Decades before the Holocaust, the German Empire committed the 20th century's first genocide.

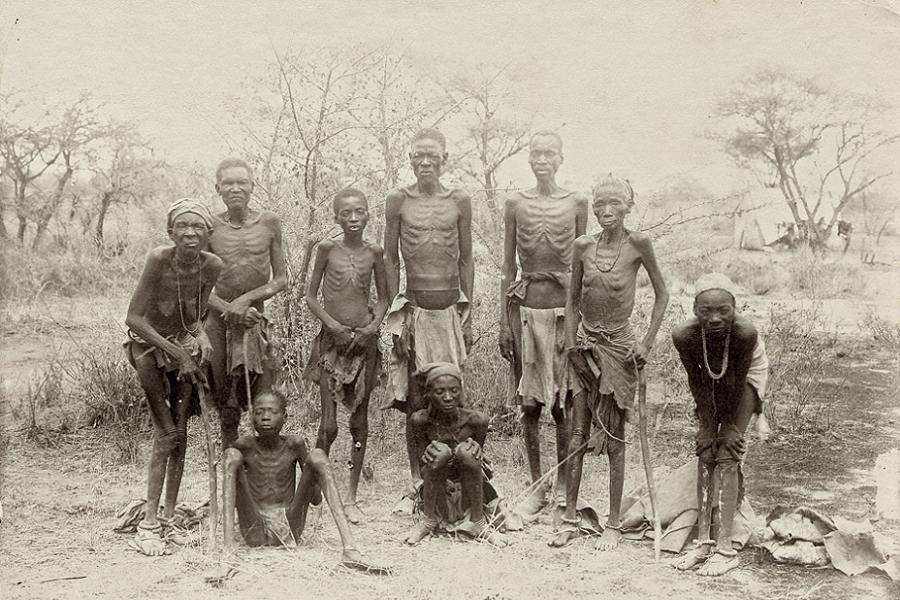

Wikimedia CommonsHerero chained during the 1904 rebellion.

Once upon a time, German soldiers and settlers poured into a foreign country and seized the land for themselves. To make sure they could hold on to it, they destroyed local institutions and used existing divisions among the people to prevent organized resistance.

By force of arms, they transported ethnic Germans into the territory to extract resources and to rule over the land with a coarse and brutal efficiency. They built concentration camps and filled them to the brim with whole ethnic groups. Huge numbers of innocents died.

The damage from this genocide still lingers, and the families of survivors have sworn never to forget the German effort to destroy them as a people.

If you thought that description applied to Poland during World War II, you’re right. If you read it and thought of Namibia, the former colony of German Southwest Africa, you’re also right, and it’s likely you’re a historian who specializes in African studies, because the German reign of terror against the Herero and Nama people of Namibia hardly gets mentioned outside of scholarly literature.

Widely considered to be the first genocide of the 20th century, long denied and suppressed, and with endless bureaucratic paper chases to prevent a reckoning, the Herero genocide – and its modern legacy – deserves more attention than it’s received.

The Scramble for Africa

Wikimedia CommonsDelegates reach agreement at the 1878 Berlin Congress, where the fate of Africa was decided entirely by European negotiators.

In 1815, as far as Europe was concerned, Africa was a dark continent. Except for Egypt and the Mediterranean coast, which had always been in contact with Europe, and a small Dutch colony in the south, Africa was a complete unknown.

By 1900, however, every inch of the continent, except for the American colony in Liberia and the free state of Abyssinia, was ruled from a European capital.

The late 19th century scramble for Africa saw all of the ambitious powers of Europe snatching as much land as possible for strategic advantage, mineral wealth, and living space. By the end of the century, Africa was a calico of overlapping authorities where arbitrary borders cut some native tribes in two, jammed others together, and created the conditions for endless conflict.

German South-West Africa was a patch of turf on the Atlantic coast between the British colony of South Africa and the Portuguese colony of Angola. The land was a mixed bag of open desert, forage grassland, and some arable farms. A dozen tribes of various sizes and practices occupied it.

In 1884, when the Germans took over, there were 100,000 or so Herero, followed by 20,000 or so Nama.

These people were herders and farmers. The Herero knew all about the outside world and freely traded with European businesses. At the opposite extreme were the San Bushmen, who lived a hunter-gatherer lifestyle in the Kalahari Desert. Into this crowded country came thousands of Germans, all hungry for land and looking to get rich from herding and ranching.

Treaties and Treachery

Wikimedia CommonsHeinrich Ernst Göring, father of leading Nazi Hermann Göring, was Namibia’s first German governor and set the stage for much of the conflict that would follow.

The Germans played their opening gambit in Namibia by the book: Find a local bigwig with dubious authority and negotiate a treaty with him for whatever land desired. That way, when the land’s rightful owners protest, the colonists can point to the treaty and fight to defend “their” land.

In Namibia, this game started in 1883, when German merchant Franz Adolf Eduard Lüderitz purchased a tract of land near the Angra Pequena Bay in what is today southern Namibia.

Two years later, German colonial governor Heinrich Ernst Göring (whose ninth child, future Nazi commander Hermann, would be born eight years later) signed a treaty establishing German protection over the area with a chief named Kamaherero of the large Herero nation.

The Germans had all they needed to seize land and start importing settlers. One Herero fought back with weapons acquired through trade with the outside world, forcing the German authorities to admit to the shakiness of their claims, and eventually reach a sort of compromise peace.

The deal the Germans and Herero reached in the 1880s was an odd duck among colonial regimes. Unlike the colonies of other European powers, where the newcomers took whatever they wanted from the indigenous populations, German settlers in Namibia often had to lease their ranch land from Herero landlords and trade on unfavorable terms with the second-largest tribe, the Nama.

To the whites, this was an untenable situation. The treaty was renounced in 1888, only to be reinstated in 1890, and then enforced in a haphazard and unreliable way throughout the German holdings. German policy toward the natives ranged from hostility for the established tribes to outright favoritism for those tribes’ enemies.

Thus, while it took seven Herero witnesses to equal the testimony of a single white in the German courts, members of smaller tribes such as the Ovambo got lucrative trade deals and jobs in the colonial government, which they used to extract bribes and other favors from their ancient rivals.

Hunger for Land

Wikimedia CommonsMuch of Namibia is a mix of red sand dunes and open grassland. In marginal places, it can be difficult for cattle to find forage.

All of this confusion regarding treaties and tribal alliances was deliberate, and it operated against the backdrop of the Germans’ insatiable hunger for land. Namibia had been identified as the one German colonial possession suitable for large-scale settlement, and the ranching these German cowboys were doing might have been the most land-intensive operation in the world.

Namibia has some good forage land, which the Herero and Nama had taken for themselves centuries before, but it also has a lot of marginal scrub where a herd of cattle has to move all day to get enough food. The Germans, tired of paying Africans for grazing rights in the scrub, started talking about native reserves and mass deportations.

Their anger came out in various ways. German cattle regularly crossed imaginary boundaries to graze on Herero land, and it wasn’t uncommon for ranchers to shoot lone Herero they caught in the open.

Herero and Nama women caught near German claims were frequently raped, and German magistrates got in the habit of turning a blind eye to crimes that German settlers committed against the natives. Germans imposed taxes on some tribes for land they had lived on time out of mind, and German slavers made raids into the interior for domestic and farm labor.

By 1900, the German resentment of the Herero was more than matched by native hatred of the interlopers. Both sides began to arm for war.

Revolt and Conquest

Wikimedia CommonsA group of Herero pose for a picture after trekking through the desert for an unknown time after the Battle of Waterberg in August 1904.

When the war came, it was brief and brutal.

In January 1904, a Herero leader named Samuel Maharero put together a 5,000-man army and raised an insurrection. His troops were armed with an eclectic mix of state-of-the-art rifles and ancient war clubs. They traveled with as many as 50,000 civilians, mostly families, and slowly reclaimed lands they had lost to the Germans.

There was very little fighting, since isolated German families had no hope of resisting thousands of Herero fighting men, and by the end of winter, the rebels had taken most of the land they wanted.

That’s when the German administration suddenly got serious and appointed Lieutenant General Lothar von Trotha as governor. Von Trotha was a man with definite ideas about how to handle the Herero, and any other natives who seemed to be in the way of progress. In his own words:

“I wipe out rebellious tribes with streams of blood and streams of money. Only following this cleansing can something new emerge.”

He wasn’t joking. In August, von Trotha’s force of around 1,500 men, backed up by 30 field howitzers and 14 machine guns, pulverized the Herero force in the Battle of Waterberg. The fighting itself wasn’t terribly hard or destructive, but the German General Staff-trained von Trotha managed to block in the Herero on three sides with only the open desert at their backs.

After the clash, tens of thousands of Herero civilians took the one escape route that the Germans had left open, only to find that their enemy had sealed all of the wells between Waterberg and the desert. The victorious Germans formed a human barrier along a 150-mile front and shot every single Herero who crawled back in search of water.

The Herero genocide was underway as tens of thousands of people died of thirst in the wilderness, versus approximately two-dozen German dead during the whole operation, including the battle itself. The Herero and Nama who hadn’t been involved may have thought that things would now return to normal, but von Trotha was only getting started.

The Herero Genocide: Racial Hygiene and Germany’s First Concentration Camps

South African HistoryA German “hanging party” during the Herero genocide. The caption explains that 312 Herero were killed during the festivities.

Returning in triumph from Waterberg, von Trotha reinforced his garrison to 10,000 men and issued the following orders on October 2, 1904:

“All the Herero must leave the land. If they refuse, then I will force them to do it with the big guns. Any Herero found within German borders, with or without a gun, will be shot. No prisoners will be taken. This is my decision for the Herero people.”

Immediately after this proclamation, Germans seized all Herero lands and transferred all cattle to German ranchers. They drove the 50,000 remaining Herero into the wilderness, where they had them starved, shot at, and enslaved. They forced tens of thousands of Nama, whose tribe had also been hostile to the Germans, into the Germans’ new concentration camps.

There, beatings and rapes were a daily ordeal for the internees, who could be executed for any reason at all or at a guard’s whim. Raping the natives was officially frowned upon, but mixed-race children continued to be born in the camps.

German pathologists took an interest in this and descended on the camps to “prove” their racial theories with cognitive tests and grisly medical experiments that included dissection of freshly killed inmates.

Unsurprisingly, they “discovered” that the children of mixed blood were vastly superior to native Herero and Nama tribesmen, but still inferior to pure-white German children. Their findings made for several popular books on eugenics back in Europe, one of which, The Principles of Human Heredity and Race Hygiene, by Eugen Fischer, would later be read by Adolf Hitler during his 1923-25 prison term.

Aftermath and Reckoning Delayed

Flickr/SalymfayadA Herero woman poses next to an unmarried girl of the nearby Himba tribe in traditional dress.

Namibia was the place where Germany learned genocide, though that word hadn’t yet been coined. Between the summer of 1904 and spring of 1907, when public outcry forced von Trotha’s recall, the Imperial German Army had killed around 80,000 of the 100,000 Herero and 10,000 of the 19,000 Nama.

All of the good land in the country fell into German hands until after World War I, when the colony was awarded to the British. South Africa would continuously occupy the land until 1990.

Unsurprisingly, the white government of South Africa was in no hurry to acknowledge the Herero genocide. Facing their own racial problems back home, the colonial British authorities, and later the Afrikaner National Party, prevented investigation and discussion of the Herero genocide of 1904-07, and only started taking the matter seriously long after most of the firsthand witnesses were long dead.

This is just one of the many problems with getting a final reckoning for the Herero genocide. Germany has been through several changes of government since 1907, so it’s doubtful whether anyone in Europe can be held accountable for what happened to the Herero.

Descendants of the Herero genocide’s survivors now live on barren, crowded land, squeezed there by the favored tribes that weren’t herded into the camps. Those tribes, predominantly the Ovambo, have never been sympathetic to the Herero or the Nama, and so any settlement money that the Namibian government negotiates for is likely to be paid out among the very tribes that collaborated with the Germans, rather than to the descendants of the victims.

Finally, Namibia’s chief foreign-currency earner is German aid, which gives the government in the Namibian capital of Windhoek virtually no leverage in negotiations, even if it was serious about reparations for the Herero genocide in the first place.

Meanwhile, the modern Herero and Nama people scratch out a living in the veld, herding what cattle they have, farming where it’s possible, and half-subsisting on Namibia’s almost nonexistent social welfare programs. There seems to be no end in sight.

Atrocities like the Herero genocide aren’t isolated. Genocides have also taken place in the Congo as well as early 20th century Armenia.