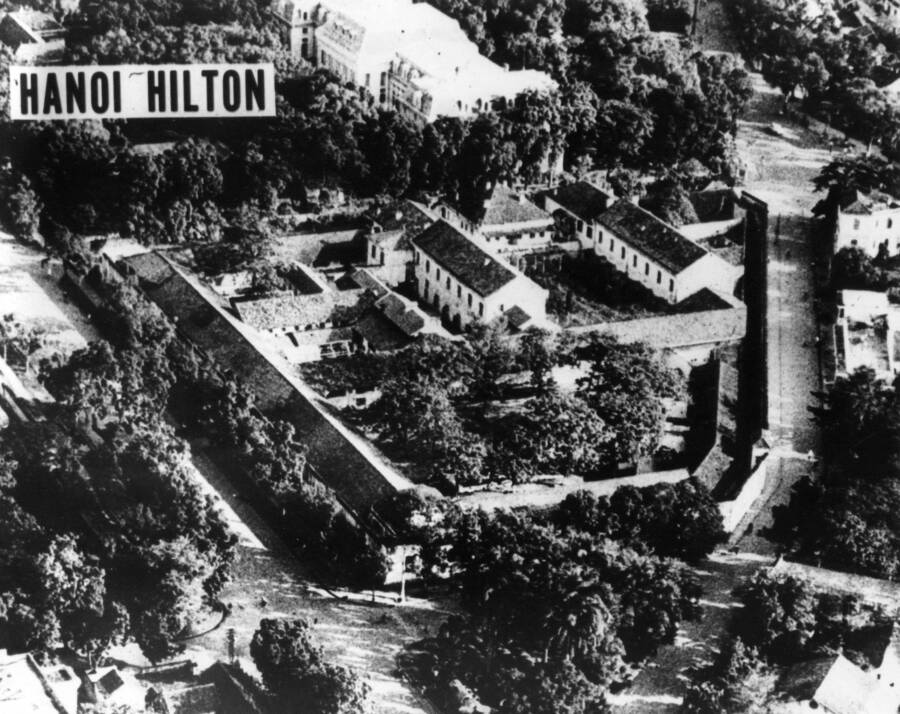

The North Vietnamese called it the Hỏa Lò prison, while American POWs ironically dubbed it the "Hanoi Hilton." Hundreds were tortured there with meat hooks and iron chains — including John McCain.

In the North Vietnamese city of Hanoi, hundreds of American soldiers were captured and kept prisoner in the Hỏa Lò prison, which the Americans ironically dubbed the “Hanoi Hilton.”

Far from a luxury hotel, here the prisoners of war were kept in isolation for years on end, chained to rat-infested floors, and hung from rusty metal hooks.

At the end of the war, these soldiers were finally freed from their own personal hell, many of them — including the late Arizona Senator John McCain — going on to become prominent politicians and public figures.

But others were not so lucky. As many as 114 American POWs died in captivity during the Vietnam War, many within the unforgiving walls of the Hanoi Hotel.

The History Of The Infamous Hanoi Hilton

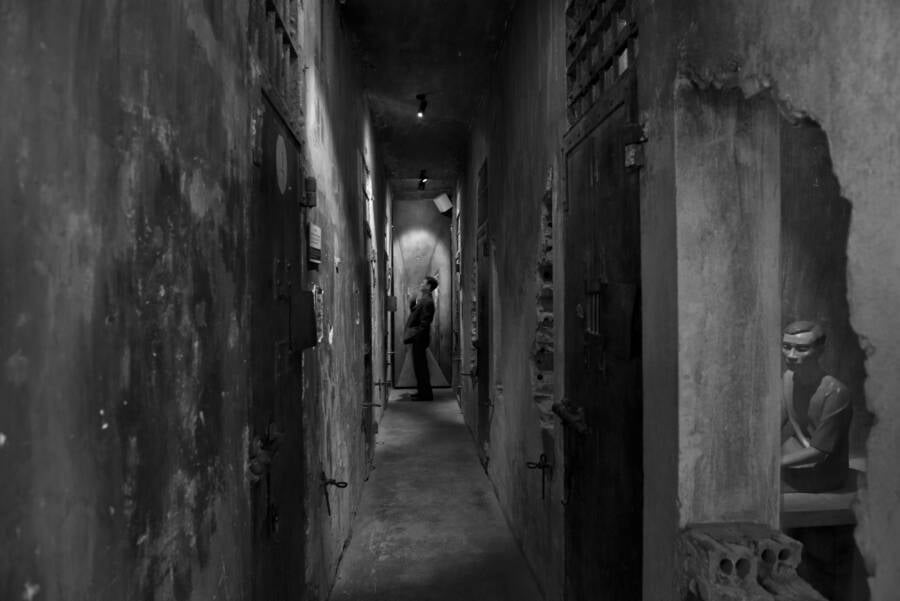

Rio Helmi/LightRocket/Getty ImagesDuring the French colonial period, Vietnamese prisoners were detained and tortured at the Hỏa Lò prison. During the Vietnam War, the North Vietnamese did the same to American soldiers.

Before the American prisoners gave the prison its now-infamous name, the Hanoi Hilton was a French colonial prison called La Maison Centrale. The Vietnamese, however, knew it as the “Hỏa Lò” Prison, which translates to “fiery furnace.” Some Americans called it the “hell hole.”

Built in the late 19th century, Hỏa Lò originally held up to 600 Vietnamese prisoners. By 1954, when the French were ousted from the area, more than 2,000 men were housed within its walls, living in squalid conditions.

By the time the Americans sent combat forces into Vietnam in 1965, the Hỏa Lò Prison had been reclaimed by the Vietnamese. They were finally free to put their enemies behind its bars, and American soldiers became their prime targets.

The Torture Of American Soldiers At Hỏa Lò

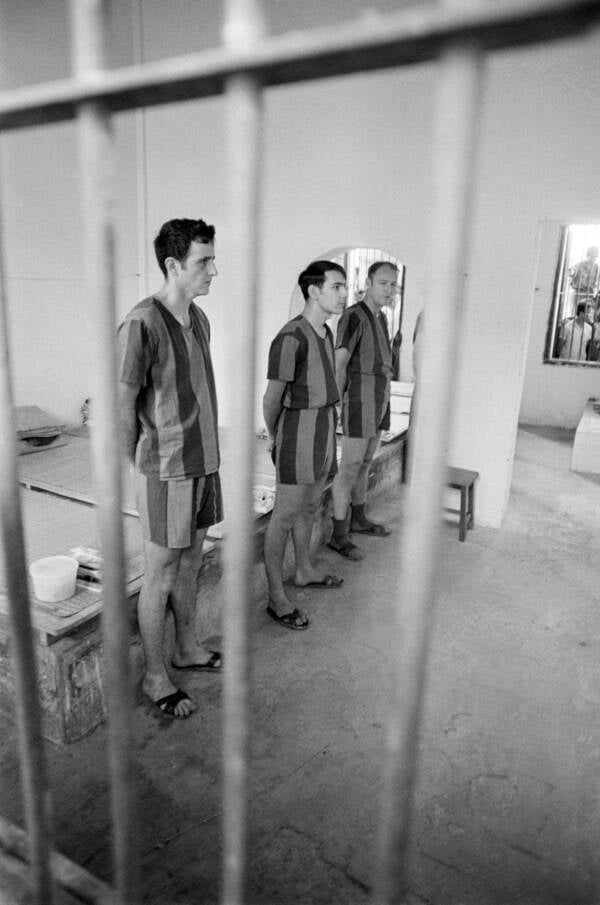

David Hume Kennerly/Getty ImagesAmerican POW soldiers line up at the Hanoi Hilton prior to their release. March 29, 1973.

Over nearly a decade, as the U.S. fought the North Vietnamese on land, air, and sea, more than 700 American prisoners of war were held captive by enemy forces. For those locked inside the Hanoi Hilton, this meant years of daily torture and abuse.

In addition to extended solitary confinement, prisoners were regularly strapped down with iron stocks leftover from the French colonial era. Made for smaller wrists and ankles, these locks were so tight that they cut into the men’s skin, turning their hands black.

Locked and with nowhere to move — or even to go to the bathroom — vermin became their only company. Attracted by the smells and screams, rats and cockroaches scurried over their weak bodies. Prisoners were forced to sit in their own excrement.

They were also viciously beaten and forced to stand on stools for days on end.

As Cmdr. Jeremiah Denton later said, “They beat you with fists and fan belts. They warmed you up and threatened you with death. Then they really got serious and gave you something called the rope trick.”

Prisoner Sam Johnson, later a U.S. representative for nearly two decades, described this “rope trick” in 2015:

“As a POW in the Hanoi Hilton, I could recall nothing from military survival training that explained the use of a meat hook suspended from the ceiling. It would hang above you in the torture room like a sadistic tease — you couldn’t drag your gaze from it.

During a routine torture session with the hook, the Vietnamese tied a prisoner’s hands and feet, then bound his hands to his ankles — sometimes behind the back, sometimes in front. The ropes were tightened to the point that you couldn’t breathe. Then, bowed or bent in half, the prisoner was hoisted up onto the hook to hang by ropes.

Guards would return at intervals to tighten them until all feeling was gone, and the prisoner’s limbs turned purple and swelled to twice their normal size. This would go on for hours, sometimes even days on end.”

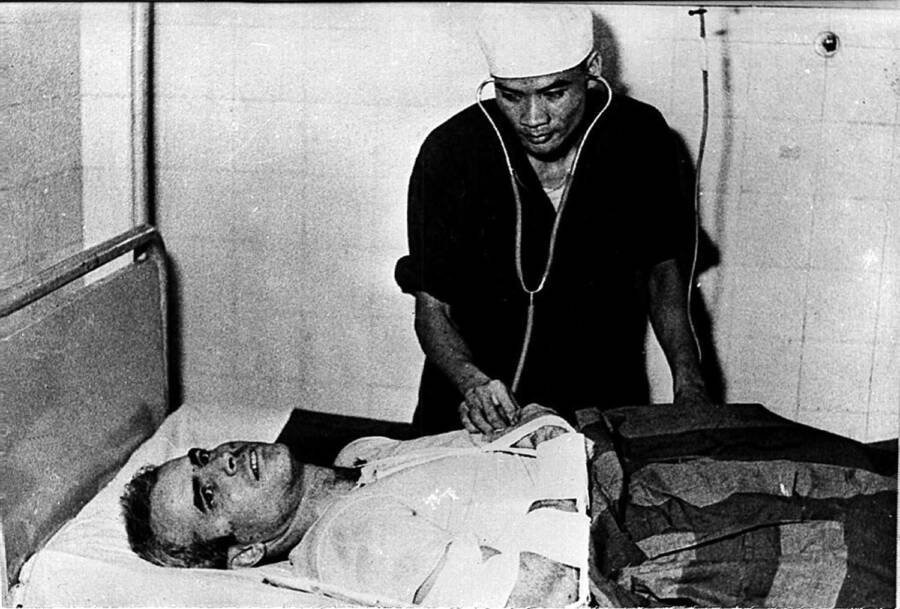

AFP/Getty ImagesJohn McCain was captured in 1967 at a lake in Hanoi after his Navy warplane was been downed by the North Vietnamese.

In 1967, McCain joined the prisoners at the Hanoi Hilton after his plane was shot down. His right knee and arms were broken in the crash, but he was denied medical care until the North Vietnamese government discovered that his father was a U.S. Navy admiral.

He was transferred to a medical facility and woke up in a room filthy with mosquitoes and rats. Finally, they set him in a full-body cast, then cut the ligaments and cartilage from his knee.

Even when the North Vietnamese offered McCain an early release — hoping to use him as a propaganda tool — McCain refused as an act of solidarity with his fellow prisoners.

This, of course, earned him additional torture. During his time at the Hanoi Hilton, McCain’s hair turned completely white.

American Resistance In Hỏa Lò Prison

David Hume Kennerly/Getty ImagesAmerican POW soldiers inside their jail cell at the Hanoi Hilton prior to their release. March 29, 1973.

Despite the endless torture, the American soldiers stayed strong the only way they knew how: camaraderie.

During his first four months in solitary confinement, Lt. Cmdr. Bob Shumaker noticed a fellow inmate regularly dumping his slop bucket outside. On a scrap of toilet paper that he hid in the wall by the toilets, he wrote, “Welcome to the Hanoi Hilton. If you get note, scratch balls as you are coming back.”

The American soldier followed his instructions, and even managed to leave his own note, identifying himself as Air Force Capt. Ron Storz.

This was one of many ways POWs figured out how to communicate. They eventually decided on using the “tap code” — something that couldn’t be understood by North Vietnamese forces.

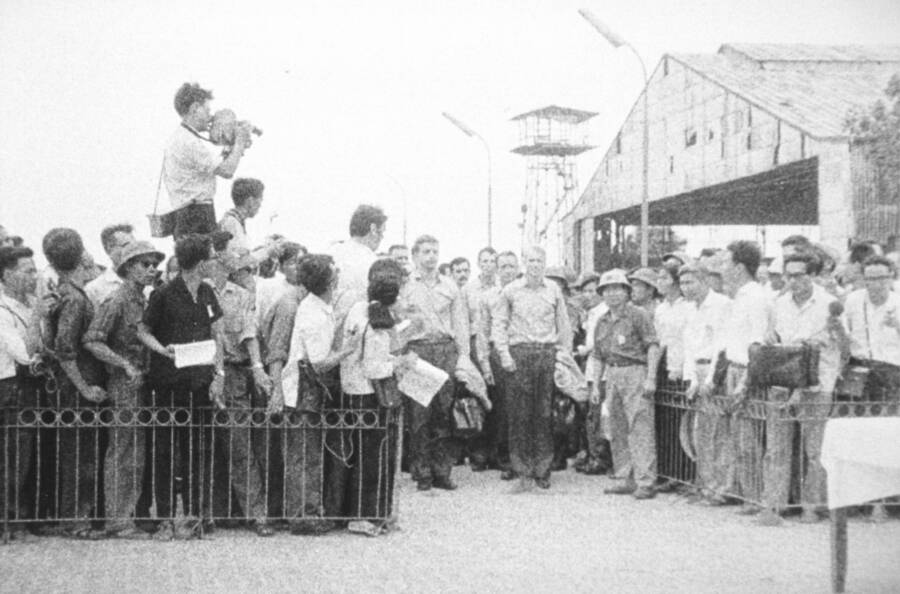

Usaf/Getty ImagesJohn McCain, leads a column of POW’s released from the Hanoi Hilton, awaiting transportation to Gia Lam Airport. March 14, 1973.

By tapping on the prison walls, the prisoners would warn each other about the worst guards, explain what to expect in interrogations, and encourage each other not to break. They even used this code to tell jokes — a kick on the wall meant a laugh.

Air Force pilot Ron Bliss later said the Hanoi Hilton “sounded like a den of runaway woodpeckers.”

The ultimate example of Hỏa Lò Prison resistance was performed by Denton. Taken before TV cameras in order to film antiwar propaganda for the North Vietnamese, Denton blinked the work “torture” in Morse code — the first evidence that life at the Hanoi Hilton was not what the enemy forces made it seem.

U.S. officials saw this tape and Denton was later awarded the Navy Cross for his bravery.

Finally, after the U.S. and North Vietnam agreed to a ceasefire in early 1973, the 591 American POWs still in captivity were released.

“‘Congratulations, men, we just left North Vietnam,'” former POW David Gray recalled his pilot saying. “And that’s when we cheered.”

What Happened To The Horrific Prison?

Wikimedia CommonsThe Hanoi Hilton in 1970.

That delightful day in 1973 would not be the last time that some of the prisoners would see the Hanoi Hilton.

John McCain returned to Hanoi decades later to find that most of the complex had been demolished in order to make room for luxury high-rise apartments. The rest became a museum called the Hỏa Lò Prison Memorial.

Most of the museum is dedicated to the building’s time as the Maison Centrale, the colonial French prison, with cells on display that once held Vietnamese revolutionaries. There’s even an old French guillotine.

Only one room in the back is dedicated to American POWs, though it doesn’t make any reference to torture — there are even videos detailing the “kind treatment” of the prisoners alongside photos of Americans playing sports on the prison grounds.

What’s more, the museum displays a flight suit and parachute labeled as belonging to McCain, from when he was shot down over Hanoi — except they’re fake.

Wikimedia CommonsJohn McCain’s alleged flight suit and parachute, on the display at the former Hanoi Hilton.

“They cut my flight suit off of me when I was taken into the prison,” McCain said. “The ‘museum’ is an excellent propaganda establishment with very little connection with the actual events that took place inside those walls.”

But McCain, for one, still came to terms with his time at the horrific Hanoi Hilton.

“Forty years later as I look back on that experience, believe it or not, I have somewhat mixed emotions in that it was a very difficult period,” he said in 2013. “But at the same time the bonds of friendship and love for my fellow prisoners will be the most enduring memory of my five and a half years of incarceration.”

After reading about the gruesome conditions that awaited American POWs in the Hanoi Hilton, read about the Gulf of Tonkin incident, which first sparked the Vietnam War. Then learn take a look inside the Andersonville Prison, a brutal POW camp during the Civil War.