Medusa is the most infamous of all the Gorgons in Greek legend. But is she really a formidable monster or a tragic victim?

Peter Horree/Alamy Stock PhotoMedusa, as depicted on a Roman chariot pole ornament from the first to second century C.E.

As the story goes — passed down from generation to generation, embellished by Greek and then Roman writers — Medusa was a fearsome monster who was eventually slain by Perseus. Medusa’s hair, made of writhing snakes, and her ability to turn men into stone made her a formidable foe. But Perseus prevailed thanks to deities like Athena, and he was able to use Medusa’s decapitated head for his own purposes.

In this tale from Greek mythology, Perseus is the hero. But who was Medusa?

The legend of Medusa is about much more than a hero triumphing over a villain. It’s about sex, violence, revenge, and power. And in modern times, Medusa’s story has been given a second look, where she is sometimes seen more as a tragic, misunderstood victim than a fearsome monster.

Medusa: One Of The Gorgon Sisters

One of the earliest mentions of Medusa comes from Hesiod’s Theogony, a poem about the Greek gods written between 730 and 700 B.C.E. Medusa is mentioned just once, but Hesiod provides the initial framework for her story.

Hesiod writes that Medusa and her sisters, Stheno and Euryale, are the Gorgons — the daughters of sea god Phorcys and his sister-wife Ceto — who dwell “beyond glorious Ocean in the frontier land towards Night.” In ancient Greek, the word “gorgon” can mean “grim,” “fierce,” and “terrible.” The Greek poet Homer also mentioned the Gorgon in the Odyssey (written around 750 to 650 B.C.E.), but as a singular monster: “the monster’s head, the Gorgon.”

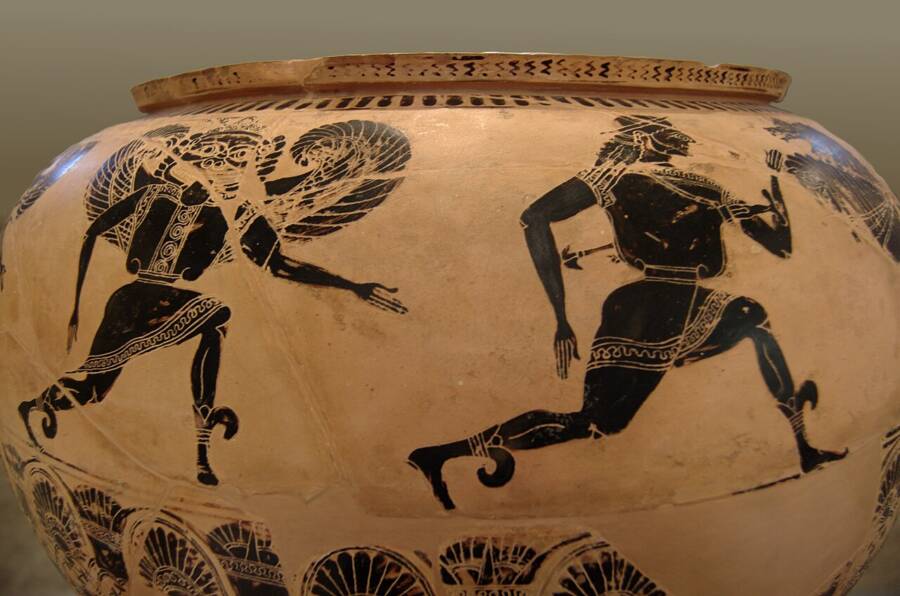

Public DomainA depiction of Perseus fleeing from one of Medusa’s Gorgon sisters. Circa 600 to 580 B.C.E.

Though the sisters are all Gorgons, Medusa is different from the others: She’s mortal, while Sthenno and Euryale are immortal and “undying.” Hesiod also remarks that Medusa suffers “a woeful fate.”

Hesiod offers just a few other details about Medusa’s life. By writing that Medusa “lay [with] the Dark-haired One in a soft meadow amid spring flowers,” Hesiod establishes that Medusa slept with Poseidon, the god of the sea, earthquakes, and horses (also called Neptune in Roman mythology). Hesiod also adds that “Perseus cut off her head” and that Chrysaor and Pegasus (Medusa’s sons fathered by Poseidon) “sprang forth” from her body.

Thus, Hesiod established Medusa’s connection to more prominent figures in Greek mythology like Poseidon, Perseus, and Pegasus. He and Homer also suggest that she is a monster, an interpretation accepted and built upon in later works like Aeschylus’ Greek tragedy Prometheus Bound (which was written sometime between 479 B.C.E. and 424 B.C.E.).

Though Aeschylus did not directly mention Medusa, he offered both a physical description of the Gorgons and hinted at their powers when he wrote: “The sisters three, the Gorgons, have their haunt; Winged forms, with snaky locks, hateful to man, Whom nothing mortal looking on can live.”

Wikimedia CommonsA Gorgon depicted on the Temple of Artemis in Corfu, Greece, first created circa 580 B.C.E.

Other writers, however, would add to the Medusa legend over the next several centuries. They further explained what she looked like, her encounter with Poseidon, and how she was punished by Athena.

How Medusa Was “Cursed” By Athena

Writers like Hesiod established Medusa as a monster, one of the fearsome Gorgon sisters. But later writers would tweak the legend to claim that she had once been a human woman who was later cursed by the gods.

Jebulon/Wikimedia CommonsThe Temple of Athena Nike in Athens, Greece. Some legends state that Medusa was raped in a temple to Athena by Poseidon, and then was cursed for desecrating a holy place.

In Metamorphoses, which was written around 8 C.E., Roman poet Ovid describes Medusa as a beautiful human woman with a sweet face and “golden ringlets.” She draws the attention of many suitors (a “rival crowd of envious lovers”), including the god Neptune, or Poseidon.

Though Hesiod merely wrote that Medusa “lay” with Poseidon, Ovid describes their encounter differently. Neptune, he writes, “resolv’d to compass, what his soul desir’d” and “seiz’d” the “young, blushing maid.” The fearsome god of the sea then rapes Medusa in a temple to Minerva (Athena).

(There are also versions of the myth that claim Medusa had pledged celibacy to Athena and that her encounter with Poseidon at Athena’s temple — sometimes depicted as a consensual one — broke this vow.)

Minerva, furious at this desecration of her temple, decides to curse Medusa.

Ovid writes:

“But on the ravish’d virgin vengeance takes,

Her shining hair is chang’d to hissing snakes.

These in her Aegis Pallas joys to bear,

The hissing snakes her foes more sure ensnare,

Than they did lovers once, when shining hair.”

In other words, Minerva punished Medusa by turning her “golden ringlets” into “hissing snakes.” Other versions of the legend additionally claim that Minerva also made it so that if a man looked upon Medusa, he would turn into stone — thus condemning her to spend her life alone.

Ovid and other writers thus offered a new variation of the Medusa story. Instead of establishing her as a monster from birth, they suggested that she’d been a maiden cursed to be a monster by a deity.

Carole Raddato/Wikimedia CommonsA Medusa mosaic in Rome, dating from the first or second century C.E.

But Medusa is perhaps best known for the role she plays in another legend. In the story of Perseus, she is a monster slain by a hero.

The Legend Of Perseus

Perseus’ legend starts with his mother, Danaë. When an oracle told her father Acrisius, the King of Argos, that Danaë’s son would kill him, the king had Danaë locked up in a prison. But the god Zeus was able to impregnate Danaë there, and she later gave birth to their child: Perseus.

Public DomainA first-century C.E. mosaic of Perseus and his wife, Andromeda.

Terrified of the child, Acrisius sent Danaë and Perseus out to sea in a wooden chest. They were rescued by Dictys, a fisherman who later helped raise Perseus, on the island of Seriphus. But King Polydectes of Seriphus eventually wanted Perseus out of the way so that he could marry Danaë.

So, Polydectes sent Perseus on what seemed like an impossible quest: to slay Medusa the Gorgon and bring back her head of writhing snakes. The king assumed that Perseus would be killed by the monster. But he didn’t realize that Perseus, the son of Zeus, would have help from above.

Legends state that Hermes and Athena helped Perseus attain winged sandals, a sickle, a bronze shield, the invisibility cap of Hades, and a magical knapsack to carry the head. In some tellings, Athena participated in the quest because Medusa had allowed her beauty to be compared to Athena’s.

Hermes and Athena also helped guide Perseus to Medusa’s lair, where she lay sleeping with her Gorgon sisters. Staring into the reflection of his bronze shield — to avoid being turned to stone in case Medusa woke up — Perseus successfully cut off Medusa’s head with his sickle.

Wikimedia CommonsA statue of Perseus with the head of Medusa.

After the decapitation, Chrysaor and Pegasus, Medusa’s two sons fathered by Poseidon, suddenly “sprang forth” from her neck. Perseus then fled with Medusa’s severed head as her sisters chased after him. With the help of the winged sandals and the invisibility cap, Perseus escaped easily.

But even though Medusa was dead, her head remained a potent weapon.

The Power Of Medusa’s Head

As Perseus made his way back to Seriphus, he carried Medusa’s head in a magical knapsack called a kibisis. He soon realized that the head still had the ability to turn men to stone — which he’d use to his advantage.

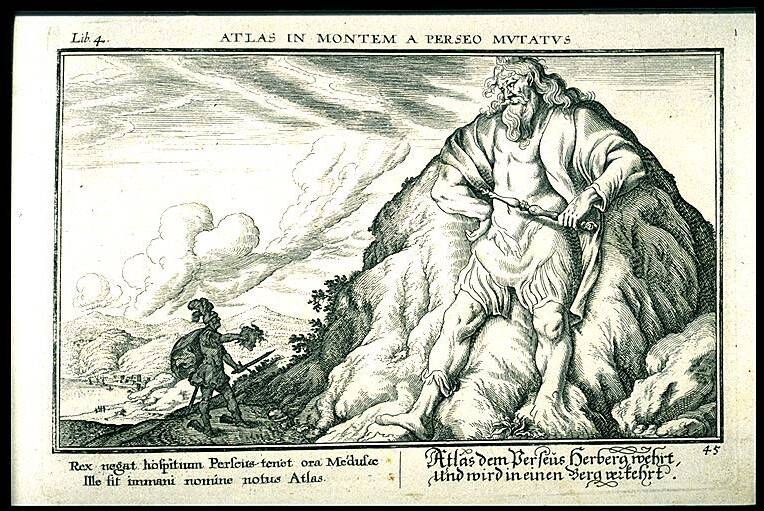

When Perseus encountered the Titan Atlas, for example, he asked for a place to rest during his journey. But Atlas, who had heard a prophecy about someone stealing his sacred golden apples, refused. Perseus knew he couldn’t defeat the Titan in battle, so he used Medusa’s head as a weapon — and purportedly turned Atlas into the Atlas Mountains in Northern Africa.

Public DomainA 17th-century depiction of how Perseus used Medusa’s head to defeat Atlas.

Perseus also came across a woman named Andromeda, who had been tied to a rock as an offering to a sea monster. Her mother had offended sea nymphs called the Nereids by saying that she was more beautiful than they were, and Andromeda was thus offered as a sacrifice to stop the sea monster from wreaking havoc. But Perseus swiftly fell in love with Andromeda, and — in some tellings of the myth — used Medusa’s head to defeat the sea monster and rescue Andromeda from certain death.

Then, back in Seriphus, he used the Gorgon’s head to defeat Polydectes and his supporters, so that he could rescue his mother Danaë.

Perseus then installed Dictys as king, and gave Medusa’s head to Athena, who placed it on her shield to intimidate her foes during battle.

Sergey Sosnovskiy/Wikimedia CommonsThis mosaic from the first century C.E. depicts Athena with her shield.

It’s little wonder why the story of Medusa captivated so many people in ancient Greece — and it still captivates people today.

From Mosaics In Ancient Greece To #MeToo

In ancient times, Medusa frequently appeared in mosaics, pottery, and art. Her likeness was also often used on shields, breastplates, and protective amulets since the head of the Gorgon — called Gorgoneion — was thought to have protective properties. (Indeed, Medusa’s name comes from an ancient Greek verb that roughly means “to guard” or “to protect.”)

Medusa remained a subject of fascination for artists throughout the ages, and she — and her beheading by Perseus — has been depicted by countless artists ranging from Leonardo da Vinci to Salvador Dalí.

Public DomainA 16th-century depiction of Medusa by Italian painter Caravaggio.

The infamous Gorgon continues to draw interest in modern times. In the 1981 film Clash of the Titans, Medusa is depicted as a terrifying monster who lives in the Underworld. She’s guarded by a two-headed dog similar to Cerberus. And just like in the classic myth, she’s defeated by Perseus.

(In the film, however, Perseus’ motives are slightly different — he kills Medusa because he needs her head to defeat the Kraken.)

That said, Medusa is given a more sympathetic portrayal in some modern tellings of the legend. Though Rick Riordan’s Percy Jackson and the Olympians book series depicts Medusa as a monster, the TV show offers a more nuanced look at her origin story and motivations.

In the TV show, Medusa expresses anger toward Athena and Poseidon. Without going into explicit details — which could be inappropriate for a show geared toward children — Medusa hints at what happened by describing her admiration for Athena, her relationship with Poseidon, and how Athena unfairly punished her, and not Poseidon, for the disgrace they caused.

Indeed, Medusa even became a symbol of the #MeToo movement after women started to publicly share their stories of sexual abuse and harassment in 2017. A few years into the movement, a statue of Medusa holding Perseus’ head was installed across the street from a criminal courthouse in Manhattan. There, a number of men who’d been accused of sexual assault during the #MeToo movement were prosecuted.

Luciano Garbati This 2008 statue of Medusa holding the head of Perseus (by Luciano Garbati) later became a #MeToo symbol.

However, some critiqued the sculpture because it was created by a man and because Medusa held the head of Perseus and not her rapist, Poseidon.

But the statue — and the Percy Jackson and the Olympians TV series — shows an interesting evolution in our understanding of Medusa. Long seen as a monster cursed by the gods, modern-day interpretations have presented her more as a misunderstood victim.

This adds a new complexity to the myth of Medusa, the monster with snakes for hair who can turn her victims to stone.

After reading about the story of Medusa, learn the astonishing stories behind some of the most terrifying mythological gods. Or, discover the dark and disturbing truth behind the legend of Hades and Persephone.