The prolonged campaign of Guadalcanal saw repeated, ferocious attempts by the Japanese to retake the island and its strategic airfield from the United States.

Although not as well-known as the Battles of Midway or Iwo Jima, the Battle of Guadalcanal played a key role in the Pacific Theater of World War II. The six-month-long Guadalcanal Campaign took place on and around the island of Guadalcanal, one of the Solomon Islands located in the South Pacific, to the northeast of Australia.

The battle began with the successful capture of the southern Solomon Islands by U.S. Marines but dragged on for many more months as the Japanese made repeated attempts to retake the island and its crucial airfield.

In the end, both sides incurred heavy losses of soldiers, ships, and aircraft. But unlike the U.S. forces, the Japanese could not sustain these losses and were forced on the defensive for the rest of the war.

The Allies In Disarray

Keystone/Getty ImagesPortrait of American Admiral Ernest J. King, who came up with the ambitious Guadalcanal Campaign.

By the summer of 1942, the Allied forces of the Second World War were in an unenviable situation. The Nazis were pushing the Red Army back into the Soviet Union in a march toward Stalingrad. Meanwhile, much of the Asia Pacific region was under Japanese rule, with China desperately attempting to fight back.

At this point, it had been nine months since the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor into oblivion. President Roosevelt called the attack "a date which will live in infamy," and Congress formally declared war on the Japanese Empire the next day.

The First Major American Pacific War Offensive

Although the United States was already involved in the Second World War with its support of Allies' defensive operations, the country had not yet initiated any offensive campaigns. The U.S. had declared neutrality at the war's onset in 1939, but officially declared war on European Axis powers in December 1941. It began rounding up Japanese-Americans in internment camps in February 1942, as it feared a Japanese invasion of the U.S.

But the U.S. could no longer deny the growing Japanese threat. Japan controlled much of the Asia Pacific region and even planned to invade Australia. In fact, military intelligence reported that the Japanese were constructing an airfield on Guadalcanal they could use to aid their invasion. In America's eyes, an offensive move into the Pacific was crucial.

So the chief of U.S. Naval Operations Admiral Ernest J. King devised a massive offensive campaign, which would come to be known as the Guadalcanal Campaign. The plan was to take over the Solomon Islands, with Guadalcanal as a base, to stem the Japanese advance.

The "concept of operations," King wrote, "is not only to protect the line of communications with Australia," but to establish a series of "strongpoints from which a step-by-step, general advance can be made" by the Allies through the stretch of island territories that would eventually lead to Japan itself.

King, who was revered as a brilliant strategist, argued that the loss of four Japanese carriers at the Battle of Midway had done plenty of damage to halt Japanese Imperial forces in the Pacific, which meant this was an opportune time for the U.S. to take the strategic initiative.

Although skeptical at first, other military leaders and President Roosevelt were convinced of King's plan, and thus, the Guadalcanal Campaign was launched.

'Operation Shoestring'

The codename for the Guadalcanal invasion was "Operation Watchtower." But the Marines coined their own nickname for it: "Operation Shoestring," since most of the men involved were fresh from military training, and their supplies were limited.

Many of the U.S. high commanders were wary of the efforts needed to pull off the Pacific strategy. General Alexander Vandegrift, commander of the 1st Marine Division, wanted at least six months of training so his men could get used to the unchartered waters of the Pacific before launching the Guadalcanal campaign.

Meanwhile, Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher was dismayed that his ships would have to remain on station to resupply the Marines, which essentially meant they would be sitting ducks in the narrow waters of the slot. Similarly, Admiral Robert L. Ghormley, commander in the South Pacific, was worried about the lack of logistics and scarce mapping of the Pacific waters.

But Admiral King, the mind behind the Guadalcanal Campaign, remained adamant that the operation would work, "even on a shoestring."

The Battle Of Guadalcanal

PhotoQuest/Getty ImagesView of the destoyer USS Buchanan (DD-484) (left) as it refuels from the aircraft carrier USS Wasp (CV-7) while en route to Guadalcanal. The Wasp was sunk by Japanese torpedoes a month and a half after the picture was taken.

In late July, U.S. forces assembled near Fiji to prepare their capture of Guadalcanal, the largest of Britain's Solomon Islands protectorate. Japanese troops, with the help of conscripted workers from Korea, were constructing an airstrip at Lunga Point under the command of General Harukichi Hyakutake.

About 11,000 U.S. Marines descended on the shores of Guadalcanal island during the invasion, quickly gaining control of the island.

Most importantly, the U.S. Navy seizedthe Japanese airfield and renamed it Henderson Field. This airstrip would become the focal point of the battle for the next six months.

The nearby islands of Tulagi and Florida were also captured during the campaign with 3,000 Marines.

The Guadalcanal Campaign thus became the first American military offensive of World War II – and its first amphibious invasion since 1898. But despite initial successes, the Battle of Guadalcanal would prove to be a nightmare for the Allies.

An Inhospitable Environment

Not only did soldiers have to fight off the constant bombardment from enemy forces, but they also had to fight off the heat and hunger that came with the island's harsh, remote environment.

High temperatures, humid air, and wet jungles dampened proved both physically and mentally challenging for the Marines, and made food rations go bad. To top it off, an epidemic of malaria and skin disease also invaded the Allied troops.

In a report of the battleground environment, LIFE magazine described Guadalcanal's harsh terrain as such:

"The jungle is a solid wall of vegetable growth, a hundred feet tall. There are huge palm leaves, elephant-ear leaves of the taro, ferns and jagged leaves of the banana trees all tangled together in a fantastic web. Near the ground are thousands of kinds of insects, praying mantises, ants and spiders....In such hot, damp weather mosquitoes live luxuriantly. Sometimes they imbed themselves so deeply in the soldiers' flesh, they have to be cut out."

Keystone/Getty ImagesAmerican marines manning a Japanese field gun emplacement which they captured on Guadalcanal.

Malnourishment And Disease

Many of the U.S. Marines on the island, already malnourished from the hardships of the Great Depression, were becoming increasingly emaciated. Some soldiers lost as many as 40 pounds from malnutrition and disease.

In fact, it is estimated that only one-third of the injured Marines on Guadalcanal were hurt by enemy fire; two-thirds of Marines suffered from tropical diseases.

It didn't help that a rumor had spread among soldiers that taking Atabrine — an anti-malaria drug — would make them sterile. By the end of 1942, more than 8,000 men of the 1st Marine Division had malaria.

Brutal conditions on the island were compounded by daily Japanese bombardments. The battle of Guadalcanal would wage on for six months, resulting in long stretches without action — until the destructive air raids would suddenly come. These quiet stretches at times caused the soldiers to grow complacent to the threat of an attack.

The Tokyo Express

Keystone/Getty ImagesHenderson Field in smouldering ruins after a Japanese air attack.

The sudden invasion by American forces caught the Japanese by surprise. Japan knew that without reinforcements their 2,000-soldier island garrison wouldn't last, so it began to hatch a plan to bring in more resources and launch a counterattack.

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) eventually brought reinforcements on a heavily-escorted convoy in what the marines dubbed the "Tokyo Express." The convoy ran from Rabaul, Papua New Guinea and the nearby Shortland Islands down the New Georgia Sound, which became known as "the slot."

The operation brought 1,000 Japanese troops to the island per night, escorted by seven fleet destroyers, heavy cruisers and air support. The soldiers worked efficiently under the cover of darkness, and by daylight, the Japanese troops were replenished and ready to fight.

One of the main reasons for the success of the Express was the dutiful command of Rear Admiral Raizo Tanaka. A highly decorated Japanese naval commander, Tanaka was so revered by both his comrades and enemies that he earned the nickname Tanaka the Tenacious.

A Deadly Japanese Armada

The Tokyo Express was feared under Tanaka's leadership. As James Hornfischer wrote in his book Neptune's Inferno: The U.S. Navy at Guadalcanal, an officer aboard the San Francisco flagship cruiser overheard a conversation between U.S. Rear Admiral Daniel Callaghan and Captain Cassin Young discussing the possibility of confronting Japan's heavily armed convoy:

"They were discussing the unannounced fact that there were battleships in the Tokyo Express... Captain Young...was in an understandably agitated state, sometimes waving his arms, as he remarked, 'This is suicide.' Admiral Dan Callaghan replied, 'Yes, I know, but we have to do it.'"

In fact, the idea of confronting the Express was so frightening that their ship's crew began to believe they were on a suicide mission. "We all were prepared to die. There was just no doubt about it," said seaman Joseph Whitt. "We could not survive against those battleships."

There was no doubt that the Tokyo Express played a huge part in Japan's stronghold in the Pacific.

Once dusk came, the Japanese Tokyo Express would race through the "slot" to Guadalcanal. By fall, the Tokyo Express had delivered some 20,000 men and equipment and would continue to steadily supply IJN forces well into 1943.

The Battle Of Savo Island

Less than two days after the launch of the U.S.'s Guadalcanal Campaign, on the night of August 8-9, the first naval engagement of Guadalcanal began with the Battle of Savo Island. The battle was the first of several major clashes that would take place on land and in the waters around Guadalcanal.

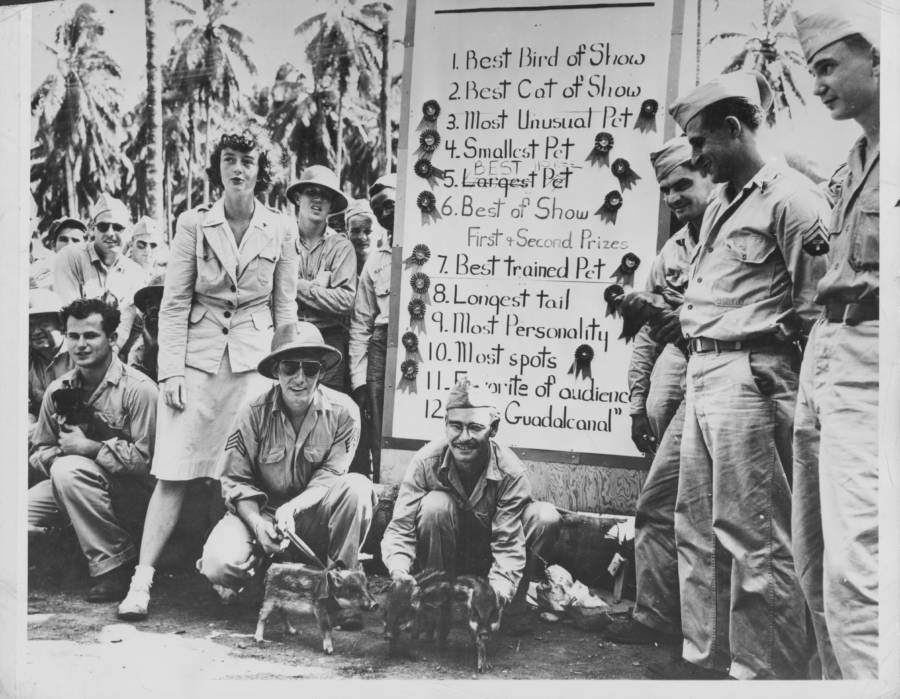

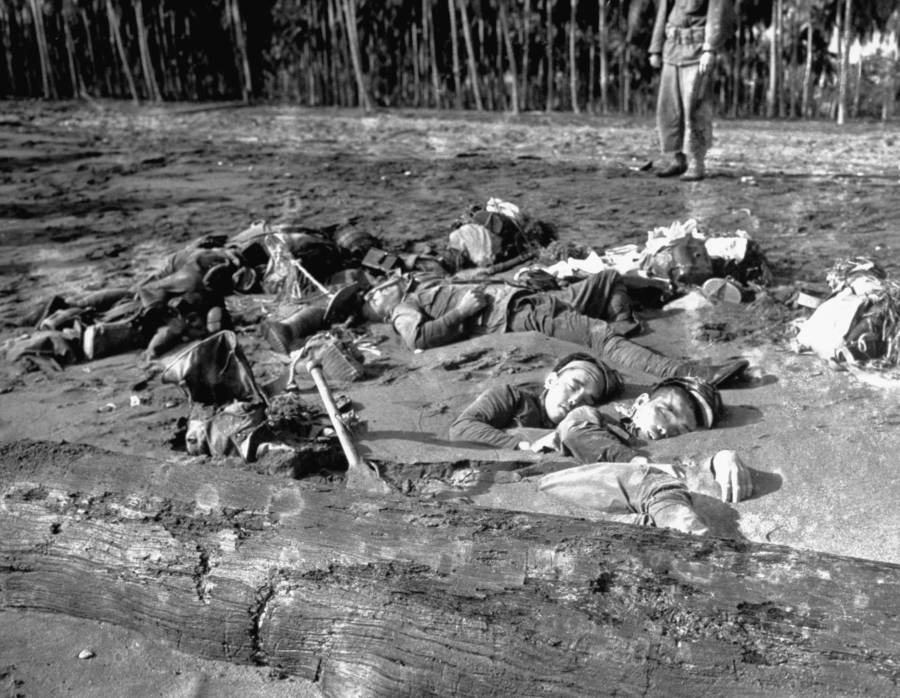

Time Life Pictures/US Marine Corps/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty ImagesBodies of Japanese soldiers who tried to overrun the U.S. marine positions on the island's coast, lying half-buried in the sandy banks.

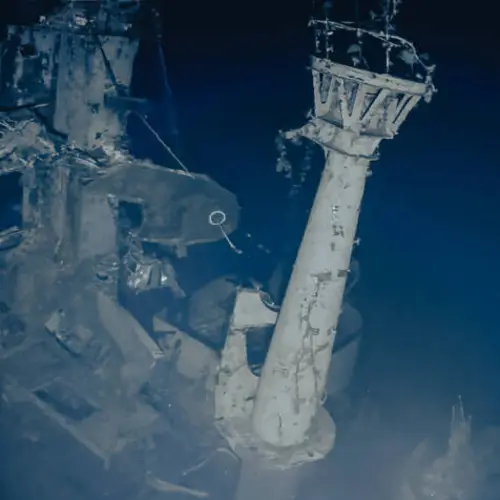

The battle at Savo was fought within the stretch of water between Guadalcanal and Tulagi, later known as "Ironbottom Sound" due to the number of battleships destroyed and sunk there.

The Allies lost 1,023 men — nearly 10 times as many as Japan did. Seven hundred Americans were wounded. Much of the U.S.'s cruiser-destroyer force was ruined at Savo, leading to the Navy's suspension of all transportation to the island. Marines were left stranded without few supplies.

One researcher called Savo "the most lopsided defeat in U.S. Navy history." But it was only the beginning of the Guadalcanal Campaign.

Getty ImagesAxis propagandists argued that U.S. Marines took no prisoners, despite photographic evidence that prisoner cages were present on the island.

Battle Of The Tenaru

The IJN's first attempt to retake Guadalcanal was in the Battle of the Tenaru, also known as the Battle of Alligator Creek or the Battle of the Ilu River, on August 21, 1942. Under the command of Japanese Colonel Kiyonao Ichiki, the IJN conducted a frontal assault against U.S. forces in the dead of night.

Just after midnight, the Japanese arrived at Alligator Creek, near the Henderson airfield the Americans had taken weeks earlier. The Japanese eventually fired machine guns and charged across the sand bar in an attempt to recapture the field, but were met with brutal enemy fire.

"It was an experience which was loud, glaring, confusing, bloody, overwhelming. But the fear diminished when it became a life struggle. Dead bodies were everywhere," recalled Marine veteran Arthur Pendleton.

The Japanese tried the same strategy again, only to incur further losses. Then, as a last-ditch effort, they made their way to the water and tried to pounce on the Americans by sea — but they were met with just as much gunfire. By daybreak, the Japanese were crushed.

The Japanese had underestimated the U.S.'s strength and suffered great losses — roughly 900 Japanese soldiers were killed in the battle. Colonel Ichiko himself died that day, either by enemy fire or by ritual suicide, ashamed of his loss. It was the first of three separate major land offensives by the Japanese in the Guadalcanal Campaign.

The U.S. continued their clashes with the Japanese on multiple fronts surrounding Guadacanal Island in order to complete the Allies' takeover of the Pacific. Notable conflicts occurred in the Battle of the Eastern Solomons, the Battle of Edson's Ridge, and the Battle of Cape Esperance, among several others during the Guadalcanal Campaign.

Conflicts Over Henderson Field

Wikimedia CommonsAn aerial view of Henderson Field. The U.S. and Japan constantly jockeyed for control over Guadalcanal's precious airstrip.

It was obvious that Henderson Field — the only airstrip in the region — was the key strategic point of the Battle of Guadalcanal. The fight for control of this airfield reached a new ferocity on the night of October 14, when the Japanese battleships Haruna and Kongō opened fire.

The ships dropped two-ton shells as large as a Volkswagen Beetle around the American-held Henderson Field, destroying runways, aircraft, and injuring soldiers. "We were laying down in our pillbox. A whistling noise and then boom!" Pharmacist's Mate 1st Class Louis Ortega, who was at Henderson Field that night, recalled.

"And then another one. For the next four hours, we were bombarded by four battleships and two cruisers. Let me tell you something. You can get a dozen air raids a day but they come and they're gone. A battleship can sit there for hour after hour and throw 14-inch shells. I will never forget those four hours."

After the shelling, American Seabees (Naval construction crews) repaired the damages to the airfield and substitute aircraft and drums of fuel were — slowly — flown into the base. But physical destruction was not the only thing that had been left in the wake of Japan's attack.

There were accounts of men emerging from their dugouts shaking violently with ears bleeding, their hearing destroyed and their vision blurred. Many also suffered from blast concussions that rendered them disoriented for days after the attack.

Even for veterans of the bloody Tenaru River and Edson's Ridge battles, the October 14 raid was by far the most frightening of the Guadalcanal Campaign.

Nearing The End Of The Guadalcanal Campaign

In mid-November of 1942, after more than three months battling for control of the Solomon Islands, Japan and the U.S. engaged in the decisive battle of Guadalcanal: the Naval Battle. Both sides incurred heavy losses, including soldiers and warships, but the Americans ended up on top.

Even after heavy artillery and multiple assaults by land and sea, Japan was unable to wrench control of Henderson Field from the Americans. With no airstrip, Japan was forced to replenish supplies by boat via the Tokyo Express, which wasn't enough to sustain its troops. And thus, in December, it began to pull out of Guadalcanal.

By the end of the Battle of Guadalcanal, the Japanese had lost about 19,000 of their 36,000 army troops (many of them to disease and malnutrition), 38 ships, and 683 aircraft.

Although the Allies fared better, the Guadalcanal campaign was a costly endeavor for them too: They lost about 7,100 out of 60,000 men, 29 ships, and 615 aircraft.

The Thin Red Line

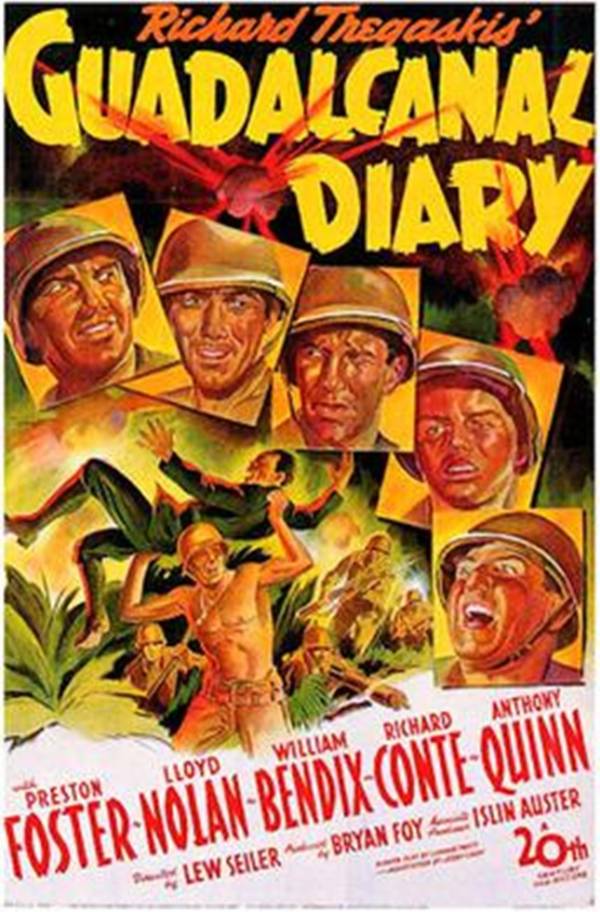

Many filmmakers have tried to retell the story of the Guadalcanal Campaign. One of the very first attempts at bringing the Pacific struggle to the screen was Guadalcanal Diary, which was based off the memoir of war correspondent Richard Tregaskis, and was published the same year the campaign ended.

But the most famous recreation of the battle is the 1998 film The Thin Red Line. Featuring a star-studded cast including John Travolta, Woody Harrelson, George Clooney, and Sean Penn, the film ranks number 10 on the Guardian's "25 Best Action and War Films of All Time" list.

The Thin Red Line was directed by Terrence Malick, who had no experience or interest in making a war film according to post-production anecdotes from the cast and crew.

"He never expected it to be this big thing with loads of men and machines," actor Ben Chaplin said in an interview with EW. "He had written this film about people and nature, and he got here and there was this war going on."

Other members of the film's cast spoke of similarly "abstract" and "spontaneous" experiences of shooting the war epic. Malick's take on the brutalities of the Guadalcanal Campaign came with a hefty $52 million price tag.

Wikimedia CommonsPoster for the 1943 film Guadalcanal Diaries, which came out the same year the horrendous battle occurred.

James Jones: Bringing Guadalcanal To Life

The Thin Red Line was based on the 1962 novel of the same name by James Jones, who served in the Battle of Guadalcanal. But even in Jones' own preface to his novel, he admits the world in his book was created from his imagination rather than a true depiction of the Pacific battlefield.

Despite the liberties that Jones may have taken in his book, it is still infused with the realness of his own experience and that of thousands of others who lived through the horrors of the battle. His novel remains one of the most powerful pieces of literature on the topic of war.

"The thing my father never got over was a Japanese soldier that he had killed in hand-to-hand combat in Guadalcanal," said Kaylie Jones, daughter of the late writer and veteran. "The thing that he said was that he had the same things in his wallet. He was the same as this [Japanese] man."

Ultimately, despite all the heroism and sacrifice on both sides, it was statements like these that best described the tragic futility of the Battle of Guadalcanal and war as a whole.

Next, take a look inside Truk Lagoon, World War II's most haunting undersea graveyard. And then, read about the worst war crimes the U.S. committed during the war.