Starting with its first street gang in the early 1800s and continuing with its most recent mob boss assassination in March 2019, New York's history of gangs is as gruesome as it is complicated.

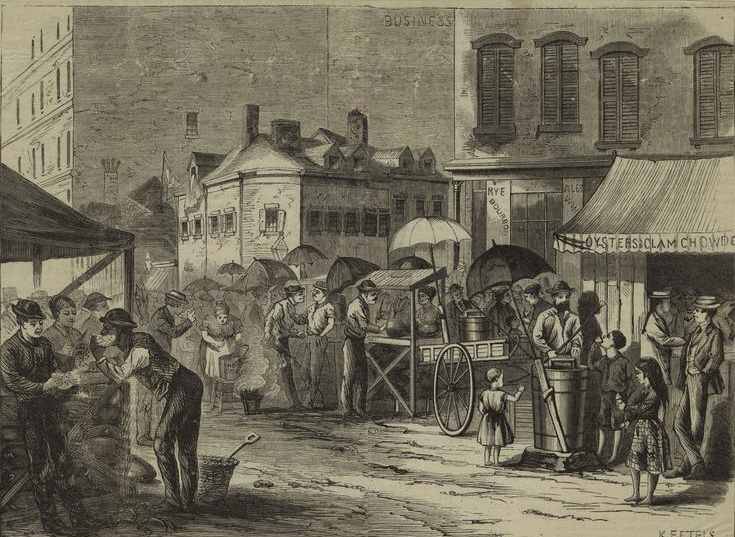

Public Domain19th-century depiction of the dilapidated Five Points neighborhood.

On March 13, 2019, Francesco “Franky Boy” Cali, the acting head of the notorious Gambino crime family, was shot and killed by unknown assailants outside of his Staten Island home. He was 53 years old.

A decade earlier, Cali had been arrested for racketeering and pleaded guilty to extortion charges. Few mobsters had rivaled his storied career in the New York underworld in recent years.

His murder marked the end of a dry spell in organized crime: It was New York’s first major mob boss killing in more than 30 years.

Cali’s death is a part of an expansive history of New York City crime that goes back to the city’s founding in the 17th century. Part of how the city made so much money in the first place was by serving as a hub for colonial pirates.

In this way, one could say New York was a city built on crime.

But the gang culture the city is famous for didn’t arise in until the turn of the 19th century. The gangs’ motivations had little to do with greed — at least at first. In fact, the rise of New York’s organized crime has roots in xenophobia, racism, and immigration.

Here’s the surprising story of how the Big Apple became a historical hub of organized crime.

The Bloody Birth Of New York Crime

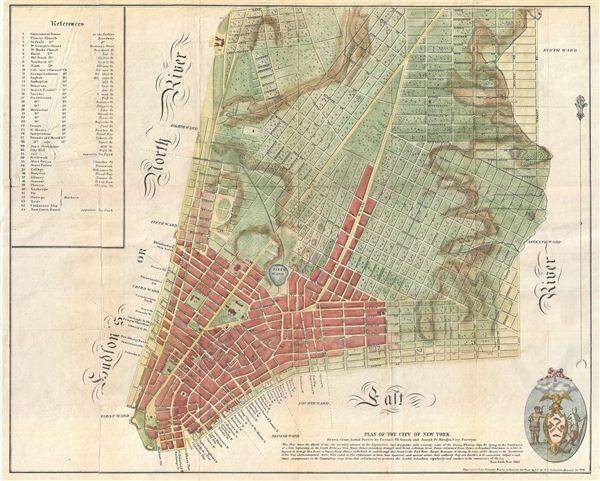

Wikimedia CommonsA map of the 1801 Mangin-Goerck plan for New York City.

Between 1790 and 1820, following the American Revolution, the population of New York City expanded from 33,131 to 123,706. By 1860, a quarter of its residents were Irish.

At the time, the most populated portions of the city were in what’s now lower Manhattan. And for most city dwellers — especially new arrivals from Europe and elsewhere — only a burgeoning slum was available to them.

One of the most challenging places to live in this time was Manhattan’s Five Points district. The region was marked for its lack of fresh water, its overcrowded and squalid conditions, and its abundance of disease.

New York’s first gangs seemed to have appeared as a community defense against this environment. Groups of young men would travel together to ward off potential thieves or attackers across the seedy district. In a sense, they were basically a vigilante community watch.

It wasn’t until 1825, however, that these groups all came together as one of the earliest-known gangs in the city called The Forty Thieves. Based out of a grocery store and a dive bar, the Thieves became the prototype for later New York City gangs.

Made up mostly of Irish immigrants, the Thieves were known to commit muggings and robberies as well as cater to corrupt politicians.

What set the Thieves apart from groups before it was its structure and organization. Unlike any other recorded criminal enterprise in New York City at that time, the Thieves had an acknowledged leader: Edward Coleman.

One of the downsides to having a leader, however, is that if the leader dies, then the gang risks falling apart and losing momentum.

That is exactly what happened to the Forty Thieves after Edward Coleman’s 1838 execution for the murder of his wife. He had the dubious “honor” of being the first man hung in New York City’s newly-opened Tombs prison.

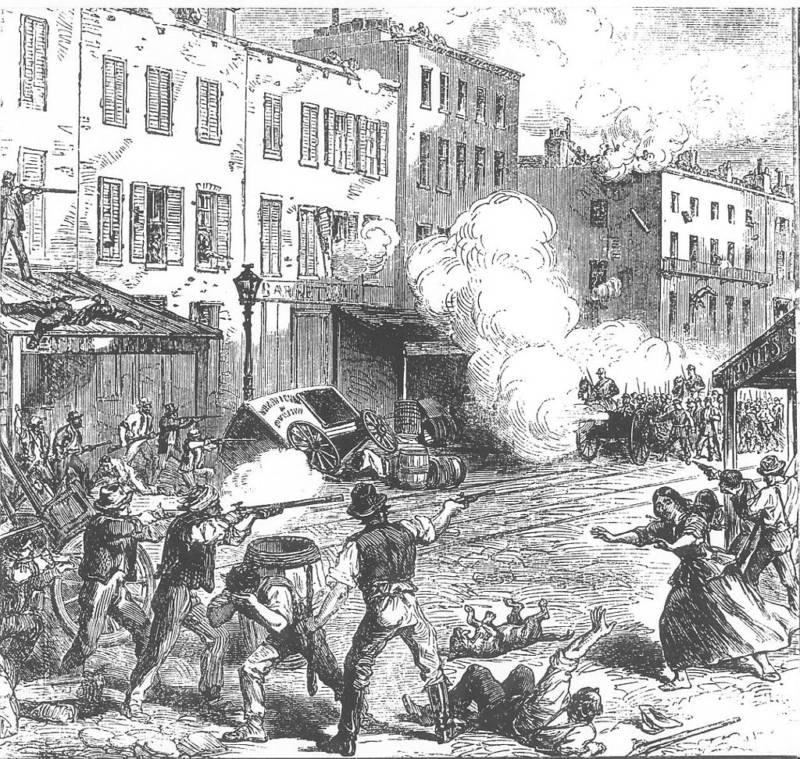

Wikimedia CommonsMany gangs, including both the Bowery Boys and the Dead Rabbits, clashed with police and Union Army troops during the 1863 New York City draft riots.

Although some members of the Forty Thieves stayed together, many of them splintered off into new groups by the 1850s. Others simply joined existing groups, like the Irish Catholic Dead Rabbits gang.

Each of these groups had their own unique rules and customs and catered to a growing schism in the city between native New Yorkers and immigrants. Indeed, the first gang wars were spurred by xenophobia.