A precursor to the modern American foster care system, the Orphan Train Movement was designed to give impoverished children in cities a better future. Instead, many ended up in the arms of poorly-vetted families seeking free labor.

Kansas State Historical SocietyAn orphan train in Kansas.

In the 19th century, the Orphan Train Movement started out as a humanitarian endeavor to pluck children out of the slums of East Coast cities and send them to good homes in the Midwest. There, they would learn to work, gain skills, and ultimately have a brighter future than they might have had in their home cities.

It was never supposed to be a child’s worst fear. But for many of the 200,000 children that stepped off the orphan train, onto foreign ground, and into strangers’ arms between 1854 and 1929, that’s exactly what it became.

Charles Loring Brace Arrives In New York With A Mission

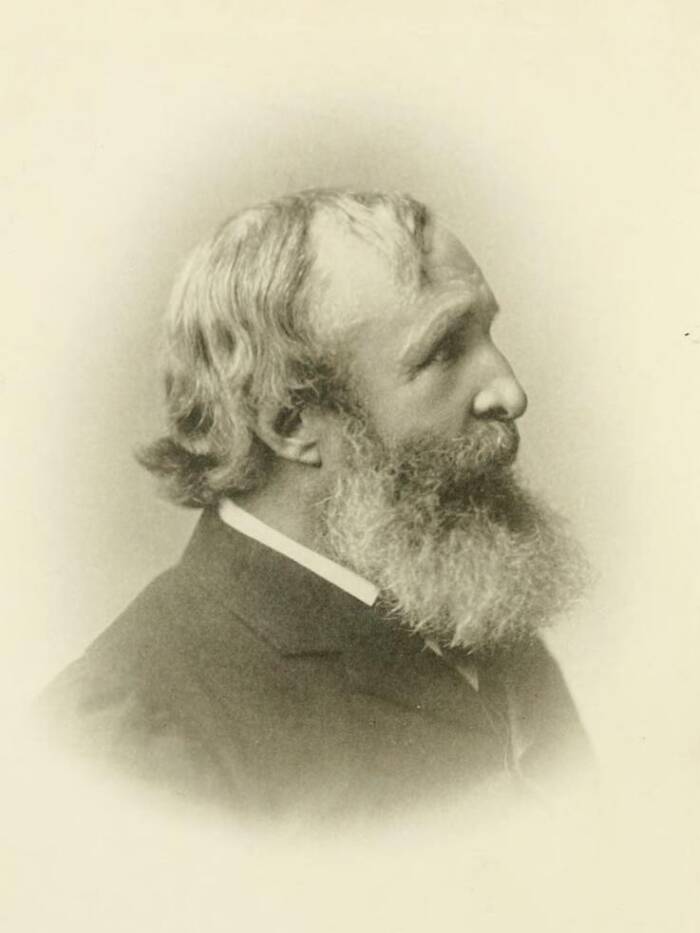

In 1849, the Orphan Train Movement’s founder, Charles Loring Brace, arrived in New York City. As a Presbyterian minister, Brace felt it was his duty to “evangelize the poor,” according to Humanities magazine. And, of course, there was no better place to find the poor than mid-1800s New York.

A densely populated hub for recent immigrants in the 19th century, the Five Points district of Manhattan had rapidly become America’s first slum. Over the years, the neighborhood had been ravaged by poverty, disease, and gang activity, leaving hundreds of people displaced. By 1850, between 10,000 to 30,000 children were living on the streets or in orphanages.

To combat this homelessness crisis, Brace founded the Children’s Aid Society in 1853. The organization began by offering young boys bible study classes, academic instruction, and organized meals. Eventually, the society also opened a shelter for boys known as the Newsboys’ Lodging House.

However, Brace had not accounted for the overwhelming number of boys in need of housing. Before long, the shelter was overrun — and Brace began looking for alternative options.

Public DomainCharles Loring Brace, founder of the Orphan Train Movement.

The Start Of The Orphan Train

As more and more children came to him looking for food and shelter, Brace began to believe that they might be better off outside of New York City — somewhere they could have access to more resources and education. As he searched the country for cities with families that were willing to house degenerate “street rats” and abandoned babies, he noticed that there was also a rising need for labor in the Midwest.

The center of the country was home to many farmers who were working tirelessly to maintain their ever-expanding farms. Brace believed that these farmers would jump at the chance to welcome the children into their homes, as it would mean more labor for them.

In the fall of 1854, the very first orphan train departed New York City for Dowagiac, Michigan, carrying 45 children. For four days, the children traveled in harsh, unsanitary conditions in cramped train cars, accompanied by only one adult: E.P. Smith from the Children’s Aid Society.

Along the way, Smith offered up two of the children to riverboat passengers without first checking the adults’ references. He also picked up another boy in Albany who claimed to be an orphan, but never verified this claim.

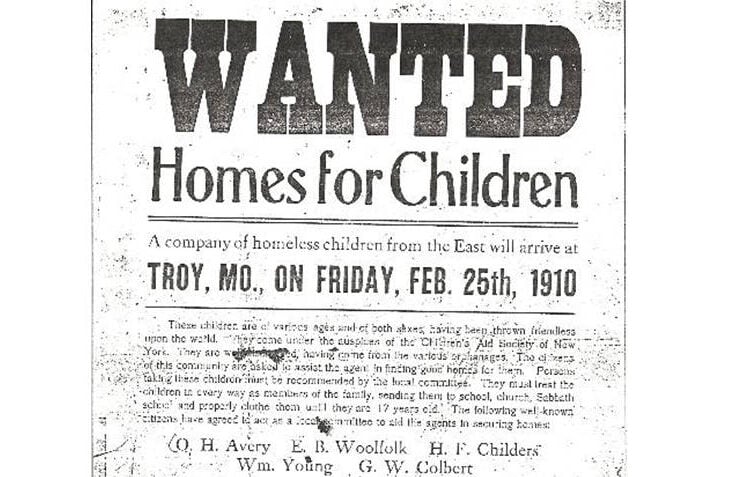

Wikimedia CommonsWanted poster advertising for families.

Once the children arrived in Michigan, local farmers and tradespeople gathered in the Dowagiac meetinghouse to get a look at them. According to Smith, those hoping to pick up a child had to have letters of recommendation from their pastor and a justice of the peace. However, there is no evidence that even this small requirement was enforced.

Out of the 45 children who arrived on the orphan train, only eight remained by the end of the week. Those eight were sent alone on a train to Iowa, where they were placed in a local orphanage.

Riding high on the “success” of the first orphan train, the Children’s Aid Society organized several more.

The Controversy Surrounding The Orphan Train Movement

Over the next 75 years, more than 200,000 children were transported from East Coast cities to towns not only across the American West and Midwest, but in Canada and Mexico as well. But while outside observers saw the trains as a wonderful solution to the rising homelessness problem in American cities, the reality for the children who rode them was often far more bleak.

The conditions on orphan trains were relatively grim. Overcrowded, cold, dirty, and with limited bathroom facilities, the trains wouldn’t stop for days at a time. The children often received only one meager meal a day.

Then, there were the children themselves. Though the trains were called “orphan trains,” many of their riders weren’t orphans at all. In fact, at least 25 percent of them still had two living parents. And in many cases, orphan train riders were not told where they were going before they were shipped off.

“I’d just finished eating and this matron came by and tapped us along the head. ‘You’re going to Texas. You’re going to Texas,'” an orphan train rider named Hazelle Latimer later recalled, according to VCU Libraries. “Well, some of the kids, you know, clapped and laughed. When she came to me, I looked up. I said, ‘I can’t go. I’m not an orphan. My mother’s still living. She’s in a hospital right here in New York.’ ‘You’re going to Texas.’ No use arguing.”

What’s more, many of the children who found themselves on the trains were separated from their siblings. If a family at the train’s destination only wanted one child, they rarely took into account whether that child had living relatives — sometimes sitting right next to them.

Today, few records exist as to what happened to these orphan train children after they were “adopted,” making it difficult for separated family members to find each other.

Public DomainChildren’s Aid Society group awaiting adoption.

The children also faced the prospect of ending up in a family that, rather than seeking a child to care for, was primarily interested in using them for free farm labor.

In fact, adoption events sometimes functioned much like auctions. After the orphan train children arrived in their new towns, they were typically paraded around at a public meeting place, where prospective adopters “came along and prodded them, and looked, and felt, and saw how many teeth they had.” Some potential foster parents would place specific orders for children based on their gender, age, size, and appearance.

“Some ordered boys, others girls, some preferred light babies, others dark, and the orders were filled out properly and every new parent was delighted,” a Nebraska newspaper reported in 1912, according to The Washington Post. “They were very healthy tots and as pretty as anyone ever laid eyes on.”

Paving The Way For The Modern Foster Care System

Public DomainChildren on the Orphan Train posing for the camera.

Eventually, in 1929, the onset of the Great Depression ended the Orphan Train program, as funding fell and families struggled to feed their own members, let alone take on more.

Leading up to its collapse, the Orphan Train Movement had also been facing an onslaught of public criticism. Abolitionist groups denounced the program as a glorified version of indentured servitude. And countless parents filed lawsuits against the organization, hoping to reclaim their children who’d been shipped away on orphan trains.

Even Brace himself questioned the ethics of his work.

“When a child of the streets stands before you in rags, with a tear-stained face, you cannot easily forget him,” Brace stated, according to PBS. “And yet, you are perplexed what to do. The human soul is difficult to interfere with. You hesitate how far you should go.”

As controversial as the Orphan Train Movement was, it did pave the way for its modern-day successor: the foster care system.

Inspired by the Brace’s idea to place downtrodden children into loving families rather than institutions, local agencies and state governments established a similar — though much more carefully vetted — system that is still in place nationwide today.

After reading about the orphan train, check out the story of Operation Babylift, when the U.S. evacuated more than 3,300 orphans from Vietnam. Then read about the hard work done by child laborers in the early 20th century.