According to Greek myth, three monstrous sisters named Medusa, Stheno, and Euryale lived "beyond glorious Ocean in the frontier land towards Night" — and they could turn men to stone with a single look.

Wikimedia CommonsA depiction of three Gorgons outside of Secession Hall in Vienna, Austria.

Somewhere between man, beast, and divine existed a band of sisters in ancient Greek mythology. Boasting venomous snakes for hair and the ability to turn men to stone, the Gorgons were powerful female monsters.

Stheno, Euryale, and the most famous of the trio, Medusa, are familiar motifs in Greek literature and artwork. Even thousands of years later, artists, writers, and brands invoke the ancient magic of Gorgons and their petrifying powers.

But the legacy of these sisters is much more fascinating than simple villains in a hero’s quest — for those daring enough to look them in the face.

Who Were The Gorgons?

Public DomainA 16th-century depiction of Medusa, the most famous Gorgon, by the Italian painter Caravaggio.

Their appearance has shifted through the millennia, but two aspects of the Gorgons remain largely steadfast: their arresting hair and petrifying powers.

Greek writer Pseudo-Apollodorus described the sisters as creatures who possessed “heads with scaly serpents coiled around them, and large tusks like those of swine, and hands of bronze, and wings of gold which gave them the power of flight; and they turned all who beheld them to stone.”

Playwright Aeschylus evoked “three winged sisters, loathed enemies of humankind, the snake-haired Gorgons, whom no man can see and live.”

Their commonality was their monstrousness, expressed through their serpent-locks, and their ability to turn careless onlookers into stone.

Palazzo Massimo alle Terme/Wikimedia CommonsThe Gorgon sisters boasted terrifying powers, but Medusa had a notable weakness: her mortality.

Despite these horrifying features, Gorgons would prove a lasting motif in Greek culture, eventually becoming a protective token in some communities. Later on, they would come to symbolize female rage. But for many ancient Greeks, they seemed to be straight out of a bone-chilling nightmare.

Their depictions throughout the years have reflected a wide variety of cultural outlooks, both in the ancient world and the modern world. But the three sisters have always represented otherness, or a sort of female wildness, in comparison to those in more civilized societies.

The Origins Of The Snake-Haired Monsters

The origins of the Gorgons vary like their depictions, but according to most Greek myths, the snake-haired monsters were the children of the sea god Phorcys and his sister-wife Ceto. The petrifying mythical creatures were said to dwell “beyond glorious Ocean in the frontier land towards Night.”

The Gorgons’ names likely reflect their most prominent traits, with Stheno’s name meaning “the mighty” or “the strong,” Euryale’s name meaning “the far springer,” and Medusa’s name meaning “the guardian” or “the queen.”

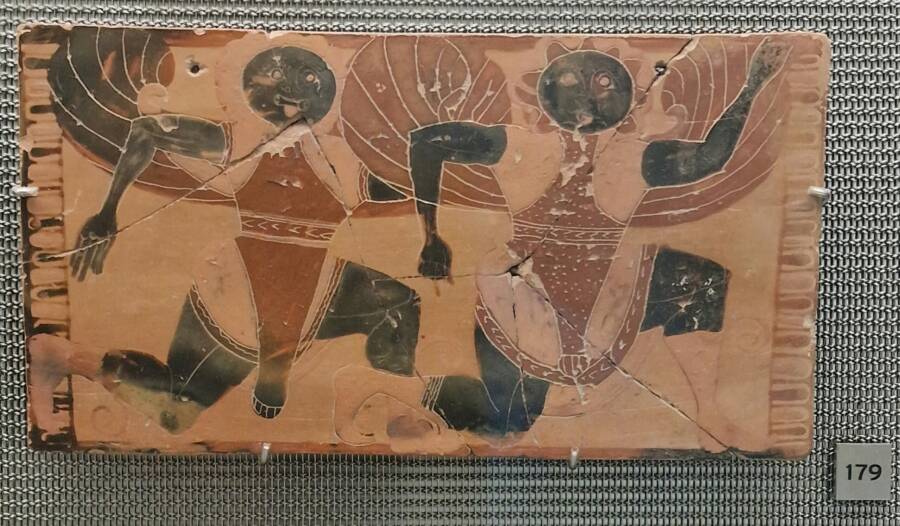

Acropolis Museum/Wikimedia CommonsA depiction of the Gorgons on a plaque.

Their parentage meant that they possessed divine traits. All of the sisters were immortal, except for the most famous sister, the one whose name would rule over all Gorgon stories for the rest of time: Medusa.

Though Medusa was usually safe from enemies thanks to her dangerous gaze, she became incredibly vulnerable when she was asleep.

Medusa, The Most Notorious Gorgon

By far the most famous Gorgon, Medusa is the one most familiar to a modern audience. In the ancient world, she was also quite famous, but the versions of her myth have evolved with the mores and values of the time.

While some early versions of her myth seem to imply that she was a monster from birth, one of the most famous tales about Medusa portrays her as a doomed character who was once a beautiful human woman.

Her stunning features, including “golden ringlets” of hair, caught the attention of Poseidon (the god of the sea, earthquakes, and horses), who had his way with her at Athena’s temple. Some versions of the story describe the act as consensual, while others depict it as rape. In either case, Athena considered this a desecration of her sacred shrine and she set out to punish Medusa.

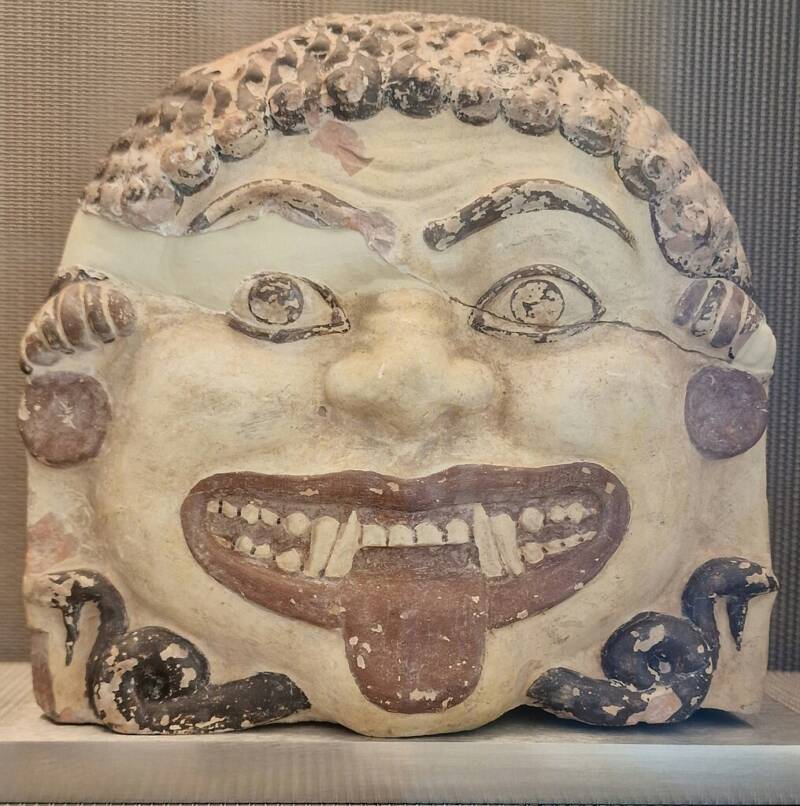

Acropolis Museum/Wikimedia CommonsA frightening depiction of a Gorgon.

That’s why the goddess of wisdom supposedly transformed Medusa’s gorgeous hair into “hissing snakes.” Her once lovely face was cursed to stun all onlookers to stone, meaning she’d petrify any future suitor.

Medusa and her sisters then retreated from the world of men, until a Greek hero disturbed their seclusion with bloodlust in his heart.

Perseus And Medusa: A Blood-Soaked Encounter

Like Medusa, Perseus had some divine origins.

The child of Danaë, the princess of Argos, Perseus was sired after Zeus, the god of the sky, had sex with Danaë in the form of a shower of gold. Danaë and Perseus were soon cast out into the sea by Perseus’ own grandfather Acrisius, who feared a prophecy that Danaë’s child would be his killer.

The mother and son were eventually rescued by a fisherman named Dictys, who helped bring up Perseus on the island of Seriphus. Meanwhile, the lecherous King Polydectes of Seriphus began relentlessly pursuing Danaë.

To protect his mother from marrying Polydectes, Perseus swore to retrieve the head of Medusa in exchange. Knowing the Gorgon’s fierce reputation, Polydectes figured he would neatly gain Danaë’s hand in marriage and be rid of an unwanted stepson in the process. But Polydectes was wrong.

Wikimedia CommonsA statue of Perseus slaying Medusa.

Aided by Athena and Hermes, Perseus was armed with winged sandals, Hades’ cap of invisibility, a sickle, a magical knapsack, and a bronze shield.

Arriving at the Gorgons’ lair, the hero used the shield to avoid Medusa’s gaze in case she unexpectedly woke up. The hero crept up on the sleeping Gorgon, carrying his godly tools so he would not be petrified, and successfully beheaded her by using the sickle.

From Medusa’s neck spurted the winged horse Pegasus and Chrysaor (either a humanoid warrior or a boar), which had been fathered by Poseidon.

Perseus stuffed Medusa’s head in his magical knapsack, a key part of his mission complete. But his journey was far from over.

Stheno And Euryale: The Other Gorgon Sisters

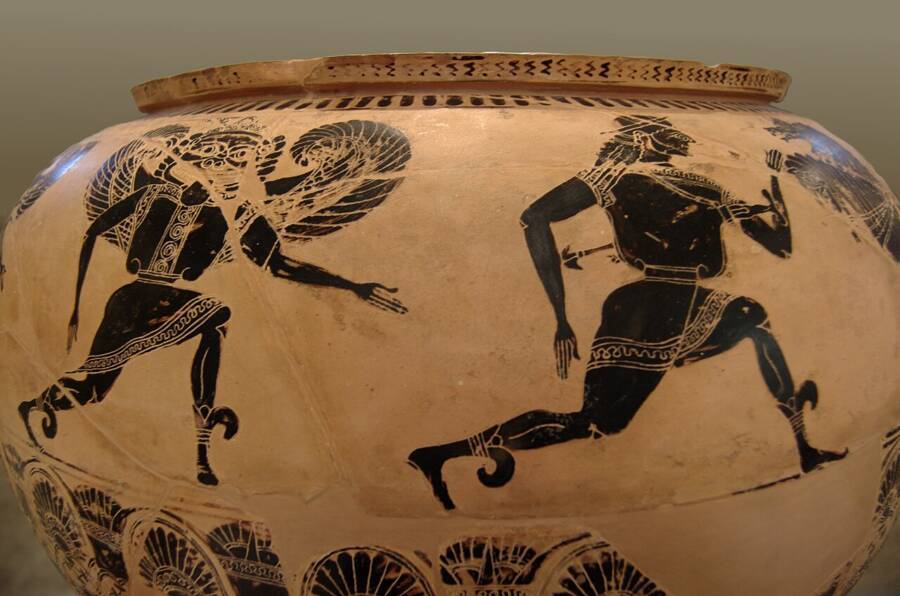

Stheno and Euryale, the “undying” Gorgons, quickly realized their sister had been murdered after they woke up and began chasing after her killer.

Since Stheno and Euryale were both immortal, there was no way for Perseus to kill them too, so he was forced to flee their wrath.

Concentrating their fury and gnashing their frightening jaws, the Gorgons tried to attack Perseus, but to no avail. Hades’ cap rendered him invisible, and thanks to the winged sandals, he was out of the lair in no time.

Public DomainAn illustration of Perseus running away from one of Medusa’s Gorgon sisters.

The sisters let out a terrible wail of sorrow. According to the Greek poet Pindar, their cry was so powerful and so piercing that Athena invented the aulos, a musical wind instrument, to mimic the noise.

The Legacy Of The Gorgons In Legend — And In The Modern World

Symbolically and literally (according to the myths, anyway), Medusa’s powers lived on. Perseus used Medusa’s severed head to defeat Polydectes, his malevolent would-be stepfather, saving his mother Danaë.

Polydectes wasn’t the only enemy Perseus took down with Medusa’s head. Legend has it that he used it to turn the Titan Atlas into the Atlas Mountains in Northern Africa after Atlas denied Perseus a place to rest.

Wikimedia CommonsA Gorgon symbol, reportedly taken from the breastplate of Philip II of Macedon’s tomb in Vergina, Greece.

The use of Medusa’s head didn’t end with Perseus. In some tales, Athena used the head on her shield to intimidate her enemies. In other stories, the head is used by Hades to keep the living away from the world of the dead.

In the real world, some ancient Greeks used the Gorgon’s head as a symbol of fear, but the head also became a sign of protection.

Medusa’s head has been found on a number of incredible artifacts, such as a plaster mold used to make Medusa masks 2,000 years ago in Sicily, a mosaic of the Gorgon inside a Roman-era home in Spain, and a 1,800-year-old Roman medal emblazoned with the face of the monster in England.

Even today, some decorate their homes and personal items with images of Medusa and her Gorgon sisters, especially those fascinated by ancient beliefs that she could protect buildings and turn away malevolent forces.

Most famously, Medusa’s head graces the luxury clothing, purses, and other items from the brand Versace. The brand’s founder Gianni Versace purportedly chose the logo after recalling that he saw it in ancient ruins that he and his siblings played in when they were children. In his interpretation, the Gorgon compelled onlookers to fall in love with her and never recover.

In other modern interpretations, Medusa is given a more sympathetic portrayal, especially in stories and artworks where she’s depicted as a victim of Poseidon’s sexual violence. She and her Gorgon sisters have gained some significance among some feminists as well, as a symbol of female rage and sisterhood, and for their status as “others” positioned outside of society.

For millennia, the story of the Gorgons has said a lot about society and how values and customs have changed depending on the time and place. Long after they first appeared in myths, the sisters are still mired into the cultural zeitgeist as permanently as if they were etched into stone.

Next, go inside the Greek myth of Arachne, the talented weaver who was turned into a spider by Athena. Then, discover the legend of the Minotaur, the bull-headed monster of the Greek Labyrinth.