London's Great Stink of 1858 didn't merely cause nausea citywide, it led to world-changing developments in science and engineering.

Punch Magazine/Wikimedia CommonsThe silent highwayman: Death rows on the Thames, claiming the lives of victims who have not paid to have the river cleaned up, during the Great Stink. [Cartoon from Punch Magazine. July 10, 1858.]

In 1858, a powerful stench terrorized London for two months.

The source of what’s now known as the Great Stink was the River Thames, into which the city’s sewers emptied. Between 1800 and 1850, the amount of waste that these sewers dumped into the river greatly increased as the city’s population more than doubled, while the installation of flushable toilets in the city further increased the amount of waste that the river received.

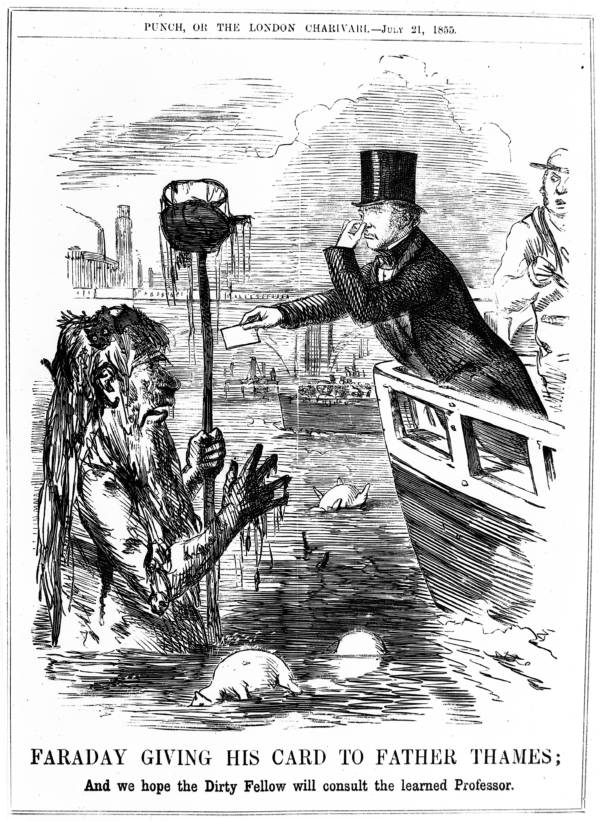

In 1855, scientist Michael Faraday reported that the waste from the sewers had turned the river’s water into “an opaque pale brown fluid” with an unpleasant smell and dense clouds of fecal matter.

Punch Magazine/Wellcome ImagesA cartoon showing Michael Faraday meeting the dirty spirit of the River Thames.

Then, in the summer of 1858, a heat wave hit the city and caused the extraordinary amount of waste within the river to ferment, which made the river smell worse than it ever had before.

British newspapers referred to the river’s stench as the Great Stink, with one article stating, “Gentility of speech is at an end–it stinks, and whoso once inhales the stink can never forget it and can count himself lucky if he lives to remember it.”

As this statement implies, people believed that the stench was not only unpleasant but also deadly, because bad smells were widely thought to spread diseases, including cholera.

Between 1831 and 1854, three cholera epidemics hit the city, each killing thousands of Londoners. Now, people across the city believed that they could get cholera once more from the Great Stink.

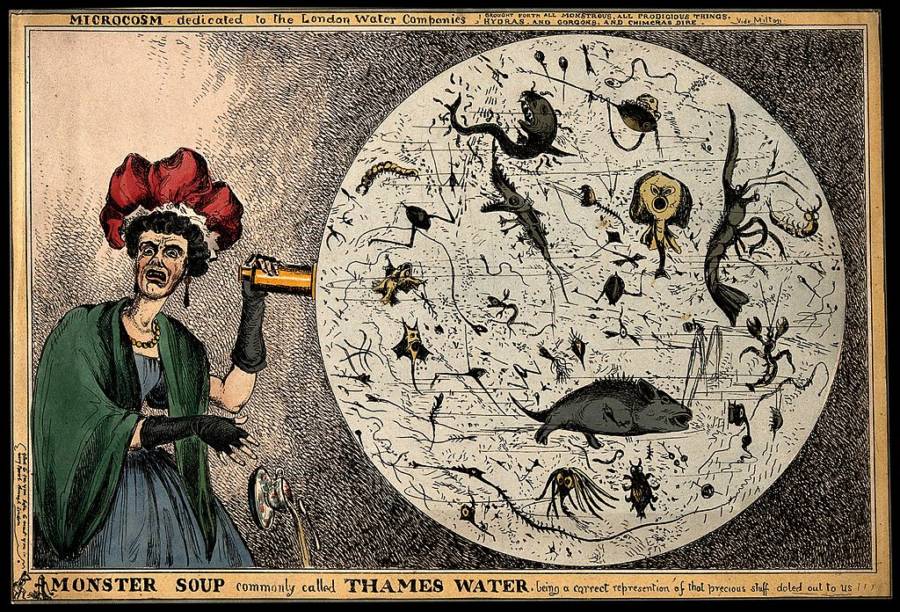

William Heath/Wellcome Images/Wikimedia Commons“Monster Soup commonly called Thames Water.” An illustration depicting the creatures believed to be lurking in the polluted water of the Thames.

However, a physician named John Snow determined that Londoners’ fear of the Great Stink was misplaced.

During the third cholera epidemic that struck the city, Snow investigated the disease’s spread in the neighborhood of Soho. He had correctly suspected that the disease spread through contaminated water, rather than bad smells. To prove his theory, he removed the handle from the neighborhood’s water pump.

Snow’s removal of the handle prevented the neighborhood’s residents from drinking the water that he suspected was contaminated and giving them cholera. Following his removal of the handle, the neighborhood exhibited a fall in deaths due to cholera.

The fall in deaths seemed to validate Snow’s theory. It also suggested that Londoners needed to worry less about bad smells and more about the quality of their drinking water, much of which came from the river and was thus badly contaminated.

However, little consideration was given to Snow’s investigation into cholera’s cause. Londoners thus kept being afraid of the supposedly deadly nature of the river’s stench.

Following the Great Stink’s increase in severity, Parliament decided to pass a bill to create a new sewer system for the city. This decision was partly a response to Londoners’ fear of the Great Stink and partly a response to the stench making it unpleasant for members of the Parliament, which is housed right on the north bank of the river, to show up for work.

The bill enabled a brilliant engineer named Joseph Bazalgette to construct 82 miles of new sewers. The new sewers moved London’s waste eastward beyond the city, where it could flow more easily into the ocean. Consequently, the Great Stink went away and both the river and Londoners’ drinking water became cleaner.

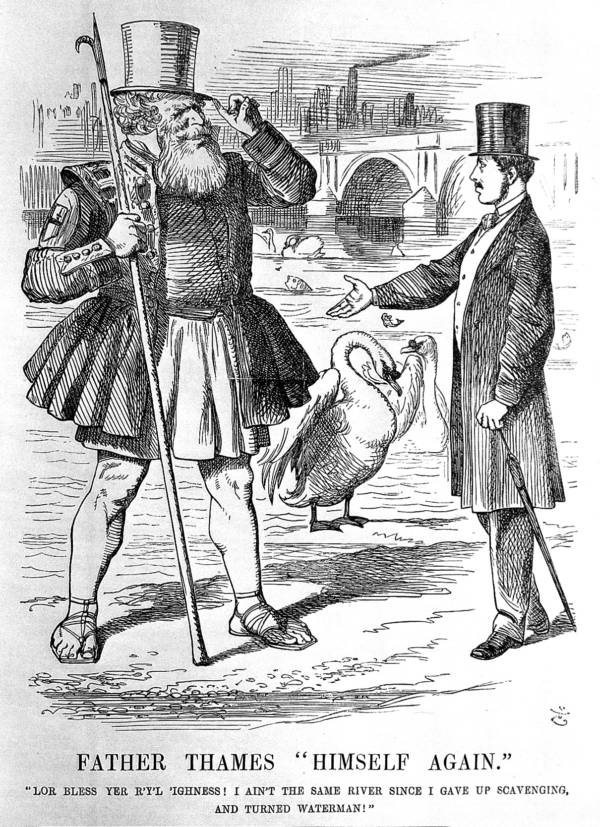

Punch Magazine/Wellcome ImagesA cartoon showing the spirit of the river, happy and clean as a result of the construction of Bazalgette’s sewer system.

Only one more cholera epidemic hit London, in 1866. This epidemic was confined to an area of the East End of London, which was the only part of the city that had not yet been connected to Bazalgette’s sewer system, which made people realize that Snow had been right about the disease being waterborne.

The actions that Londoners took to end the Great Stink and make their city smell better thus ended up saving lives and helped discredit a false theory about how diseases spread. These measures also paved the way for further efforts to depollute the River Thames, which, amazingly, is now currently considered to be one of the world’s cleanest rivers.

After this look at London’s Great Stink, check out the 143-ton ball of feces, fat, and condoms recently found to have been clogging London’s sewer system. Then, see shocking images of pollution in present-day China.