Love led Horace Greasley to make over 200 escapes from German POW camps during World War 2.

Pte. Horace “Jim” Greasley.

Horace Greasley, known as Jim to his friends, joined the British army in 1939. His regiment landed in Normandy, and while the rest of the army retreated to Dunkirk, he and his comrades were ordered to stay behind and fight off the advancing Germans. Soon the exhausted regiment was cornered after they dared to grab a nap in a barn south of Lille, France.

They surrendered and were forced to march for ten weeks to Holland. Many of his fellow soldiers died during the trek; Greasley survived by eating plants and insects by the roadside, and by the food that the occasional villager would sneak to the men as they passed by. They then took a three-day train ride without food or water to reach a prisoner-of-war camp in Poland.

Greasley’s love, Rosa Rauchbach.

Greasley was soon moved to Stalag VIIIB 344, a PoW camp near Lamsdorf, Poland, where he and his fellow PoWs worked in a quarry breaking marble for German headstones. It was there where he met Rosa Rauchbach. She was the quarry owner’s daughter, brought in as a translator.

Sparks flew, and after they kissed in one of the empty workrooms, Greasley fell head over heels for her. He began sneaking out of camp to meet her two to three times a week. She also helped his fellow PoWs by bringing food and radio parts for him to smuggle back into camp. The parts allowed them to build a radio and listen to news on the BBC.

Horace Greasley on the right with other PoWs in a camp in Poland.

It’s important to understand that, though some were worse than others, German-run PoW camps were nothing like their concentration camps. Germany had signed the Geneva Convention in 1929 and, for the most part, they abided by the rules of war it lays out, at least with fellow signatories Britain and England.

So while they starved and worked Russian PoWs to death, the Germans allowed British soldiers a fair amount of freedom within the camps. What’s truly uncommon here is the number of times Greasley accomplished this feat.

Stalag VIIB 344, the camp where Greasley met Rauchbach–note the double fencing.

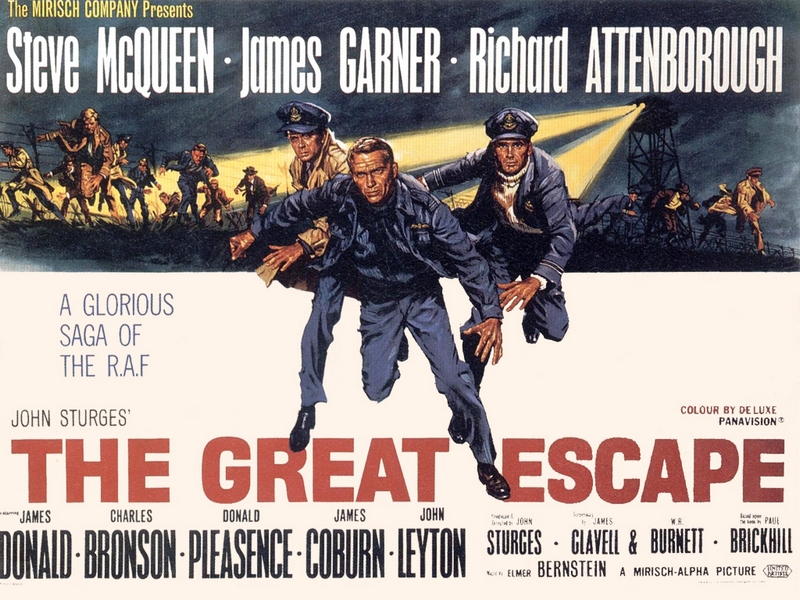

Though they were lax in their patrols, German guards would shoot most who escaped on sight. The Aktion Kugel, or Bullet Action, also known as the Bullet Decree, allowed guards to shoot any non-American and non-British PoWs. The decree was amended to include Britons after the Great Escape on March 25, 1944, which was led by men of the Royal Air Force.

A reconstructed guard tower on display at the Lamsdorf memorial. Source: Memorial Museums

Not only was it not against international law for prisoners of war to escape, it was considered their duty to attempt it in order to return to the front. However, the American and British armed forces relieved PoWs of that duty after 50 of the 80 men involved in the Great Escape were captured and killed by the Germans in April 1944.

So it is fitting that the 1963 movie about the event, The Great Escape, starring Steve McQueen, closes with the words: “This picture is dedicated to the fifty.”

Based on the non-fiction account of the same name by Paul Brickhill. Source: The Real Great Escape

A couple of months into Greasley and Rauchbach’s steamy affair, he was transferred to Freiwaldau, which was an annex to the infamous Auschwitz. Being in a remote location, 40 miles from his previous camp, Freiwaldau’s guards were especially lax. They assumed that any escapee was signing his own death warrant from starvation or exhaustion if he attempted to reach the nearest safe country, Sweden, which was 420 miles away.

Horace Greasley spent two weeks watching their movements and learned exactly when to time his escape. A couple of comrades helped by pushing him out of the window, and he bolted through the fence and into the woods.

Rauchbach had traced him, and they would meet in a chapel two or three times a week. “We’d be up there until two or three in the morning, making love,” Greasley said in an interview a couple of years before his death.

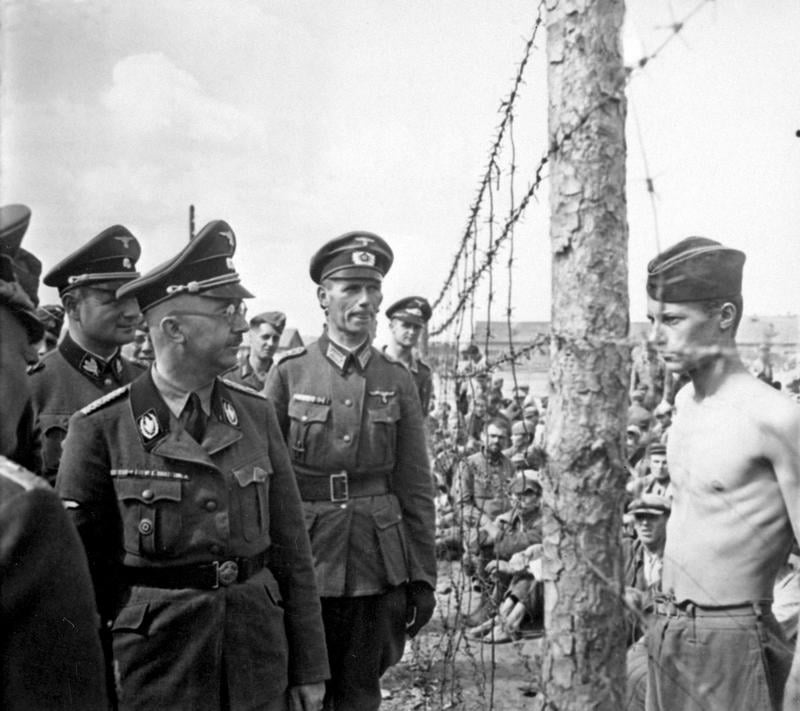

Heinrich Himmler is on the left, wearing glasses; Greasley claimed that he was the PoW on the right.

Greasley isn’t just known as the Houdini of PoWs. He also claimed that this was a picture of him standing up to Heinrich Himmler. He took his shirt off to show his ribs in an effort to prove that he and his comrades weren’t being fed well enough, he said.

Guy Walters, an author, historian, and WWII expert, doesn’t believe it for a minute. He points to the National Archives, having determined that this photo was taken in Minsk, hundreds of miles from Greasley’s camp. What’s more, Walters adds, the PoW in the photo was a Russian soldier. “I would stand up in a court of law and say the proof is absolutely overwhelming,” Walters said. “He certainly didn’t meet Himmler.”

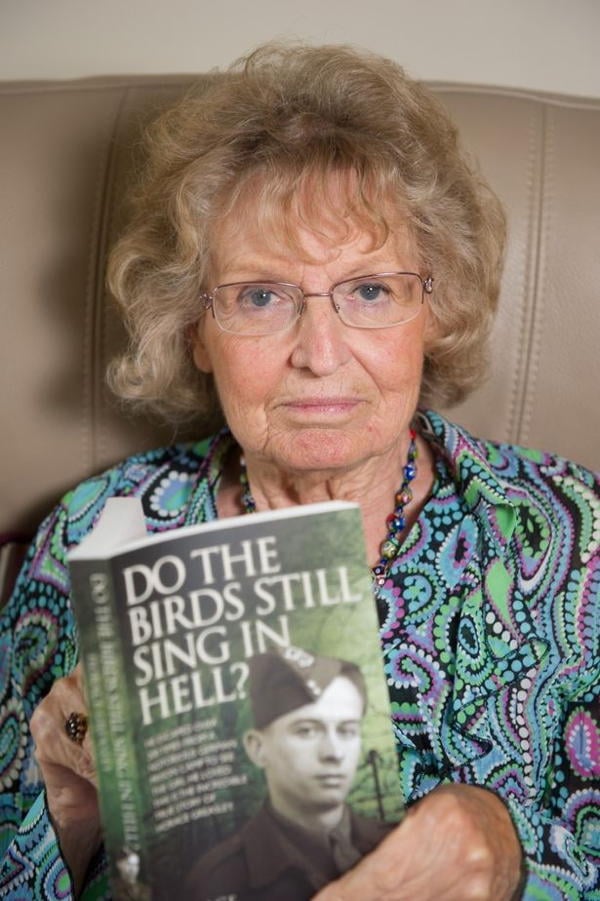

Brenda Greasley. Source: The Birmingham Mail

Horace Greasley’s wife, Brenda–they met in 1970 and married in 1975–is outraged at Walters’ comments.

She wrote a fiery letter to the Daily Mail after the paper printed a Walters article about Greasley and other memoirists of WWII. “As Horace Greasley’s widow, I find his inclusion among “Holocaust fantasists” (Mail) objectionable. He’s being labelled a liar and a memory-failed old man. In fact, he had an excellent memory and his mind was as keen as a knife.” She adds that she wants to “meet this supposed historian Guy Walters face to face and we’ll see who’s telling the truth.”

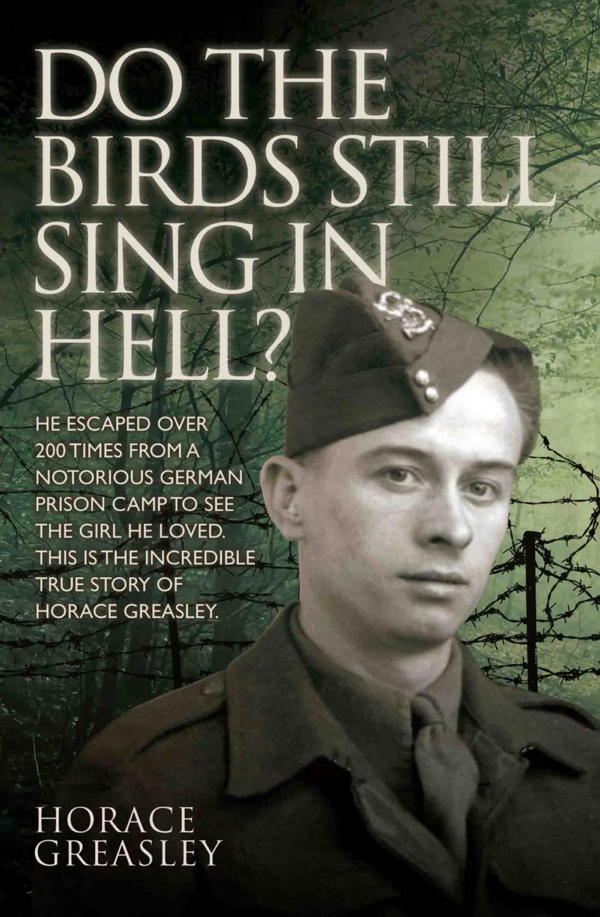

Horace Greasley’s memoir, which was ghostwritten by Ken Scott.

Greasley’s war experiences are apparently going to be made into a film. Names rumored to be attached to the project include director Ron Howard and actors Robert Pattinson and Alex Pettyfer, who are being considered to play Greasley, but no final decisions have been announced.

One possible option to play Horace “Jim” Greasley: Alex Pettyfer Source: Wallpapers HD Download

The most recent article on the subject claims that Stratton Leopold, executive producer of movies like Mission Impossible III and The Sum of All Fears, is working on the film with Silverline Productions. Ken Scott, the ghostwriter of Greasley’s book, says, “I can say it will be a mix of German and British actors and they are A-listers.”

At present, locations for filming are said to include Poland, Pinewood Studios in the UK, and Los Angeles.

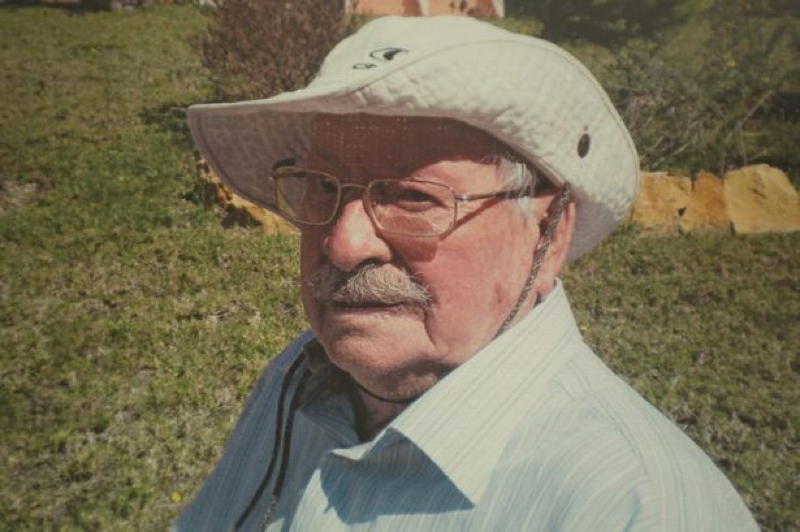

Greasley in his late 80s Source: The Birmingham Mail

After his PoW camp was liberated and he returned to England, Greasley and Rauchbach exchanged several letters until one day, hers stopped coming. Then he received a letter from a friend of Rauchbach’s, informing him that Rosa died in childbirth along with the baby. He never learned if the child was his.