The photographer behind "The Vulture and the Little Girl," depicting a starving child during Sudan's 1993 famine, Kevin Carter killed himself the following year.

Warning: This article contains graphic descriptions and/or images of violent, disturbing, or otherwise potentially distressing events.

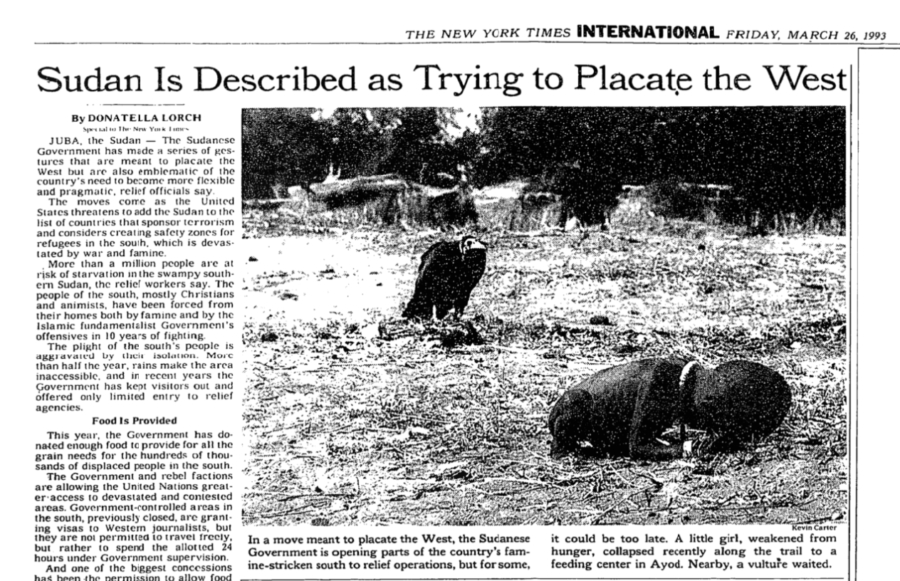

Kevin Carter/Wikimedia CommonsKevin Carter’s most famous photo, “The Vulture And The Little Girl,” captured during the 1993 famine in Sudan.

Kevin Carter, a photojournalist who captured the horrors of apartheid in South Africa, is best known for his 1993 photo of the Sudanese famine, “The Vulture and the Little Girl.” However, his legacy extends far beyond this Pulitzer Prize-winning image.

Kevin Carter’s work led to debates about the ethics of photojournalism. Where was the line between reporting on a situation and intervening to help those in need? Critics claimed Carter was inhumane and that he should have dropped his camera to run to the aid of the child he’d photographed. But at the same time, the image he captured helped reveal the reality of the situation in Sudan to the outside world, leading to more aid for the country.

Still, he was consumed by guilt and trauma. He was haunted by what he’d seen and photographed in South Africa, Sudan, and beyond, and he suffered from depression in the months following the publication of the photo.

In the end, Kevin Carter was unable to move past his internal ethical dilemmas and personal struggles. He died by suicide on July 27, 1994, just a year after taking “The Vulture And The Little Girl,” the photograph that won him the Pulitzer Prize, but his impact on photojournalism has not been forgotten.

- How Kevin Carter’s Early Life Inspired His Photojournalism

- The Bang-Bang Club And The Horrors Of Apartheid-Era South Africa

- The Story Behind Kevin Carter’s Controversial Photo, “The Vulture And The Little Girl”

- The Fame, Guilt, And Moral Dilemmas That Followed Carter’s Prize-Winning Photograph

- The Devastating Suicide Of Kevin Carter

How Kevin Carter’s Early Life Inspired His Photojournalism

Kevin Carter was born in Johannesburg, South Africa, on September 13, 1960, in the midst of apartheid. From a young age, he was appalled by the racial segregation and violence he witnessed around him on a daily basis.

Carter initially planned to become a pharmacist, but he had to drop out of school after he was drafted into the South African Army. He decided to enlist in the Air Force instead, and he soon discovered that racism was just as rife in the military as it was in the civilian world. While defending a Black mess hall employee from insults in 1980, Carter was badly beaten by his fellow servicemen.

YouTubeA Pulitzer Prize winner and part of the “Bang-Bang Club” of photojournalists in South Africa, Kevin Carter died by suicide following his work during Sudan’s 1993 famine.

He deserted his post for a time following the incident, but he ultimately returned to finish out his required service, and he was on guard duty at the Air Force headquarters in Pretoria during the Church Street bombing of May 20, 1983. The attack killed 19 people, and the grisly scene inspired Carter to become a photojournalist and expose the brutality of apartheid to the world.

So, after leaving the Air Force later that year, Carter took a job at a camera supply store and began making contacts in the world of journalism. He first worked as a sports photographer for the Johannesburg Sunday Express and then moved on to capturing gritty images of apartheid-era violence for the Johannesburg Star.

By 1990, he was part of the Bang-Bang Club, a group of four conflict photographers who traveled through South Africa documenting the brutal attacks that continued even as the apartheid system officially came to an end.

The Bang-Bang Club And The Horrors Of Apartheid-Era South Africa

The Bang-Bang Club consisted of Kevin Carter, Greg Marinovich, Ken Oosterbroek, and João Silva. The name was born from an article in a South African newspaper and referred to the violence that the men put their lives on the line to document.

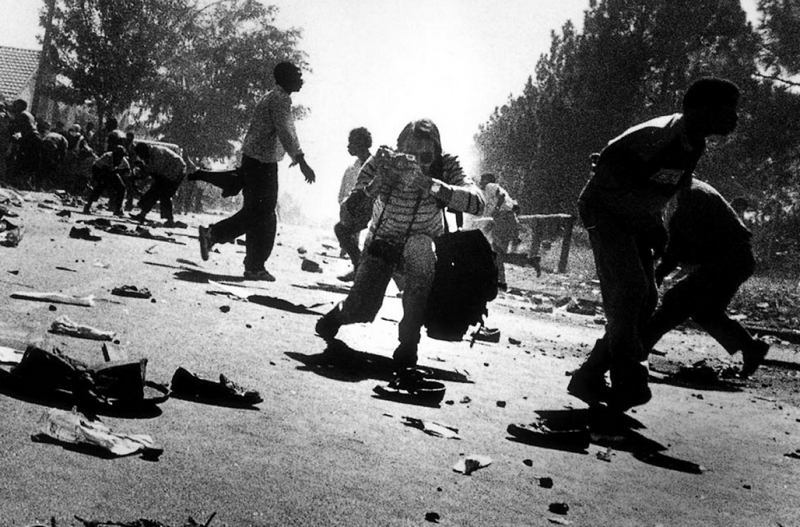

Indeed, their work was dangerous. The four photographers weren’t afraid to step right into the action to get the best shot if it meant revealing the reality of life in South African townships to a wider audience.

Carter and his colleagues witnessed vicious political unrest, protests, and bloody clashes between apartheid supporters and anti-apartheid “comrades.” In the mid-1980s, Carter became the first person to photograph the violent “necklacing” execution method in which a tire filled with gasoline is placed around a victim’s neck and lit on fire.

Paul Weinberg/Wikimedia CommonsKevin Carter and the Bang-Bang Club captured the violence that gripped South Africa in the 1980s and ’90s.

As Harold Evans reported in an essay titled “Reporting in the Time of Conflict” for the Newseum, Kevin Carter later explained the ethical dilemma he’d faced while documenting the incident. “I was appalled at what they were doing,” he said. “I was appalled at what I was doing. But then people started talking about those pictures… then I felt that maybe my actions hadn’t been at all bad. Being a witness to something this horrible wasn’t necessarily such a bad thing to do.”

It wasn’t the last time Carter would question the ethics of his work, however. Many of those same feelings arose once more in 1993, when he traveled to South Sudan to report on the famine ravaging the country.

The Story Behind Kevin Carter’s Controversial Photo, “The Vulture And The Little Girl”

In March 1993, Carter was given the opportunity to document the famine that had been brought about by political unrest and civil war. He and João Silva traveled to the country and flew to the town of Ayod with a group that was providing food aid. There, they snapped photos of the masses of people who were starving to death, but the most poignant image Carter captured featured just one tiny subject.

In the photo, popularly known as “The Vulture and the Little Girl“, an emaciated child collapses in the dirt while trying to reach a nearby food center. A vulture looks on from several yards away, waiting for the youth to die so it can swoop in for a meal.

The image was first published in The New York Times on March 26, 1993, and it sparked an intense reaction. Hundreds of concerned readers called and wrote letters to the newspaper demanding to know the fate of the child. While some people praised Carter for capturing the moment and raising awareness of the harsh reality of the situation in Sudan, others criticized him for taking photos instead of helping.

“People were very quick to label Kevin Carter a vulture,” Dan Krauss, the director of the Oscar-nominated documentary The Death of Kevin Carter, told NPR in 2006, “but they didn’t take the opportunity to try to understand the complexity of the situation in the Sudan and the complexity of being a journalist faced with that degree of suffering.”

The New York Times“The Vulture and the Little Girl” as printed in The New York Times on March 26, 1993.

Indeed, the response to the photograph was so strong that The New York Times issued an update on March 30, stating, “The photographer reports that she recovered enough to resume her trek after the vulture was chased away. It is not known whether she reached the center.”

This answered some lingering questions, but many remained. Had Kevin Carter done anything to help the child?

Silva revealed to TIME in 1994 that Carter had watched the “little girl” (who was later revealed to be a boy named Kong Nyong) struggle for 20 minutes, waiting for the vulture to raise its wings so he could get the perfect shot. The bird never did, though, and Carter ultimately shooed it off.

“He was depressed afterward,” Silva said. “He kept saying he wanted to hug his daughter.”

In 2011, Kong’s father revealed that he had actually survived the famine but died from an illness much later, in 2007. Tragically, Carter would never learn of the child’s ultimate fate.

The Fame, Guilt, And Moral Dilemmas That Followed Carter’s Prize-Winning Photograph

Kevin Carter and the Bang-Bang Club witnessed the unthinkable on a daily basis, which naturally took a toll on them. However, Carter would never recover from the internal turmoil he experienced in the aftermath of his trip to Sudan.

Carter went through a roller coaster of emotions in the months that followed the publication of the photo. In April 1994, he was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for the image, a distinction that should have brought him pride. However, he instead felt guilt, shame, and sorrow that were only intensified by the backlash and ethical criticism the photograph received.

Ilagardien/Wikimedia CommonsPhotographer Rebecca Hearfield snapping a picture of Kevin Carter.

That very same month, his friend and fellow Bang-Bang Club member Ken Oosterbroek was shot and killed while on location. He was documenting a violent clash between the National Peacekeeping Force and the anti-apartheid African National Congress when the peacekeepers opened fire, fatally striking Oosterbroek and injuring Greg Marinovich.

Carter was being interviewed about his Pulitzer Prize at the time. He felt that he should have been with the group, and his survivor’s guilt was almost unbearable.

The following month, Nelson Mandela was elected the president of South Africa. Kevin Carter had built his life around exposing the evils of apartheid, and now, in a way, it was over. He didn’t know what to do. On top of that, he felt a need to live up to the Pulitzer he’d won. Soon after, in the fog of his depression, he made a terrible mistake.

The Devastating Suicide Of Kevin Carter

While on assignment for TIME in July 1994, Carter traveled to Mozambique. On the flight back to Johannesburg, he left all of his undeveloped film — some 16 rolls — on the plane. It was never recovered. For Carter, this was the last straw.

YouTubeKevin Carter shooting in the midst of conflict, doing what he did best.

Less than a week later, Carter was dead. On the night of July 27, he drove to a park, ran a garden hose from the exhaust pipe of his truck and into the window, and took his own life via carbon monoxide poisoning.

The note he left behind painted a painful image of the guilt and feelings of helplessness that had plagued him. “I am haunted by the vivid memories of killings & corpses & anger & pain… of starving or wounded children, of trigger-happy madmen, often police, of killer executioners,” Carter wrote.

He concluded, “I have gone to join Ken [Oosterbroek] if I am that lucky.”

Kevin Carter was just 33 years old. However, his short time on Earth left an indelible mark on humanity’s consciousness. “The Vulture and the Little Girl” spread awareness of the reality of life in parts of Africa in a way that no other photo had before.

Carter’s death also sparked discourse on ethics in photojournalism, challenging the standard for reporters to simply document without intervening. Conversation surrounding the psychological toll that conflict photography had on journalists expanded as well. In that way, Carter’s legacy survives far beyond the photo he’s best known for.

What Happened To The Child In Kevin Carter’s Famous Photo?

In 2011, the father of the child featured in “The Vulture and the Little Girl” revealed that the “little girl” was actually a boy named Kong Nyong. Kong didn’t die from starvation during the famine, but he passed away from an undisclosed illness in 2007.

Did Carter Ever Explain Why He Didn’t Help The Child?

While Carter did shoo the vulture away, he didn’t help Kong Nyong further because of journalistic guidelines at the time, which discouraged reporters and photographers from interfering in most situations. However, he was deeply affected by the experience.

Why Was Carter’s Photo Of Necklacing So Important?

Necklacing, a brutal execution method used during apartheid that involved placing a tire full of gasoline around a victim’s neck and igniting it, hadn’t been photographed before Carter documented it in the mid-1980s. His image brought global attention to the unfathomable violence occurring in South Africa.

Why Did Kevin Carter Take His Own Life?

Depression, survivor’s guilt, possible post-traumatic stress disorder, financial stress, and backlash from his work all contributed to Carter’s suicide. In the note he left behind, he said that he was “haunted” by the things he’d seen.

What Impact Did Kevin Carter’s Work Have On Photojournalism?

Carter’s work led to debate about ethics in photojournalism when it came to documenting the suffering of innocent people as well as where to draw the line between reporting and intervening. His death also drew attention to the trauma conflict photographers faced.

Where Can I See Carter’s Full Photo Collection?

Kevin Carter’s full collection is available to view in the Getty Images photo archives and The Bang-Bang Club book.

After reading about the life and death of Kevin Carter, look through more of the most influential photos in history. Then, see Mathew Brady’s groundbreaking photos of the American Civil War.

If you or someone you know is contemplating suicide, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 or use their 24/7 Lifeline Crisis Chat.