Perhaps the most dignified stagecoach robber of the Old West, Black Bart earned the nickname the "gentleman bandit" because of his well-mannered demeanor, his reputation for never firing a shot, and his peculiar habit of leaving poems behind at his crime scenes.

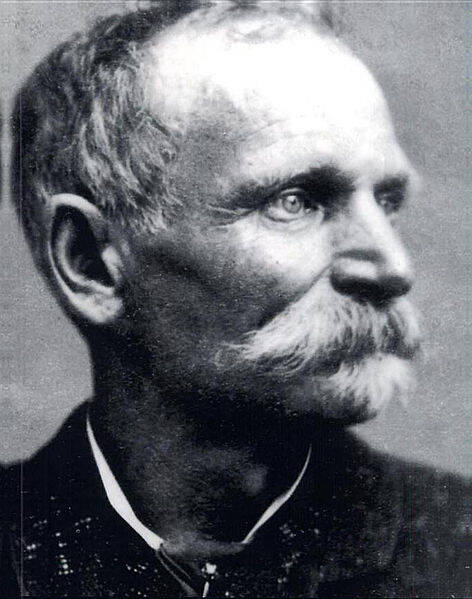

Wikimedia CommonsCharles Boles, aka “Black Bart,” the 19th-century stagecoach robber.

Between 1875 and 1883, an outlaw named Black Bart committed at least 28 stagecoach robberies along the West Coast — and his polite demeanor and habit of leaving clever poems at the scenes of his robberies earned him a reputation as the “gentleman bandit.”

Also known as Charles Boles, Black Bart had had a turbulent life before turning to crime. He joined the California Gold Rush in 1849, but was unsuccessful. Boles eventually abandoned mining and settled in Illinois, where he married and raised a family. When the U.S. Civil War broke out, he enlisted and fought in several key battles before returning to civilian life.

In the end, it was a land dispute with Wells Fargo that led him to a life of crime. Believing the company had slighted him, Boles swore revenge, orchestrating a series of stagecoach robberies in California and Oregon and making a name for himself as an unusually gentlemanly Wild West bandit in the process.

Black Bart’s career came to an end in 1883 when he dropped a handkerchief that helped detectives track him down. He was arrested and sent to prison. But shortly after his release, Boles vanished from the historical record — and to this day, no one knows for sure what became of him.

This is the story of Black Bart, the most poetic outlaw of the American West.

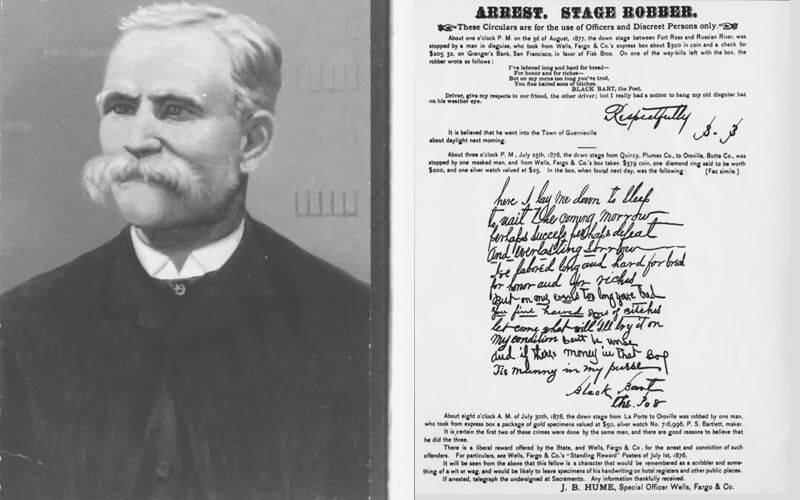

Public DomainBlack Bart alongside his legendary poetry.

Who Was The Infamous Black Bart — And Why Did He Pursue A Life Of Crime?

Black Bart was born Charles Bowles (or Charles Boles) in 1829. Some say he emigrated from England when he was young, while others say he was born in New York. Like much of Boles’ life, the details are murky.

As a child, Boles was a strong athlete who excelled at wrestling. Calaveras History reports he suffered a bout of smallpox in his youth, but survived.

As he grew older, Boles began looking to make a name for himself and soon found himself drawn West during the California Gold Rush in 1849. Unfortunately, he never struck it rich panning for gold, despite many years of trying.

Boles eventually decided to abandon his gold rush dreams and settle down in Illinois. There, he married a woman named Mary Elizabeth Johnson. The two lived seemingly normal lives, raising their four children in Decatur, Illinois.

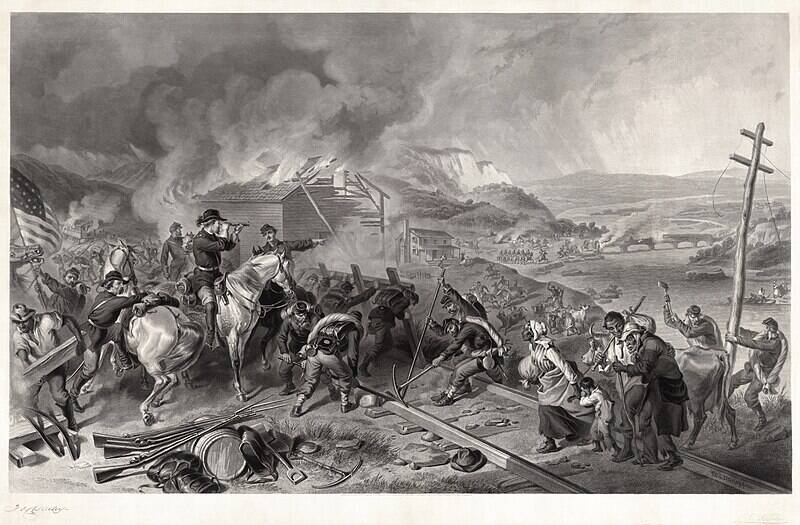

That all changed with the outbreak of the U.S. Civil War in 1861. Boles enlisted as a private in Company B, 116th Illinois Regiment, fighting in the Battle of Vicksburg and even participating in Sherman’s March to the Sea. He was discharged on June 7, 1865, two months after the Civil War ended.

Public DomainAn illustration of General Sherman’s March to the Sea, an event Black Bart participated in.

Boles returned home and settled into a life of farming, but soon grew restless. By 1867, he had once again set out to pursue a life of prospecting, traveling to Montana and Idaho in search of gold. Instead, he only found trouble.

After he purchased a share of a mine in Montana, it drew the attention of Wells Fargo & Company. When Boles refused to sell it to them, the company reportedly cut off his water supply, forcing him to abandon the mine. Enraged, Boles wrote to his wife spouting ideas of revenge. This was the last time she would hear from her husband until his arrest years later.

In 1875, Boles began enacting his revenge on Wells Fargo, robbing the company’s stagecoaches that ran up and down the West Coast. Before long, he assumed a moniker he’d purportedly found in an adventure story about a fictional robber: “Black Bart.”

The Gentleman Bandit Begins Robbing Stagecoaches Across The Wild West

Black Bart’s first robbery occurred on July 26, 1875. After apprehending a Wells Fargo stagecoach in Calaveras County, California, he made off with almost $200 — and gained the confidence to stage 27 more holdups.

Charles Boles’ robberies were simple. He would lie in wait for a stagecoach to pass, and then jump out with a shotgun in hand. When the driver stopped, Boles would politely demand all of the cash and valuables on board.

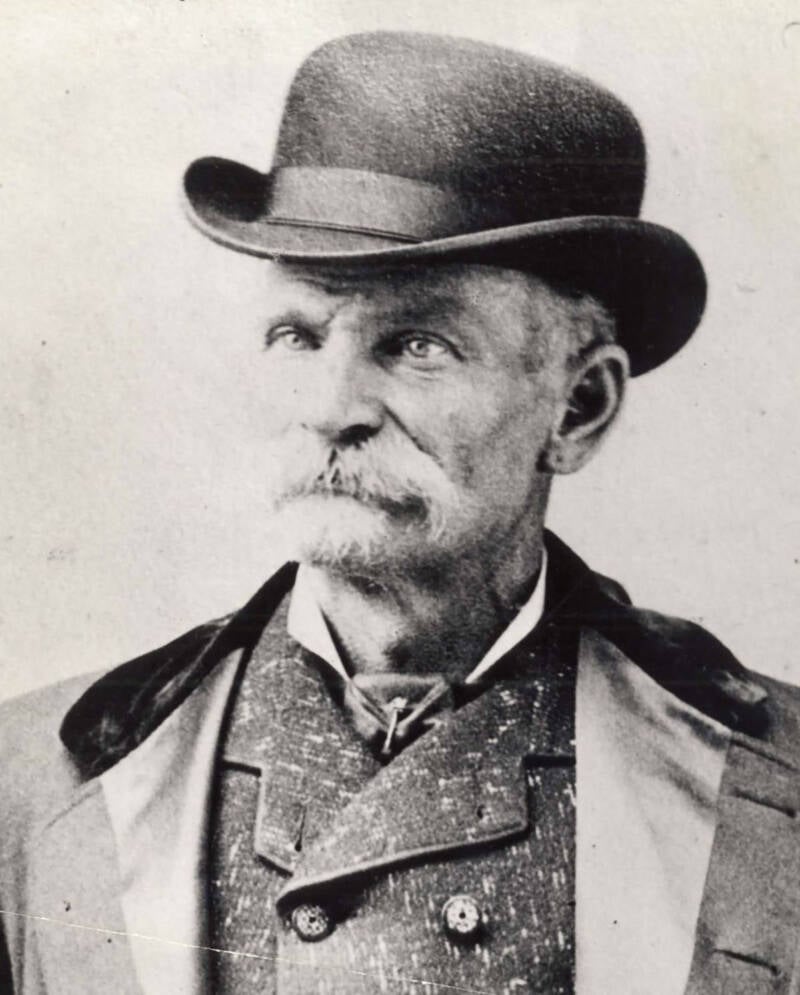

Public DomainBlack Bart was unusually well dressed, reportedly wearing a bowler cap during robberies and a gold-handled cane and diamond ring in his day-to-day life.

Where other Old West stagecoach robbers were often crude and violent, Boles was well-mannered. He traveled on foot, worked alone, and never fired a shot. He said “please” and “thank you” during holdups and was unfailingly polite to women. Because of this dignified demeanor, he soon earned the nickname the “gentleman bandit.”

Of course, Black Bart was best known for his tendency to compose poetry, which he sometimes left behind at his crime scenes.

On July 25, 1878, he apprehended a Wells Fargo stagecoach traveling the long road between Quincy and Oroville, California. He made off with nearly $400, a passenger’s diamond ring, and a silver watch, according to George Hoeper’s 1995 book Black Bart: Boulevardier Bandit. Afterward, he left this poem behind at the scene of the holdup:

“Here I lay me down to sleep

To wait the coming morrow,

Perhaps success, perhaps defeat,

And everlasting sorrow.

Let come what will, I’ll try it on,

My condition can’t be worse;

And if there’s money in that box

‘Tis munny in my purse.”

A message from another robbery read:

“I’ve labored long and hard for bread,

For honor, and for riches,

But on my corns too long you’ve tread,

You fine-haired sons of b*tches.”

Black Bart was also unusually well dressed, donning a bowler cap during robberies as well as a flour sack over his face with two holes cut out for his eyes. Far from an outdoorsman, Boles preferred city life in San Francisco, where he reportedly donned a diamond ring and a gold-handled cane in his day-to-day life.

Unfortunately, it was this fondness for fine clothing that ultimately brought his career to an end.

The End Of Black Bart And His Mysterious Disappearance From The Historical Record

Haddonfield Police Department/Facebook Charles Boles’ home in Decatur, Illinois.

In the end, it was a piece of clothing that landed Black Bart behind bars.

After fleeing his last robbery on Nov. 3, 1883, Black Bart dropped a handkerchief bearing a marking from a laundry in San Francisco. Detectives were able to connect it to him, and he was taken into custody in 1883.

Throughout the trial, Boles claimed that he did not commit any robberies after 1879, perhaps mistakenly believing that the statute of limitations would protect him from prosecution. Still, he was ultimately found guilty of just one robbery and sentenced to only six years in prison. True to form, he was released for good behavior after four.

Upon his 1888 release, reporters asked Boles if he would go back to robbing stagecoaches. He replied, “No, gentlemen. I’m through with crime.” When they asked him if he planned to write more poetry, he said, laughing: “Now, didn’t you hear me say that I am through with crime?”

Shortly after, he checked into a hotel in Visalia, California — and vanished. He was last seen at the hotel on Feb. 28, 1888.

No one is quite sure what happened to Black Bart next. Some say he fled the country, and others suggest that he died years later after living a quiet life out East. A newspaper obituary from New York mentions a Civil War veteran named Charles Boles. If it truly referred to Black Bart, he would have died at 87 or 88 years old.

Given the various conflicting accounts about his life, most of the facts surrounding Charles Boles’ story are muddled. It’s hard to say for certain how much of it is true, and how much was dreamt up by newspapers.

But whatever his fate, Black Bart was the kind of criminal who inspired curiosity, admiration, and more than a few myths. Even during his lifetime, he was truly one of the most legendary figures of the Old West.

After reading about Black Bart, the gentleman bandit of the American frontier, learn how Billy the Kid went from New York City boy to Wild West legend. Then, check out these photos of what life was really like in the Wild West.