Over a 12-day period in July 1916, four people were killed and a teenage boy was severely injured by shark attacks in New Jersey that caused these sea creatures to forever be thought of as vicious "man-eaters."

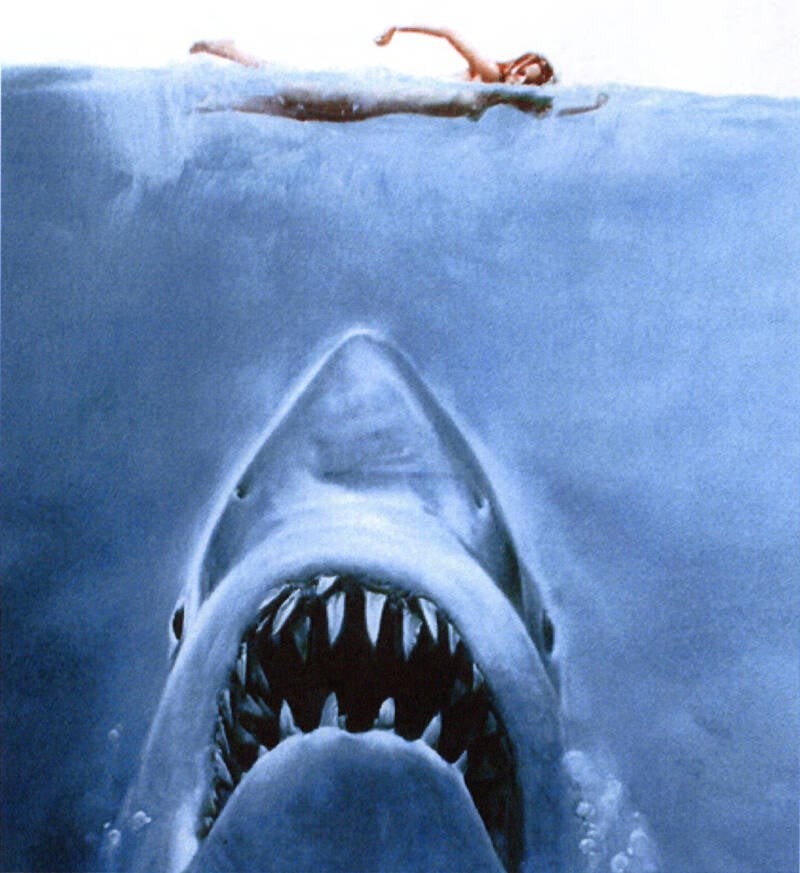

Public DomainThe shark attacks that gripped the Jersey Shore in 1916 were eerily similar to the events described in Jaws, and Peter Benchley may have been inspired by the tragedy when he wrote the novel nearly 60 years later.

The 1916 shark attacks on the Jersey Shore left four people dead, a teenager critically injured, and the entire nation in fear of “man-eaters.” The string of tragedies began on July 1 and came to an end 11 days later, but its impact on the public perception of sharks and the portrayal of the creatures in the media continues to this day.

Before the attacks, some experts were skeptical that sharks posed a danger to humans at all. Even after the first death on July 1, local government officials downplayed the severity of the situation, insisting that the beaches of New Jersey were perfectly safe. After the second attack, however, people began to panic.

Hotels and other businesses along the Jersey Shore lost millions of dollars in tourist revenue as people canceled their vacations in fear of becoming the next victim. The 1916 shark attacks also spawned a massive hunt, with New Jersey’s governor offering bounties to fishermen who caught and slaughtered sharks.

Some people believe the deadly event may have even inspired Peter Benchley to publish Jaws in 1974. The subsequent film adaptation perpetuated the image of sharks as bloodthirsty killers with a taste for human flesh — an image marine biologists have now been trying to shake for over a century.

The Beginning Of The 1916 Shark Attacks At The Jersey Shore

Before the 1916 shark attacks, scientists largely believed that sharks were little more than large, unintelligent fish with big teeth. They assumed that the sea creatures wouldn’t intentionally come close to humans — and they certainly wouldn’t bite a person.

Kmusser/Wikimedia CommonsA map of New Jersey showing the locations of the five 1916 shark attacks.

A millionaire businessman named Hermann Oelrichs was so convinced that sharks were harmless that he dove into the water with one in 1891, and he even offered a $500 reward to anyone who could provide proof of a shark attacking a human, according to the Florida Museum of Natural History. At the time of Oelrichs’ death in 1906, the prize remained unclaimed — but a decade later, beachgoers in New Jersey bore horrified witness to the grisly proof that Oelrichs had sought.

The summer of 1916 was an unusual one. It was hotter than average in New Jersey and in an era before air conditioning, no less. A polio epidemic was also ravaging New York City, sending people to East Coast beaches in droves to escape the illness and seek healing and restoration.

But the heat made for some unusually high water temperatures that year, too — and experts today theorize that those warm waters attracted sharks to the northern Atlantic to hunt.

Charles Vansant, a 25-year-old man from Philadelphia, was vacationing with his family in Beach Haven, New Jersey, on July 1, 1916. That evening, he decided to take a swim in the ocean before dinner. There was a dog playing on the beach, and Vansant was calling to it as he swam just beyond the surf. Then, Vansant’s joyful shouts turned to screams of terror.

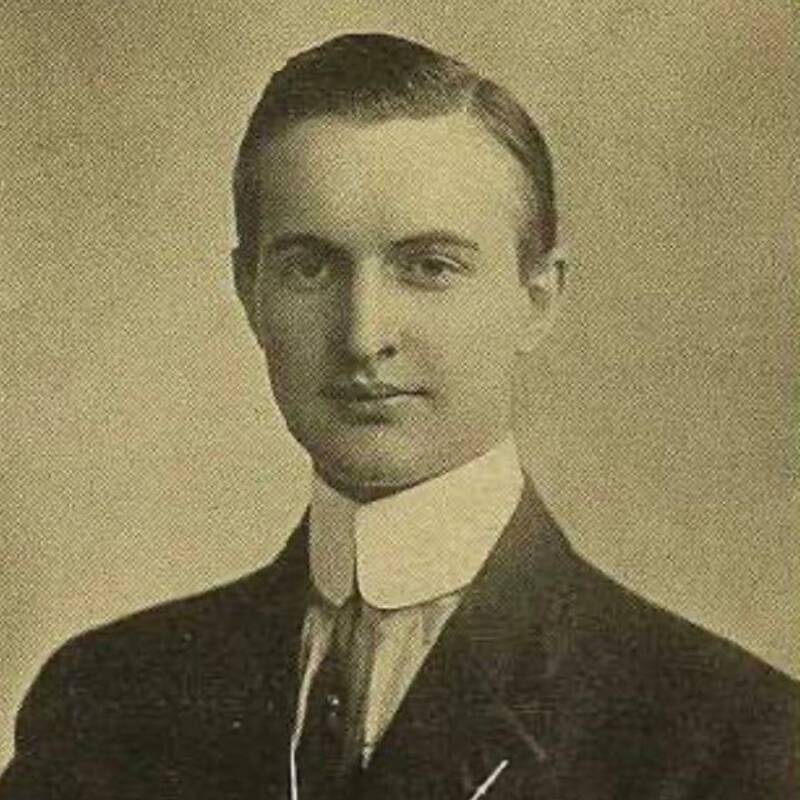

Find a GraveCharles Vansant, the first victim of the 1916 shark attacks at the Jersey Shore.

A lifeguard and a bystander rushed into the waves and pulled Vansant from the water. The flesh had been stripped from the back of his right thigh, exposing the bone from hip to knee. The men took Vansant into the Engleside Hotel to await an ambulance, but he bled to death on the manager’s desk before medics could arrive.

Despite the gruesome nature of Vansant’s death, local officials declared that swimmers had nothing to worry about, even as fishermen reported spotting sharks off the coast. For the next week, it indeed seemed as if the attack may have been a freak incident — but then a shark struck again.

The Disturbing Death Of Charles Bruder

On July 6, 27-year-old Charles Bruder, a bellhop at the Essex and Sussex Hotel in Spring Lake, New Jersey — located 45 miles north of Beach Haven — was swimming over 100 yards from shore when he became the second victim of the 1916 shark attacks.

The New York Times reported at the time: “As the life guards drew near him the water about the man was suddenly tinged with red and he shrieked loudly… [W]omen fainted at the sight. As the life guards reached for the swimmer he cried out that a shark had bitten him and then fainted.”

The article continued, “They dragged him into the boat and discovered that his left leg had been bitten off above the knee and the right leg just below the knee.” Bruder died on the way to shore.

Jerome Paillet/Wikimedia Commons; Olga Ernst/Wikimedia CommonsModern experts are in disagreement over whether the 1916 shark attacks were carried out by a bull shark (left) or great white shark (right).

News traveled quickly up and down the Jersey Shore. Beachgoers panicked, and vacationers began canceling their hotel stays. Some resorts installed wire mesh nets in the ocean to provide safe swimming areas for their guests, but despite these precautions, the second attack was the nail in the coffin for the summer tourist season.

Still, some officials remained convinced that Vansant and Bruder hadn’t been killed by sharks. “At least one newspaper attributed it to sea turtles, which of course nothing could be further from the truth,” Florida Museum of Natural History ichthyologist George Burgess stated. “That’s how adamant they were that it couldn’t be sharks.”

Dr. William G. Schauffler would become the voice of reason. As one of New Jersey’s most respected medical doctors, he stated unequivocally, “There is not the slightest doubt that a man-eating shark inflicted the injuries,” per the 1963 book Shadows in the Sea. This voice, though, would be lost in a sea of naysayers.

Then, there were two more fatal attacks. On July 12, 1916, what was assumed to be a single shark killed two people and left a third severely injured.

The Matawan Creek Shark Attacks Of 1916

Everything was quiet in the town of Matawan despite the hysteria raging closer to the ocean. It was 11 miles inland and nowhere near the beach. No one had ever seen large sharks in the muddy waters of Matawan Creek.

On the morning of the attacks, Captain Thomas Cottrell spotted a menacing form swim under a drawbridge in Matawan. He had heard about the deaths on the beaches, and he immediately began to alert the townspeople about what he had seen.

Rich Romano/Wikimedia CommonsA shark mural marks a location near the 1916 shark attacks in New Jersey’s Matawan Creek.

No one believed him, and many people even laughed at his story. The residents of Matawan didn’t think that a “man-eating” shark would ever come so far inland.

As Cottrell ran through the town, 11-year-old Lester Stillwell and four of his friends headed to Wyckoff Dock on Matawan Creek to go for a swim and cool off in the heat of the afternoon. Then, tragedy struck.

Shadows in the Sea describes the attack in gory detail. The boys were floating in the water when one of them felt what he thought was a large fish run into his leg. Then, Lester began to scream. “In an instant, it all but closed its jaws about Lester’s slim body and dragged him beneath the reddening waters of Matawan Creek. Lester had neither time nor life to scream again.”

Lester’s friends rushed into town for help. Everyone raced to the creek to see what had happened, and 24-year-old Stanley Fisher dove into the water to look for the boy. Almost immediately, he was bitten in the leg. He died at the hospital later that evening.

Asbury Park PressA newspaper headline from July 14, 1916, about the attacks at Matawan Creek.

Just 30 minutes after Fisher was attacked, 14-year-old Joseph Dunn was swimming half a mile up Matawan Creek. Someone ran up to the bank to warn the boy and his friends about the incident that had just occurred at Wyckoff Dock, and they hurried out of the water. Joseph was the last to reach the dock — and just as he was about to climb up the ladder, something “that felt like a big pair of scissors” grabbed his leg.

“I felt my leg going down the shark’s throat,” Joseph recalled. “I believe it would have swallowed me.”

Thankfully, Joseph’s older brother and his friends were able to wrest Joseph away from the creature. The boy’s leg was mangled, but he was alive. He was the only survivor of the 1916 shark attacks.

The Jersey Shore Shark Attacks Come To An End

After the July 12, 1916 shark attacks at Matawan Creek, total hysteria broke out not only in New Jersey but nationwide. President Woodrow Wilson called a meeting with his Cabinet to discuss the incidents, and the White House agreed to give federal aid to “drive away all the ferocious man-eating sharks which have been making prey of bathers.”

Captains of ships that moved in and out of New Jersey and New York were on high alert. Some reported schools of large sharks moving through the area. Fishermen headed into the ocean armed with rifles, harpoon guns, and axes. They used sheep guts to lure sharks to their boats and then slaughtered them.

Public DomainA woman points a gun into Matawan Creek as men in a canoe search for the shark behind the deadly attacks of July 12, 1916.

There were even rewards offered for anyone who killed man-eating sharks. This marked the beginning of the ferocious — and mostly unwarranted — reputation that sharks still have to this day.

The hunt for what the papers dubbed the “Jersey man-eater” spread up and down the East Coast. It has since been hailed “the largest scale animal hunt in history.”

On July 14, Michael Schleisser caught a seven-and-a-half-foot long, 325-pound shark in Raritan Bay near Matawan Creek. When the creature’s stomach was cut open, it reportedly contained human bones and flesh. At the time, it was identified as a young great white shark.

Though no one can be sure it was the same shark that killed the swimmers in Matawan Creek or the men in Beach Haven and Spring Lake — or even if the same shark was responsible for all five attacks — the shark attacks of 1916 came to an end.

Public DomainMichael Schleisser poses with the shark he caught in Raritan Bay, which may have been the fish responsible for some or all of the 1916 shark attacks.

Perhaps this lone shark did kill four people and wound another. Shark science was in its infancy back in 1916. No one knows precisely what happened, and today, we can only speculate.

Modern experts believe the shark (or sharks) responsible for the attacks may have been a sick or injured bull shark or great white simply looking for food. Rarely does a lone shark drift a dozen miles inland along a creek, save for bull sharks, which can and do swim inland in search of a meal. It could be that scientists in 1916 mistook the “young great white” for a bull shark.

While we may never know what species was responsible for the 1916 shark attacks or why exactly they happened, one thing is certain: They marked the beginning of shark hysteria as we know it today.

After learning about the 1916 shark attacks along the Jersey Shore, read about the megalodon, the prehistoric shark that grew up to 60 feet long. Then, meet the mako shark, the deadly “cheetah of the ocean.”