The Gotti Era And The Lufthansa Heist

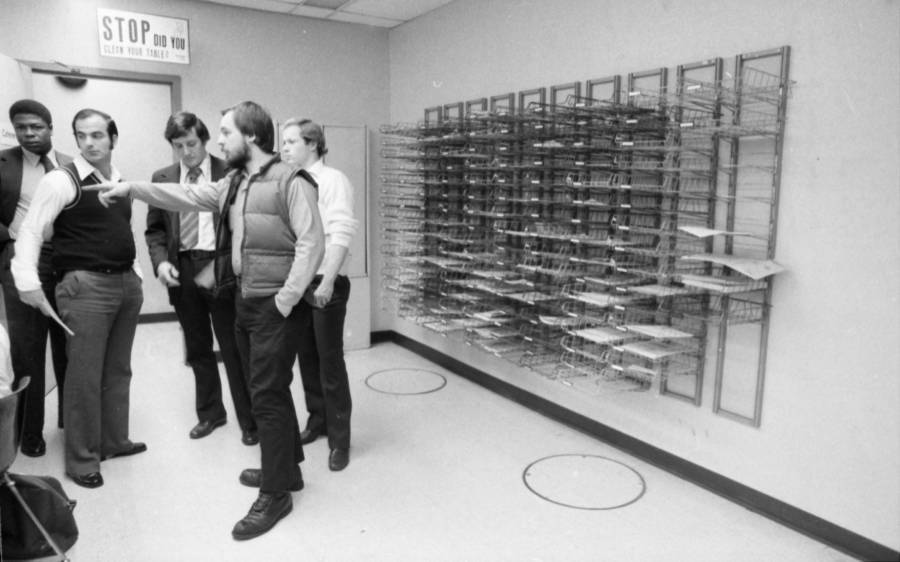

Nick Sorrentino/NY Daily News via Getty ImagesA Lufthansa employee showing police where he and his coworkers were tied up during the robbery. 1978.

In 1978, bookmaker Martin Krugman received a tip from an indebted friend.

Employees from the nearby JFK Airport knew that several airlines moved unmarked money by air during the day, which sometimes ended up in under-protected storage spaces at the airport.

By Krugman’s estimation, there should be a lot of money — untraceable and attainable money — at JFK.

At about 3 a.m. on Dec. 11, 1978, a group of armed gunmen raided the storage area of Lufthansa Airlines — and made off with more than $5 million in cash and almost $1 million in jewelry in a little more than an hour.

The Lufthansa Heist, as it came to be known, was the most “successful” robbery in American history up to that time. A little too successful.

The haul turned out to be way more money than the heist’s alleged mastermind, Lucchese crime family associate James Burke, had expected.

Burke was never officially inducted into the Lucchese crime family, despite being close with capo Paul Vario, because he was an Irishman, but as an outsider, he could partake without being directly linked to them in the underworld.

But when Burke realized just how much money the heist had sourced, he naturally began to worry about the inevitable investigation. Burke took to drastic defensive measures when police discovered the getaway van amateurishly dumped by the heist team.

By the summer of 1979, eight men associated with the heist — including Krugman and the getaway driver — were either murdered or missing. Much of this served as the real story behind Goodfellas, especially concerning the involvement of Lucchese associates Henry Hill and Tommy DeSimone.

While Burke was never formally charged with anything related to the heist, he was convicted on separate charges, including an unrelated murder. He later died in prison in 1996.

As for the money? Only a small portion was ever recovered by authorities.

While the remaining members and associates of the Lucchese family apparently figured out what to do with their haul, trouble was brewing within the Gambino family. And years of infighting would end poorly for Paul Castellano in the 1980s.

He had refused to grant Gambino members permission to trade in drugs, which angered the hot-blooded mobster John Gotti. Like Luciano before him, Gotti plotted a coup against the older generation in a bid for power.

Conspiring with fellow Gambino members, Gotti recognized that under Mafia law a hit against another Mafia boss required approval from the members of The Commission.

But this Commission’s members, who had known Castellano for years, would never agree to Gotti’s plot. So instead, Gotti reached out to more junior members and made alliances with them before proceeding.

Wikimedia CommonsSparks Steak House on 3rd Avenue and E. 46th Street as seen in 2008. In 1985, Gambino Family boss Paul Castellano was murdered here by men working for John Gotti.

Around Christmas time in 1985, Castellano was ambushed by gunmen at a Manhattan steakhouse while Gotti watched from a waiting car nearby.

Five hours after the shooting, two detectives showed up at Gotti’s home in Queens. “Paul got hit?” Gotti responded. “That’s too bad.”

Breaking with The Commission to kill a boss was not something to do lightly. In addition to insulting the basic principles of the Mafia’s hierarchical structures, there could be serious consequences for Gotti and the Mafia as a whole. And there were.

Looking Around And Looking Forward

Even if John Gotti had been able to hold his power together in the aftermath of his illegal betrayal of Castellano, he would have had to do so carefully.

He did not.

Wikimedia CommonsJohn Gotti as seen in his mugshot from 1990.

Gotti’s flamboyant behavior and dress — he famously bragged about his $1,800 suits — made him famous, the same way they had other bosses in the past. However, unlike Mock Duck in the early 1900s or Luciano in the 1930s, the attention Gotti earned in the 1980s and 1990s brought him down harder and faster than most.

After a string of court cases were the “Teflon Don” escaped conviction through jury tampering and witness intimidation, Gotti was finally taken down in 1992. After he was indicted for conspiracy to commit murder in the death of Paul Castellano, members of his own organization testified against him in court in exchange for reduced sentences on their end.

With his son, John A. Gotti “Junior,” left in charge of the Gambino family, Gotti spent the remaining years of his life in prison before dying of cancer in 2002 at age 61.

In the intervening years, following Gotti Junior’s several convictions in the late 1990s and early 2000s, he stepped down from leadership, leaving the position to the unfortunate Frank Cali.

While the influence of organized crime continues in New York, the United States, and around the world — as the assassination of Gambino family boss Frank Cali last March demonstrates — the exact future of the criminal underbelly remains uncertain.

The arrival of new gangs presents more rivals to the old families, and while new gangs can rise, it’s also possible for old ones to regroup and restructure. The biggest stumbling block could be just keeping these groups moving forward with recruitment.

Thanks to the heightened prevalence of snitching, increased penalties for Mafia crimes and improved opportunities for many youths in the traditional recruiting areas, there are fewer 30-year-olds willing to risk life in prison for the honor of being a “made man.”

The terms and associations no longer have the same currency they once held and do not attract the same level of candidates.

However, if one theory about the Cali killing proves true, it’s possible we are witnessing, not an aberration, but a return to form.

Frank Cali had roots in Sicily. Most of the current Gambino family is made up of Italian Americans. Whether this is another shift, like Luciano’s coup in the 1930s, or another step in a downward progression, only time will tell.

The only thing that is certain is that the end of organized crime in New York is still a long way off.

After this look at the history of some of New York’s most infamous gangs, meet some of the most notorious female gangsters. Then check out more of the most brutal gangs around the world.