Measuring up to 13 feet long and weighing at least 1,200 pounds, the shortfin mako shark is a formidable predator in oceans all over the world.

The great white shark has arguably taken the spotlight away from other sharks. But while it is viewed as an expert predator, and often, incorrectly, as a mindless killing machine, the great white is not the most agile of sharks. That honor belongs to the shortfin mako shark, which may, in fact, be one of the most efficient hunters in the entire ocean.

Capable of swimming as fast as 80 miles per hour, the mako shark is not only known for its incredible speed but also for its leaping ability. These skills — along with its knife-like teeth — make the mako shark a formidable carnivore. But although these animals have no known natural predators, they are sadly endangered, and humans are largely to blame for that.

This is the true story of the mako shark — and how one of the deadliest creatures in the sea became one of the most threatened.

What Is A Mako Shark?

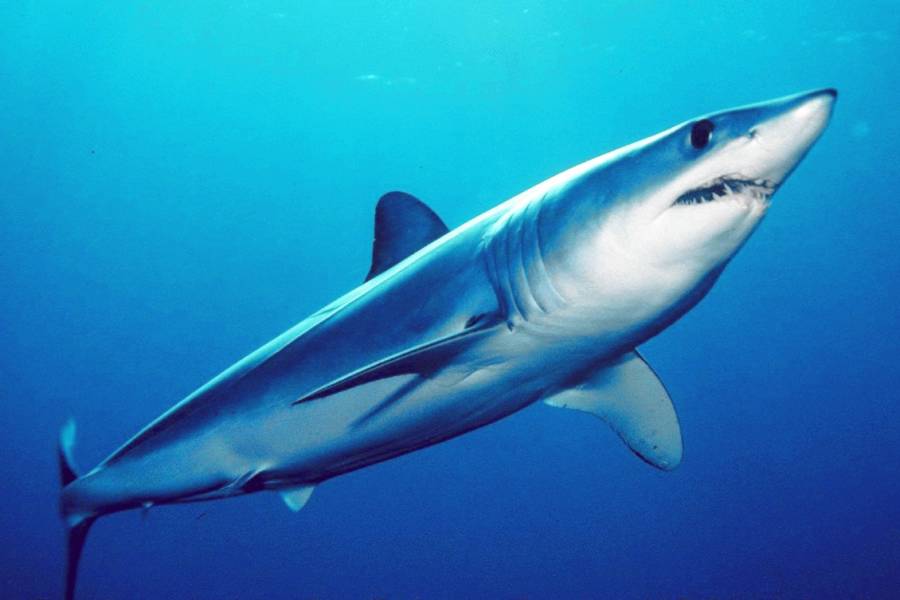

Wikimedia CommonsThe shortfin mako shark is also known as the blue pointer and the bonito shark.

Like the famous great white, the mako shark belongs to the mackerel family of sharks. Interestingly enough, the generic name “mako” actually refers to two different species of shark: the shortfin and the longfin mako.

Usually, reports about mako sharks refer to the shortfin mako. The lesser-known longfin mako is an uncommon species. And due to its long, broad pectoral fins, it does not exhibit the speed of the shortfin mako.

Both longfin and shortfin mako sharks grow to an average of 10 feet long. But some of the longest shortfin mako sharks can grow to be up to 13 feet as adults, according to Ocean Conservancy. These animals usually weigh around 1,200 pounds. And despite their large size, they also boast a stunning leaping ability that allows them to jump about 30 feet out of the water.

The name “mako” comes from the Indigenous Māori people of New Zealand, and the word simply translates to “shark” in the Māori language. Viewed as guardian spirits by the Māori, sharks are featured in several traditional Māori myths. The teeth of mako sharks have also been high-prized among the Māori for use in necklaces, earrings, and trade throughout history.

Wikimedia CommonsThe teeth of a shortfin mako shark have often been compared to knives.

But these animals aren’t only found in the New Zealand area. Both the shortfin and longfin mako sharks have been spotted worldwide from Californian to Argentinian waters to the South Pacific. The shortfin mako is found primarily in offshore temperate and tropical seas, while the longfin mako is found in the Gulf Stream and warmer offshore waters.

Ultimately, it’s the shortfin mako’s speed that distinguishes it from other sharks. Though a typical mako moves at 31 miles per hour with “bursts” of 46 miles per hour, they are capable of reaching speeds up to 80 miles per hour, according to Science Daily. This makes it the world’s fastest shark.

“I’d compare a mako to something like a cheetah, but bigger and with larger teeth and more muscle,” explained Nick Wegner of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego, in an interview with Discovery.

This comparison is quite literal when it comes to how fast the “cheetah of the ocean” moves. Swimming up to 80 miles per hour, the shortfin mako approaches the top speed of the cheetah. And just like the cheetah, it seems as though the mako shark was quite literally built for speed.

The Scary And Fascinating Science Behind The “Cheetah Of The Ocean”

Southwest Fisheries Science Center/NOAA Fisheries ServiceThanks to its speed, the shortfin mako is arguably even more fearsome than the great white.

Over millions of years of evolution, the shortfin mako has developed specific adaptations, giving it an edge over all other sharks. With a conical snout like a bullet, small pectoral and dorsal fins, and a slim, but muscular streamlined body, the shortfin mako is essentially built like a torpedo. This is fortunate, as its principal food sources are the agile bluefin tuna and the swordfish.

In fact, researchers have found the shortfin mako has adopted a similar muscular structure to the bluefin tuna. In a process called convergent evolution, prey and predator develop similar physical traits over time.

Unlike most fish, the bluefin tuna and the shortfin mako have a centralized muscle structure located close to their backbone, which acts as pistons that propel both fish forward. In comparison, other fish rely on muscles that run down both sides of their bodies to aid them in continuous movement.

This piston-like thrust is aided further by the crescent-shaped tail of the shortfin mako, which helps propel the fish forward as it swims.

Wikimedia CommonsMako sharks are said to swim in a menacing figure-eight pattern just before they attack their prey.

Remarkably, the shortfin mako shark is also able to swim long distances, traveling up to 60 miles per day, according to NSU Florida. Most species that can sprint over short distances lack the endurance for long distances.

Its muscles have adapted to take in oxygen to recover in half the time as other sharks. It can also contract heat into body organs and muscles, which increases performance and makes it partially warm-blooded. This trait is shared by both the shortfin mako and the great white shark.

All of these fascinating — and terrifying — features may make you wonder whether the mako would ever prey on a human who’s sailing in offshore waters. Though the mako shark primarily feeds on prey like swordfish and tuna (along with bluefish and marine mammals), it’s also been known to attack people, especially if it’s provoked or caught on a fishing line.

You might take comfort in the fact that shortfin mako sharks have only been linked to nine unprovoked attacks on people since 1580, according to the Florida Museum of Natural History. But on the flip side, humans have proven to be very dangerous to mako sharks, largely thanks to overfishing.

How Mako Sharks Became Endangered — And What Experts Are Doing To Help

Marrajos/Flickr/Wikimedia CommonsDead shortfin mako sharks at the fishing port of Vigo, Galicia, Spain.

Besides speed, the mako shark has another (tragic) fact in common with the cheetah: Its population is currently threatened. And sadly, mako sharks are even more vulnerable, as they’re currently listed as endangered.

Commercial fisheries often target it for food, leathers, and oils. The animal is also sometimes used for the controversial delicacy of shark fin soup, which usually involves finning sharks alive, rendering them immobile, and then allowing them to sink to the bottom of the ocean to suffocate.

Sometimes, casual fishermen even hunt the mako shark simply for the bragging rights of catching the fearsome fish.

But despite the mako shark’s endangered status, conservationists, activists, and government authorities are putting forth efforts to save the species.

In the United States, NOAA Fisheries has implemented numerous regulations since 2017 to address the overfishing of mako sharks, including requiring special permits to harvest them. They’ve also recommended special fishing gear to other fishermen to prevent accidental bycatch of the animals.

And in 2021, the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas launched a two-year ban on the retaining, shipping, and landing of the North Atlantic shortfin mako shark to give the species some time to recover.

Hopefully, the shark will soon thrive in the waters of the world once again.

After reading about the mako shark, discover 15 great white shark facts that will shatter your assumptions about the famous animal. Then, take a look at the Greenland shark, the world’s longest-living vertebrate, or learn about the fear of the ocean known as thalassophobia.