particularly cruel and brutal technique: lingchi.

Lingchi loosely translates to “slow slicing” or “death by a thousand cuts.” As the name implies, it was a drawn-out and brutal process wherein an executioner would deliver justice to perpetrators of particularly heinous crimes by administering a series of cuts to their skin.

Unlike most execution methods, which aim to kill sooner rather than later, the intention of lingchi was to inflict a long, slow punishment to make the criminal suffer as much as possible.

The practice was officially outlawed by the Qing dynasty government in 1905, but its gruesome legacy lingers to this day.

What Was Lingchi And How Was It Performed?

The procedure for performing lingchi was fairly straightforward. It called for executioners to tie the condemned person to a wooden post so they were unable to move or break free from their binds.

Wellcome CollectionA 19th-century rice paper painting of a woman being slowly sliced to pieces.

Some accounts, like that of George Ernest Morrison, the author of the 1895 book An Australian in China, noted that the prisoner was dosed with opium prior to the execution.

“The prisoner is tied to a rude cross: he is invariably deeply under the influence of opium. The executioner, standing before him, with a sharp sword makes two quick incisions above the eyebrows, and draws down the portion of skin over each eye, then he makes two more quick incisions across the breast, and in the next moment he pierces the heart, and death is instantaneous. Then he cuts the body in pieces; and the degradation consists in the fragmentary shape in which the prisoner has to appear in heaven.”

As detailed above, the executioner would administer cuts to bare flesh, usually starting at the chest, where the breast and surrounding muscles were methodically removed until the ribs were almost visible. Next, the executioner would make his way over to the arms, cutting away large portions of skin and exposing muscle tissue in an excruciating bloodbath before moving down to the thighs, where he would repeat the process.

By this point, the victim would have likely died. Executioners would then collect the severed limbs and place them in a basket.

As Chinese law didn’t specify any particular method of delivery, the act of lingchi tended to vary by region. Some accounts report that the punished were dead in less than 15 minutes, while other cases apparently went on for hours, forcing the accused to withstand up to 3,000 cuts.

PHGCOM/Wikimedia CommonsLingchi was also practiced in Vietnam, where executioners took the life of French missionary Joseph Marchand using the gruesome method in 1835.

These details would depend on the depth of each incision as well as the skill level of the executioner and the severity of the crime.

Officials would reportedly sometimes take pity on those charged with lesser offenses, limiting their time spent suffering. Families who could afford to would often pay to have their condemned relatives killed right away, ensuring that the first cut would be the last one — and sparing them from hours of excruciating torture.

Who Fell Victim To The Brutal Execution Method?

Not everyone was subject to die in such a cruel and unusual way, as lingchi was reserved for only the worst crimes, such as treason, mass murder, patricide, and matricide. One man was condemned to execution by lingchi for raping 182 women. And in 1542, 16 palace maids were reportedly sentenced to the brutal death for attempting to assassinate the emperor.

Another 16th-century report of lingchi tells of the death of Liu Jin, a eunuch who served the Zhengde Emperor. In 1510, he was sentenced to death for seizing too much power from the ruler. Legend says that he suffered more than 3,000 cuts over a two-day period before he died, and the people of Beijing reportedly paid for pieces of his flesh and ate them with rice wine.

In his 1895 book The Peoples and Politics of the Far East, English journalist and Parliament member Sir Henry Norman published a snippet from a Chinese newspaper that described one woman’s lingchi sentence:

“Ma Pei-yao, Governor of Kuangsi, reports a triple poisoning case in his province. A woman having been beaten by her husband on account of her slovenly habits, took counsel with an old herb woman, and by her direction picked some poisonous herb on the mountain, with which she successively poisoned her husband, father-in-law, and brother-in-law. She has been executed by the slow process.”

While many ancient accounts of lingchi were likely mythologized, fitting a sensationalized Western narrative that depicted the “savage” practices of the then-mysterious Chinese populace, one case provided photographic evidence of such cruelty.

National Library of FranceFu Zhuli was the last person officially put to death by lingchi by the Chinese government before it was banned in 1905.

French travelers caught the execution of Fu Zhuli by lingchi on camera. He was convicted in 1905 of murdering his master, a Mongolian prince, and was the last known execution by lingchi before the Chinese government banned death by a thousand cuts just weeks later.

The Abolishment Of Lingchi As A Method Of Punishment

The practice of lingchi was controversial from the very beginning. As early as the 12th century, Chinese citizens were speaking out against it. The poet and historian Lu You wrote a letter to the imperial court of the Song dynasty arguing, “When the muscles of the flesh are already taken away, the breath of life is not yet cut off, liver and heart are still connected, seeing and hearing still exist. It affects the harmony of nature, it is injurious to a benevolent government, and does not befit a generation of wise men.”

The horror of lingchi came not only from the painful act itself but also from its meaning for those subjected to it. According to the Confucian ideal of filial piety, or loyalty to one’s family, altering a victim’s body meant that they would not be “whole” in the afterlife.

Thus, the act was both a type of public humiliation and a death sentence, both literally and spiritually. That explains why it was only reserved for the most heinous or rebellious offenses.

Wellcome CollectionA model depicting the “death by a thousand cuts” execution method.

Despite the controversy surrounding lingchi, however, it continued as a practice for at least 1,000 years. Although the punishment was officially outlawed in 1905, there are several alleged accounts of its occurrence throughout the early 20th century.

When Yang Zengxin, the governor of Sinkiang, was assassinated in 1928, the man believed to be responsible for his death was reportedly executed by lingchi — but he was forced to watch his daughter die first. And in 1936, a Communist rebellion leader was allegedly put to death using the cruel method. However, there were purportedly no official sentences of lingchi after 1905.

Regardless of exactly when the last lingchi execution occurred, the grisly practice fell out of favor a century ago — but it was an act so shocking that it won’t soon be forgotten.

After learning about the history of lingchi, or “death by a thousand cuts,” read about the practice of defenestration. Then, go inside the 10 worst execution methods ever devised.