Half-man and half-goat, the mysterious beast known as the Goatman is said to stalk forests and lurk beneath bridges waiting for the next victim in his murderous rampage.

Cryptid WikiMaryland and Texas each have their own tales of the Goatman — but the legends are very different.

At face value, the Goatman isn’t all that different from other cryptozoological urban legends. A mythical half-man, half-goat, the Goatman’s name has been used to instill fear in locals for decades.

And like many urban legends, the Goatman’s origins are muddy, with multiple variations of the tale, some involving dangerous scientific experiments, others claiming that he was a vengeful goat farmer.

Even the region in which his story originated is up for debate. While the Goatman has supposedly been seen in the woods of Maryland, folk in Alton, Texas seem to have as much claim to the story as their East Coast counterparts. Some argue that there are, in fact, two Goatmen, who share little more than a name.

In either case, the Goatman legend has become a pervasive staple of American mythology — and the legends are frightening enough to make even the most stubborn skeptic look over their shoulder if they find themself alone in the woods at night.

The Goatman Of Prince George’s County, Maryland

While Maryland’s Goatman was allegedly first spotted in 1957, when some people claimed to have seen a giant, hairy monster in Forestville and Upper Marlboro, the Washingtonian reports that one of the most popular legends involving the Goatman began on October 27, 1971 with an article in Maryland’s Prince George’s County News.

In the article, County News writer Karen Hosler mentions a few creatures from the University of Maryland Folklore Archives, including the Goatman and another figure, the Boaman, both of whom are said to haunt the wooded area surrounding Fletchertown Road.

Wikimedia CommonsFletchertown Road in Prince George’s County, Maryland, where the Goatman is said to jump onto cars and attack drivers.

The piece was a fairly in-depth exploration of the folklore of Maryland, without alleging that the Goatman or the Boaman were real.

But two weeks later, a local family’s puppy went missing. And a few days after that, they found the missing puppy near Fletchertown Road. It had been decapitated.

Hosler followed up with a new article, the headline reading, “Residents Fear Goatman Lives: Dog Found Decapitated in Old Bowie.”

Supposedly, her article claimed, a group of teenage girls heard strange noises on the night the puppy went missing — and other locals had reported seeing an “animal-like creature that walks on its hind legs” along Fletchertown Road.

On Nov. 30 that year, the Goatman was introduced to a national audience when The Washington Post published an article on the incident titled, “A Legendary Figure Haunts Remote Pr. George’s Woods.”

Is The Goatman Real?

Eventually, rumors about the Goatman’s origins started making the rounds. One popular story says that a doctor at the United States Department of Agricultural Research Center in Beltsville was conducting experiments, attempting to merge human and animal DNA.

The doctor allegedly tried to merge goat DNA with the DNA of his assistant, a man named William Lottsford, resulting in the creation of the Goatman — who has been on a murderous rampage ever since. Some say he was responsible for the 1962 murders of 14 hikers, whom he allegedly hacked to pieces while letting out unearthly screams.

Maryland folklore expert Mark Opsasnick first became interested in the Goatman legend as a child, having known of the legend growing up and gone on “Goatman hunts” with his friends.

In 1994, while working on a piece for Strange Magazine, Opsasnick managed to get in contact with April Edwards — the owner of the decapitated puppy.

“People came here and called it folklore, and the papers made us out to be ignorant hillbillies who didn’t know any better,” she told him. “But what I saw was real and I know I’m not crazy… Whatever it was, I believed it killed my dog.”

Wikimedia CommonsBowie, Maryland in the 1970s, where the legend of the Maryland Goatman is said to have originated.

April Edwards isn’t the only person to claim to have encountered the Goatman. Goatman sightings were a common feature of three distinct locations in Prince George’s County: a forest behind the St. Mark the Evangelist Middle School in Hyattsville, beneath the “Cry Baby” Bridge in Bowie, and in College Park.

In each instance, witnesses reported hearing devilish screams. Some claim that they have found bones, knives, saws, and leftover food in these locations.

Others claimed to have actually seen the Goatman near Governor Bridge, more commonly known as “Cry Baby” Bridge. The story goes that if you park beneath the bridge once the sun has set, you can hear the sounds of a baby crying, or possibly a braying goat.

Then, suddenly, the Goatman will be upon you, leaping onto your car, attempting to get inside and attack you or rip you out of your seat. It is said that he targets couples more often, and some people say that he kills pets and breaks into houses, dragging his victims back into the forest.

George BeinhartThe old Governor’s Bridge, otherwise known as “Cry Baby Bridge” in Maryland.

Still, Opsasnick told the Washingtonian that while he believes the locals he’s talked to about Goatman really did see something, he doesn’t believe Goatman exists.

“I can’t believe in something until I see it with my own eyes,” he said. “Anything is possible in this world… Maybe there is a half-man, half-animal creature out there.”

For its part, the United States Department of Agricultural Research Center has shot down the rumors that Goatman originated there. “We just think it’s stupid,” spokesperson Kim Kaplan told Modern Farmer in 2013.

“Don’t you think he would have retired by now?” she added. “Is his great-grandson a Goatman? Is he collecting Social Security?”

But Maryland is not the only state where locals speak of the Goatman. The other Goatman lives further south, in the town of Alton, Texas — and his story is one of racist intolerance that has haunted the area for almost a century.

The Legend Of Old Alton Bridge In Texas

In the mid-19th century, Alton, Texas was a small town that served as the seat of Denton County. It sat on a high ridge between Pecan Creek and Hickory Creek, but despite being the county seat, no public buildings were ever built.

In fact, according to Legends of America, the only residence in the area belonged to W.C. Baines, whose farm had existed since long before Alton’s new designation. As a result, Baines hosted many public discussions in his yard until November of 1850 when it was decided that the county seat would move to a new location.

This new location kept the name Alton, and within a few years was populated by a small citizenship, a blacksmith, three stores, a school, a saloon, a hotel, two doctors, and a few lawyers. In 1855, the town welcomed the Hickory Creek Baptist Church, which remains there to this day.

Wikimedia CommonsThe Old Alton Bridge, constructed in 1884 by the Ohio-based King Iron Bridge & Manufacturing Company, also known now as “Goatman’s Bridge.”

Unfortunately, Alton didn’t remain the county seat for long, and by 1859, most of its residents had packed their bags and moved to the new seat, Denton.

If it weren’t for the construction of the Old Alton Bridge in 1884, the town would have likely been nothing more than a footnote in history. However, most people now know the Old Alton Bridge by another name: Goatman’s Bridge.

This Goatman, however, did not live his life as a half-man, half-goat mutant. He was, according to local legend, a perfectly normal Black man named Oscar Washburn who happened to make a living raising goats.

Washburn was actually a fairly successful businessman, and had become so popular among the locals that they started referring to him affectionately as “the Goatman.” Washburn too, it seemed, took a liking to the monicker.

One day, Washburn put up a sign near the Old Alton Bridge that read, “This way to the Goatman.” Unfortunately, this drew the ire of local Ku Klux Klan members who hated to see a Black man be successful.

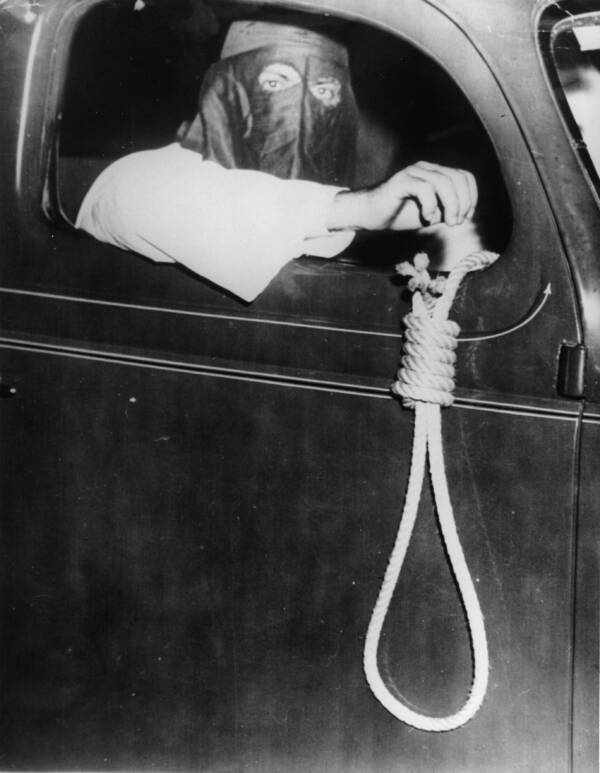

In August 1938, KKK members got in a car, drove it to the Old Alton Bridge, and turned off their headlights.

From there, they walked to Washburn’s home and dragged the Goatman to the bridge where they tied a noose around his neck and threw him over the edge.

Imagno/Getty ImagesA member of the Ku Klux Klan holding a noose out of a car window in 1939.

The legend goes that when they peered over the edge to see if Washburn was dead, they saw nothing but rope. Washburn’s body was never seen again. The KKK weren’t done, though — they returned to Washburn’s home and slaughtered his family.

Now, if the tales are to be believed, it is said that anyone who drives across the Goatman’s bridge at night with their headlights off will find him waiting on the other side.

Some say they see only a ghostly figure of a man herding some goats. Others say the Goatman stares them down, a goat head under each of his arms.

People have also reported seeing a half-goat, half-man figure, hearing the sound of hooves on the bridge or inhuman screams and laughter coming from the forest and creek below, or seeing a pair of glowing eyes at the end of the bridge.

It’s hard to say how much of the Texas Goatman’s legend was true — historical records don’t show that an Oscar Washburn ever lived in the area. But the story has certainly been powerful enough to draw people to the Old Alton Bridge to find out for themselves.

After learning about the legends of the Goatman, explore some more North American folklore by reading about the Jersey Devil, the horse-headed monster said to reside in the Pine Barrens, or the Bunny Man of northern Virginia.