In March 1898, two lions began killing and feasting upon construction workers who were building a railway bridge in Kenya's Tsavo region, resulting in up to 135 deaths before these fearsome beasts were finally killed nine months later.

Jeffrey Jung/Wikimedia CommonsThe man-eating Tsavo lions on display at Chicago’s Field Museum. The male lions are maneless due to the extreme heat and thorny vegetation in the Tsavo region of Kenya.

In 1898, an estimated 135 Indian and African workers who were building a railway bridge over the Tsavo River in Kenya were attacked in their tents at night and killed by two man-eating lions. Over nine terrifying months, it fell on Lieutenant Colonel John Henry Patterson, the British officer overseeing the bridge’s construction, to track down, outwit, and kill the Tsavo lions — a formidable task that almost ended in Patterson’s death.

To the workers, the man-eaters were not lions but “demons,” ones they dubbed “The Ghost” and “The Darkness.” To Patterson, they were simply beasts with a rational reason for their unnatural taste for human flesh.

Whatever the cause, Patterson had his work cut out for him. Shortly after his arrival in March 1898, workers started disappearing in the night.

It wasn’t until December that Patterson was able to shoot both Tsavo lions, bringing an end to their reign of terror. Today, the creatures are on display in the Field Museum in Chicago, where visitors can see the final, terrifying sight that the lions’ victims opened their eyes to before they were viciously mauled.

The Tsavo Man-Eaters Begin Terrorizing Railway Workers

Soon after Patterson arrived in Kenya to oversee the railway bridge project in 1898, he was informed of attacks that were taking place in the camps where workers, who were mostly Indian and African, slept at night.

Nina R/Wikimedia CommonsKenya’s Tsavo region, where The Ghost and The Darkness killed dozens of railroad workers in 1898.

Upon investigation, Patterson found a lion’s “pugmarks,” or footprints, and a trail of marks left by a victim’s heels as he was dragged from his tent across the terrain. Following the trail, he was soon confronted with a gruesome spectacle, as he wrote in his 1907 book The Man-Eaters of Tsavo and Other East African Adventures.

“The ground all round was covered with blood and morsels of flesh and bones, but the unfortunate jemadar’s head had been left intact, save for the holes made by the lion’s tusks on seizing him… the eyes staring wide open with a startled horrified look in them,” Patterson wrote.

Patterson, with a rifle in hand, spent the night perched in a tree overlooking the deceased man’s tent. Out of the darkness, he heard a lion’s roar in the distance and the panicked cries of people at another camp. But he could do nothing — a pattern that would become all too common.

Public DomainLieutenant Colonel John Henry Patterson, the man who killed the Tsavo lions.

The tents that housed two or three thousand men were scattered over eight miles, too wide of an area for Patterson to patrol. Over the next few months, efforts were made to keep the Tsavo lions out of the camps. Bomas, or thorny walls made from acacia tree branches, were erected around campsites, while bonfires blazed all night within the enclosures to scare the lions called The Ghost and The Darkness away.

But the Tsavo lions were persistent. They jumped over or dug under the thorn walls and were unafraid of fire. Brazenly, they snatched men out of their tents and often feasted on them in front of their horrified peers.

Soon, hundreds of terrified men had left, following the construction of the railhead as it pushed farther beyond the Tsavo region. The remaining men were concentrated in larger camps around the bridge. With less territory to patrol, Patterson was more likely to encounter the lions.

And encounter them he did.

How Patterson Hunted Down The Ghost And The Darkness

After a series of traps that Patterson built to capture the Tsavo lions failed, he knew he had to try something else. Construction of the bridge had ground to a halt as most of the workers fled, unwilling to become a meal for The Ghost and The Darkness.

Then, on Dec. 9, 1898, nine months after the attacks began, Patterson finally got his chance to kill one of the man-eaters.

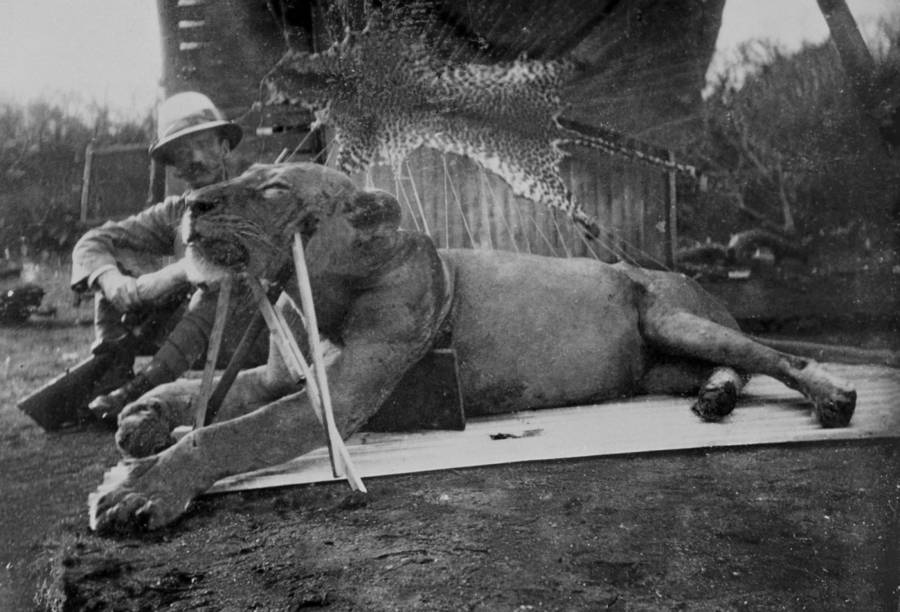

Public DomainLt. Col. Patterson posing with the first dead lion.

Using a donkey carcass as bait, he climbed into a platform he had built in a tree and waited for the lions to investigate. Soon, however, “the hunter became the hunted,” as Patterson wrote in his book. “[I]nstead of either making off or coming for the bait prepared for him, the lion began stealthily to stalk me! For about two hours he horrified me by slowly creeping round and round my crazy structure, gradually edging his way nearer and nearer.”

Then, as the lion crept toward Patterson to go in for the kill, Patterson began firing his gun. The first Tsavo Man-Eater was dead.

The second lion did not go so easily.

Although Patterson managed to shoot the creature not long after killing the first lion, he wasn’t confident that the injuries he’d inflicted were fatal. It disappeared for 10 days, and the men at the camp began to be hopeful that their ordeal was over. Then, the remaining Tsavo Man-Eater made a surprise attack on a worker on Dec. 27. The following night, Patterson shot it twice, but he only injured it again. The lion bolted, leaving a trail of blood for Patterson and his men to follow.

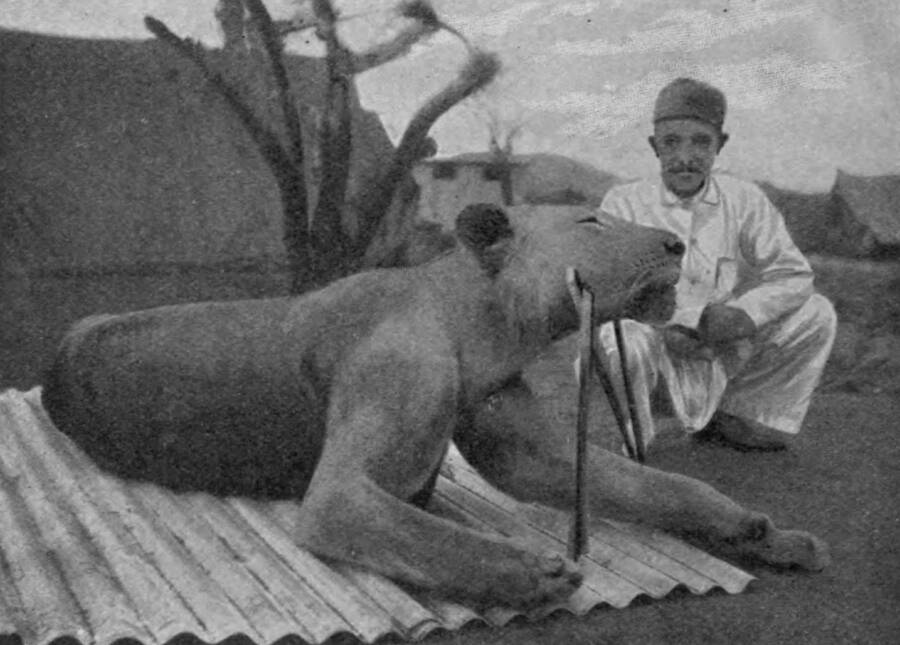

Public DomainIt took Lt. Col. Patterson several weeks and multiple shots to take the final lion down.

They found the beast hiding in a thicket. Now threatened, it charged the men. As it did, Patterson fired four shots into it, but with little effect.

Out of bullets, Patterson was forced to climb a tree, just narrowly escaping attack. From his position, Patterson grabbed a rifle from one of his men and shot the lion again, knocking it to the ground.

The lion was motionless, so Patterson jumped down — but as soon as he did, it was on its feet and barreling towards him. Patterson stood his ground, took aim, and fired two shots, one into its chest and the other into its head. Finally, the lion collapsed dead just feet away from him.

After nine months of terror, the lions known as The Ghost and The Darkness were dead. Patterson reportedly had their skins made into rugs that he used on his floor for the next 25 years. In 1924, they were sold to the Field Museum in Chicago, where the lions were stuffed and put on display. They remain there to this day.

What Caused The Tsavo Lions To Become Man-Eaters?

Lions near the Tsavo River today do not exhibit human aggression the way the Tsavo Man-Eaters did. There are a handful of theories as to why this particular pair of cats acquired this unfortunate habit.

One possibility is the outbreak of a cattle plague in 1898 that greatly diminished the population of the lions’ usual prey, leading them to look for alternate sources of food. Another popular theory is that lions known as The Ghost and The Darkness may have become accustomed to finding human corpses in the Tsavo River crossing, as caravans from the East African slave trade would regularly move through the region.

It has also been suggested that one of the lions may have had a damaged tooth, affecting its ability to hunt its regular game and therefore leading it to turn to humans as an alternative. For a long time, this theory wasn’t largely entertained. Patterson himself even denied it, claiming he was the one to damage the lion’s tooth one night when the creature tried to charge at him.

Jeffrey Jung/Wikimedia CommonsThe skulls of the Tsavo lions now sit on display at Chicago’s Field Museum.

However, a 2017 study published in Scientific Reports found that one of the lions did indeed have an infection in his canine tooth.

This infection would have made it difficult for the lion to hunt his typical prey, as the creatures use their jaws to grab and suffocate animals like zebras and wildebeests. This could have caused the lion to turn to prey that was easier to catch, such as humans, who are slower and more defenseless against an attack.

No matter the true cause of the Tsavo lions’ behavior, their legacy — and the story of Patterson’s bold actions — lives on.

After learning about the man-eating Tsavo lions called The Ghost and The Darkness, read about Captain Jack Bonavita, the fearless one-armed lion tamer. Then, go inside the bloody story of venationes, the staged animal hunts of ancient Rome.