How the H.L. Hunley, history's first combat sub, changed warfare forever — then vanished for over a century.

Getty images A sketch of the H.L. Hunley.

When one thinks of the Civil War, they’re probably more inclined to think of Gone With the Wind than epic submarine battles.

However, one little-known submarine battle did actually take place all the way back during the Civil War. Though the early submarine involved, the H.L. Hunley, wasn’t built to today’s standards, it changed the course of maritime warfare forever.

Before the H.L. Hunley was built, Confederate Army marine engineer Horace Lawson Hunley, along with fellow shipbuilders James R. McClintock and Baxter Watson, had already constructed the first Confederate submarine, the Pioneer, after hearing that the U.S. Navy was building one as well.

The trials for the Pioneer in New Orleans went well, but due to Union soldiers advancing on the city, Hunley and company were forced to abandon their efforts and scuttle their submarine prototype.

Not to be discouraged, the men tried again, this time building the American Diver. Similar in size and shape to the Pioneer, the American Diver was built in Mobile, Alabama, after Union forces had captured New Orleans.

However, the American Diver was ultimately a failure, as the men decided to try using an electrical motor, and later a steam engine, to power the sub. The weight of the materials made it impossible to achieve neutral buoyancy, and the men were forced to replace the engines with a hand crank. But due to the lack of power, the ship proved too slow for combat and ultimately ended up sinking when hit by a storm.

After their first two submarine attempts failed, the trio of shipbuilders split, and Hunley was left on his own. He continued researching his trade and mulling over his past failures until he eventually decided to give it one more shot.

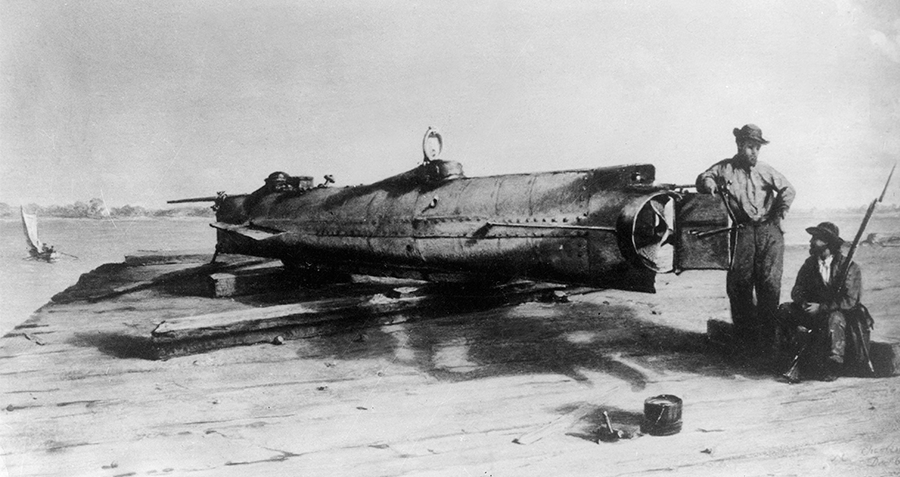

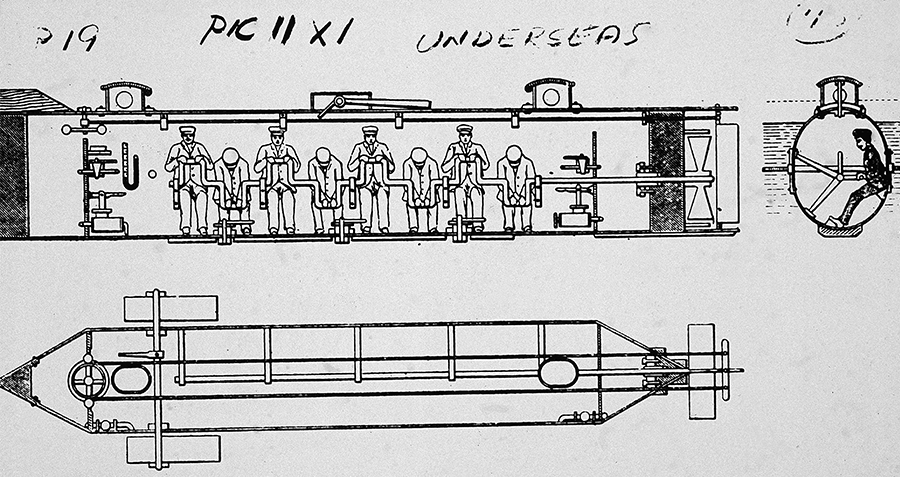

Hunley put together a torpedo-shaped submarine with two watertight hatches and a crew of eight. Like the American Diver, the submarine was powered by a hand-crank. However, Hunley theorized that with a larger crew, the necessary speed could be achieved.

But though more manpower meant more speed, it also meant that the conditions would be far worse for those men inside. They would spend much of their time rowing with little elbow room, hunched over the cranks.

Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesAn outline of what the interior of the H.L. Hunley looked like.

The H.L. Hunley Sees Its First Action

This new submarine, the H.L. Hunley, was finished in July 1863. Confederate Admiral Franklin Buchanan soon supervised the first-ever demonstration, during which the H.L. Hunley successfully attacked a coal flatboat in Mobile Bay. The submarine was deemed fit for service and sent by rail to Charleston, South Carolina.

Confederate Navy Lieutenant John A. Payne, who had previously commanded the CSS Chicora, volunteered to captain the H.L. Hunley, taking seven of his old crew members with him. They went out for their first test dive on Aug. 29, 1863.

As the crew members were preparing the crank, Lieutenant Payne accidentally stepped on the lever that controlled the diving planes, submerging the sub while her hatches were still open. Payne and two crew members were able to escape. However, the five other crew members drowned.

The Confederate Navy wasn’t happy that they had lost their sub, but one of the generals ordered that the submarine be raised, refurbished, and granted a new crew in Charleston. Payne himself decided to give the submarine another shot and joined the new crew, along with six other crewmen. To avoid any further mishaps, Hunley himself decided to join the new crew during a routine exercise.

The crew submerged the sub and attempted to perform a mock attack. However, something went awry, and the sub failed to surface, killing all seven men on board, including Hunley himself. Despite the sub’s now having sunk twice before it even saw combat, the Confederate Navy raised it again, determined to one day get some use out of it in combat.

Wikimedia CommonsArcheologists explore the interior hull of the H.L. Hunley.

That chance for combat came four months later. On the night of Feb. 17, 1864, the USS Housatonic sloop was floating five miles off the coast of Charleston, guarding the entrance to the city. A massive ship, the Housatonic could hold up to 18 guns and was manned by a crew of 150 men.

The Housatonic was a large part of the naval blockade preventing Confederate ships from entering the Union-controlled city of Charleston, and the Confederate army was desperate to break through.

Confederate Lieutenant George E. Dixon felt that his best chance at beating the Housatonic was by sea and chose the H.L. Hunley to be his vessel. Together with a crew of seven men, they took off for Charleston.

The H.L. Hunley was armed with a torpedo, a copper cylinder filled with gunpowder attached by a copper wire to a 22-foot-long wooden pole mounted on the front of the submarine. The idea was that the H.L. Hunley would jam the copper cylinder into the side of the Housatonic and then back away. When they were out of range, the copper wire could be used to detonate the cylinder.

The plan worked.

The H.L. Hunley successfully attacked the Housatonic, sinking it in five minutes. The crew that survived said that they didn’t even hear the explosion and only noticed the H.L. Hunley moments before, though they soon noticed the ship sinking and immediately entered the lifeboats.

As the Housatonic sank, the H.L. Hunley became the first submarine to sink an enemy warship in combat — and initiated what would eventually become international submarine warfare as we know it today.

While only five men went down with the ship, the loss of the Housatonic was still a blow for the Union Navy. Up until that point, they hadn’t considered the possibility of a near-invisible submarine attack, and they were forced to revisit their maritime warfare tactics.

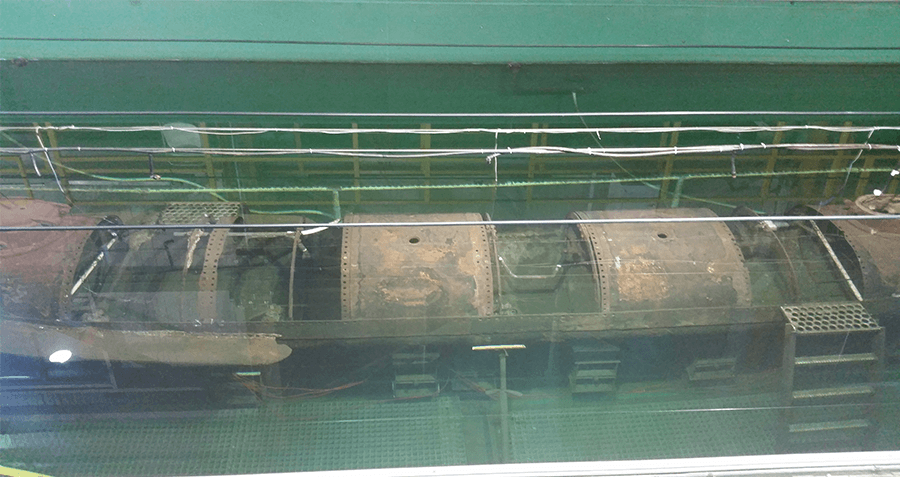

Wikimedia Commons The remains of the H.L. Hunley sit in a preservative sodium hydroxide bath.

The H.L. Hunley was riding high on the victory as it backed away from the sinking Housatonic — but the crew’s elation was to be short-lived. The submarine never made it back to its port on Sullivan’s Island, and it would be years before anyone discovered what happened to it.

Originally, the submarine was believed to have sunk as a result of the blast from its own torpedo during the battle, though some eyewitnesses claimed that it survived for more than an hour afterward.

A commander on Sullivan’s Island claimed that the H.L. Hunley sent a signal to Fort Moultrie after the Housatonic explosion and would not have been able to do so unless it had survived the battle.

Furthermore, a soldier who had been clinging to the rigging of the sunken Housatonic claimed to have seen a blue light, presumably that of the H.L. Hunley, drifting away from his shipwreck. After the war, soldiers stationed on Fort Moultrie claimed that two blue lights were the signal that the commander had mentioned.

However, many modern experts have claimed that there is no way a blue light could have come from the H.L. Hunley, as there were no blue lanterns aboard the submarine. Meanwhile, other experts claim that the “blue light” was not, in fact, a light of blue color, but a pyrotechnic symbol consisting of a quick flash of light, similar to a flare.

Either way, the alleged signal from the H.L. Hunley was the last time anyone heard from it for over 100 years.

Recovering The Hunley

Wikimedia CommonsThe H.L. Hunley hangs from a crane during its recovery from Charleston Harbor in 2008.

The recovery of the H.L. Hunley has been a matter of great dispute, with two separate parties claiming responsibility. In 1970, an underwater archeologist named E. Lee Spence claimed to have found the submarine and has a collection of evidence that seemingly validates him. The National Park Service also credited him with leading them to the site of the H.L. Hunley so it could be included in the National Register of Historic Places.

However, in 1995, a diver named Ralph Wilbanks happened upon the wreckage and announced it to the world as a new discovery. Though it was in fact not a new discovery, Wilbanks’s find pushed experts to start recovery efforts.

In 2000, the H.L. Hunley was officially removed from its century-old resting place. In the end, archeologists discovered that it had sunk just 100 yards from the Housatonic, leading them to believe that it had in fact been its own blast that took the H.L. Hunley down.

It had been buried under several feet of silt, which had protected the vessel from deteriorating as much as it otherwise could have, and it was in good condition when pulled out. After extensive research, the remains of the submarine were donated to the State of South Carolina and are currently on display at the Warren Lasch Conservation Center in Charleston.

Getty ImagesThe graves of the crew of the H.L. Hunley.

A memorial service was held for the crew in 2004 and their remains were laid to rest at Magnolia Cemetery in Charleston, where the single yet historic battle involving the H.L. Hunley took place some 150 years earlier.

After this look at the H.L. Hunley, read more about the human remains found aboard the Confederate submarine. Then check out these powerful Civil War photos.