The history of measles contains centuries of information. Here's what you need to know about the invasive, deadly disease.

Source: Etsy

Though the history of measles stretches across centuries, a recent measles outbreak at Disneyland has re-ignited interest in the illness. This brief history of measles (and vaccines) will give you a little perspective on just how far we’ve come, and what’s at stake as pseudoscientific arguments gain traction.

Physicians learned how to identify and diagnose measles between the third and ninth centuries. In the years that followed, measles would continue to spread around the world, aided by well-traveled explorers. Christopher Columbus and his comrades introduced many diseases to indigenous populations who lacked a natural immunity to them. In fact, measles (along with other illnesses like smallpox, whooping cough, and typhus) was responsible for wiping out as much as 95 percent of the Native American population.

Christopher Columbus lands in the Americas. Source: Wikipedia

From the ninth century to the 1900s, few events impacted the history of measles as much as these: In the mid-1700s, Scottish physician Francis Home realized that measles were caused by an infectious agent in the blood. In 1796, Edward Jenner successfully used cowpox material to create an immunity to smallpox.

Fast forward fifty years, when Danish physician Peter Ludwig Panum discovered that every individual who had previously been infected with measles was immune from catching the virus the second time around. Each of these medical discoveries was vital in putting an end to measles.

Source: Kickstarter

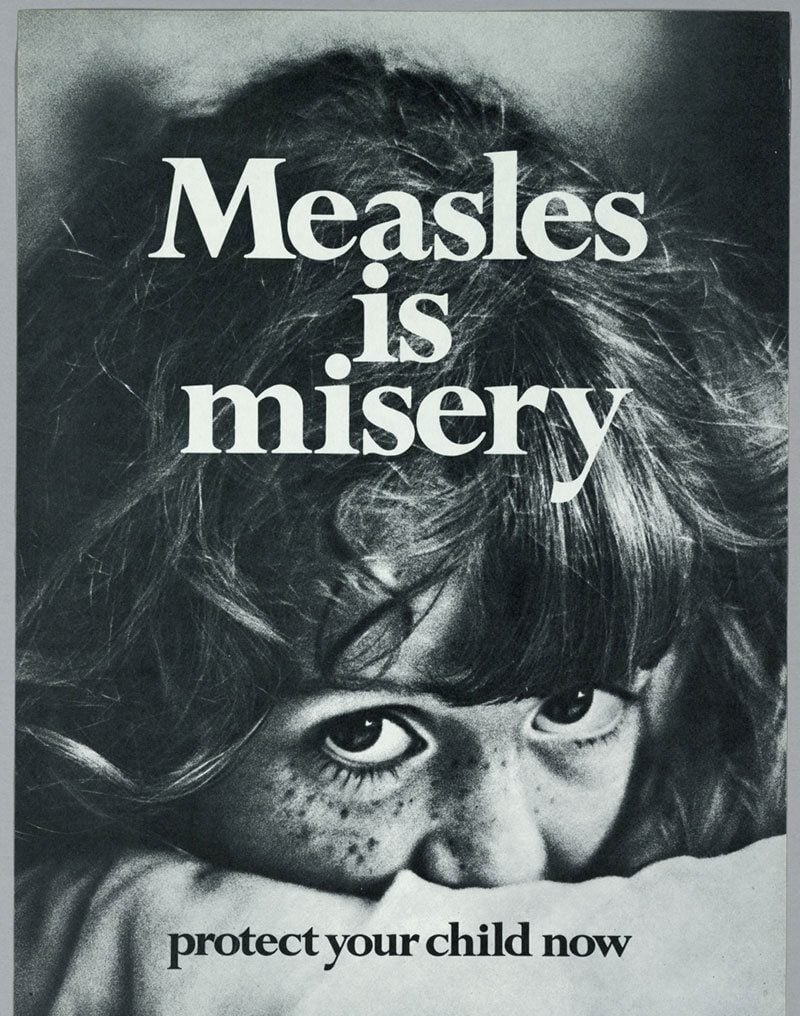

By 1912, the United States required healthcare providers to report all diagnosed cases of measles. In that time period, almost everyone suffered from the virus at some point in their lives, usually while they were young. For many, the disease was fatal. According to a study from 1912-1916, there were 26 deaths for every 1,000 people infected with measles. About 6,000 measles-related deaths were reported annually during 1912-1922.

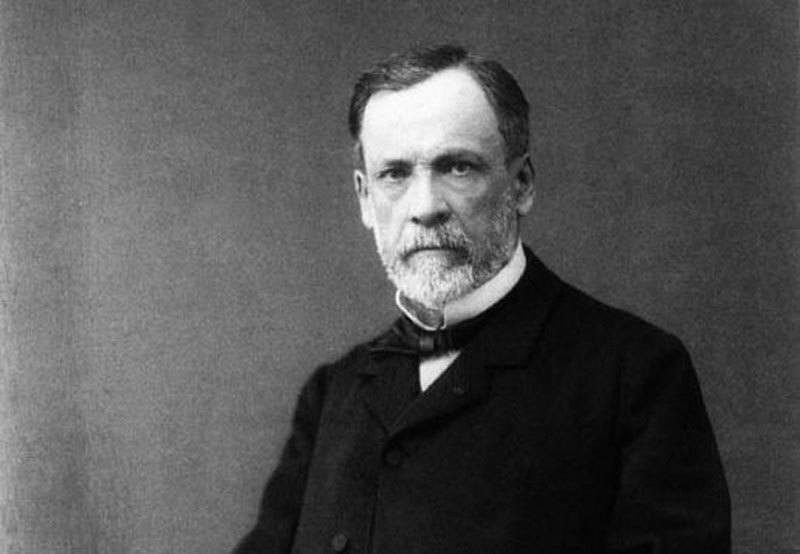

Louis Pasteur. Source: Pic13

In the decades that followed Louis Pasteur’s 1885 discovery of a rabies vaccine, a number of developments in bacteriology and immunology allowed physicians to understand (and prevent) many alarming diseases. Vaccines and antitoxins for tetanus, anthrax, cholera, typhoid and tuberculosis were all developed in the years leading up to the 1930s. By this time, vaccine research took center stage in medical circle. Yet there still wasn’t a vaccine for measles.

A 1963 virus laboratory. Source: NPR

In the 1950s, pretty much every child under the age of 15 had been infected with measles. From 1953 to 1963, an estimated 400 to 500 people died, 48,000 were hospitalized, and 4,000 suffered from a swelling of the brain—all brought about by measles.

Then a breakthrough came that greatly altered measles’ power. In 1954, John F. Enders and Dr. Thomas C. Peebles were able to isolate the measles virus in 13-year-old David Edmonston’s blood. In 1963, Enders used the Edmonston-B strain of the measles virus to create a vaccine that was licensed in the United States.

Source: Mercola

In 1968, Maurice Hilleman and his colleagues released a new and improved version of the measles vaccine. This strain, called the Edmonston-Enders strain, has been used in the United States since 1968. Eventually the measles, mumps and rubella vaccines were combined to create the MMR vaccine (called MMRV when combined with varicella). Measles was declared eliminated from the United States in 2000, saving countless lives.

Yet as the 2014 Disneyland outbreak proves, what is true in the United States is not the case for everyone, and even “endings” can be temporary. Modern outbreaks are almost always connected to those who travel to the US and infect unvaccinated individuals, often children.

Public health officials have yet to identify the index case in the Disneyland outbreak, but they feel it’s likely that that virus was caught abroad, and then distributed to children at the theme park.

Source: North Country Public Radio

While choosing not to vaccinate your child can seem like a good idea, once you look at the data, it’s pretty obvious that going sans vaccine is a very bad idea for everyone involved. Usually measles outbreaks occur among pockets of unvaccinated people, as they are incredibly vulnerable to the illness.

Though it’s too early to predict how the Disneyland measles outbreak will spread, it would be a shame to see the great advances made against the illness undermined by a cabal of quacks.

Source: Science Museum