On September 6, 1949, Howard Unruh killed 13 people in 12 minutes. If he'd had enough bullets, he later said, he would have "killed a thousand."

In recent decades, the United States has become a world leader in gun violence — particularly mass shootings. Sadly, it seems like every few months that one troubled person will take out their anger or hatred on a large group of people and do so with a gun.

But when did this begin? Murder has been a part of the human experience since the beginning, and gun violence is nothing new, but when exactly did this large-scale practice of “mass shootings” begin, at least in the U.S.?

While there may be no easy answer, some believe it all started with a man named Howard Unruh. On September 6, 1949, Howard Unruh walked through his hometown of Camden, N.J. and fatally shot 13 people in just 12 minutes. It quickly became known as the “Walk of Death,” and it may also very well be the first mass shooting in American history.

The Troubled Life Of Howard Unruh

Many experts believe Howard Unruh — born in Camden on Jan. 21, 1921 — had always shown signs of being disturbed, all the way back to his early childhood. A psychiatric evaluation performed after the shooting showed he’d had a “rather prolonged” period of toilet training as a child, and hadn’t walked or talked until he was 16 months old. At the time, his late-blooming didn’t strike anyone as being odd, though post-arrest evaluations seized on these details.

But aside from his delayed maturity, Howard Unruh hadn’t displayed any significantly unusual behaviors. His parents separated when he was young, and he and his younger brother James were raised by their mother Freda afterward. His school records showed that he was shy and had ambitions to work for the government.

After high school, Unruh joined the Army and was deployed to serve in the European Theater of World War II. Certain incidents from his time there would likewise later be looked back upon as signs of his being disturbed.

While his commanders reported that Howard Unruh was a competent soldier and a good marksman, it was his personal behavior that worried others. While in combat, Unruh kept a diary in which he recorded every German soldier he killed. He would note the time, date, and circumstance, and describe the aftermath (and the body) in incredible, gory detail.

James would later recall that after returning from the war, his brother was never the same. Indeed, after coming home in 1945, Howard Unruh spent four miserable years living with his mother in Camden, slowly turning into an even more disturbed and psychotic young man.

During the four years between leaving the Army in 1945 and his “Walk of Death” in 1949, Howard Unruh spent his time keeping track of every perceived personal affront made against him — and thinking up ways to make the offenders pay.

Two persistent sources of perceived affronts were neighbors Maurice and Rose Cohen, who owned the pharmacy below Unruh’s home and whose backyard abutted his. They’d squabbled over a gate he’d put up between their yards, Rose had yelled at Unruh about the volume of his music, and Maurice had reportedly called the indeed homosexual Unruh a “queer.”

For this, and plenty of other affronts both real and imagined, Howard Unruh was about to get his revenge.

The Walk Of Death

Ralph Morse/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty ImagesMrs. James W. Hutton, who lost her husband when he was standing in a doorway as Howard Unruh came in and shot him.

On the evening of Sept. 5, 1949, Howard Unruh put himself to sleep the same way he had every night for the past four years: by running through the laundry list of people – mostly his neighbors – who he felt had offended him, and all of the ways he could make them pay.

He was particularly angry that night because when he’d arrived home, he’d noticed that the garden gate he’d recently installed between his yard and the Cohen’s had been broken. For Unruh, who had slowly been becoming unhinged, this was the final straw. Tomorrow, he would do what he’d been dreaming of for years – get revenge on all those who had upset him.

The next morning, Sept. 6, Unruh awoke to breakfast being prepared by his mother, as usual. And, as usual, the two squabbled over a small matter. However, this particular squabble appeared to have escalated, as Unruh’s mother stormed out of the home she shared with her son and left for a neighbor’s house at around 9:10.

Ten minutes later, Howard Unruh emerged from the house armed with a German Luger P08, a 9mm pistol he’d purchased in Philadelphia for less than $40.

First on his kill list was a local shoemaker named John Pilarchik, who he shot and killed instantly. Next, Unruh walked over to the local barbershop, where proprietor Clark Hoover was cutting the hair of a six-year-old boy named Orris Smith, who sat atop an old carousel horse as Hoover worked while the boy’s mother sat nearby. Unruh shot the boy first, then Hoover. He ignored the mother.

Back on the street, Unruh shot seemingly aimlessly at a boy in a window, who managed to avoid the shot. Then, Unruh turned his attention to a tavern across the street, into which he fired multiple shots though he himself didn’t actually go inside. Witnesses would later recall Unruh walking carelessly through the street, almost meandering, with a stoic look on his face as he fired shots into the bar. Shockingly, no one in the tavern was hurt.

Ralph Morse/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty ImagesMr. and Mrs. Joseph Hamilton, who lost their two-year-old son, Tommy, when Howard Unruh saw him through a window and fired two fatal shots.

After the tavern, Howard Unruh headed to the local drugstore, the workplace of perhaps his most sought-after targets, Maurice Cohen and his wife, Rose. While he was on his way to the drugstore, a bystander accidentally walked into Unruh. Unruh shot him without a second thought.

The Cohens saw Unruh coming but weren’t quick enough. Cohen’s wife, Rose, who had been hiding in a closet, was shot several times. Cohen’s mother, Minnie, who had been attempting to call the police, was also shot. Finally, Unruh shot Maurice, who had attempted to escape onto the roof. The shot propelled Maurice off the roof and onto the pavement below.

Still, though, Howard Unruh wasn’t finished. He shot a passerby in a car who had slowed down at the sight of Cohen’s body on the street. He then turned around and shot at another car, killing the driver and one of the two passengers.

Finally, he made his way to the tailor shop in search of his final two victims. Unfortunately, the tailor wasn’t home, so Unruh settled for shooting his wife. Then, in what he would admit was his only mistake that day, Unruh shot at what he thought was a shadow but turned out to be a two-year-old child playing with a toy.

By the end of the Walk of Death — a mere 12 minutes from start to finish — Howard Unruh had killed 12 people and injured four. One of the injured would later die from his wounds, bringing the death toll of what may have been American history’s first mass shooting to 13.

Howard Unruh’s Last Stand

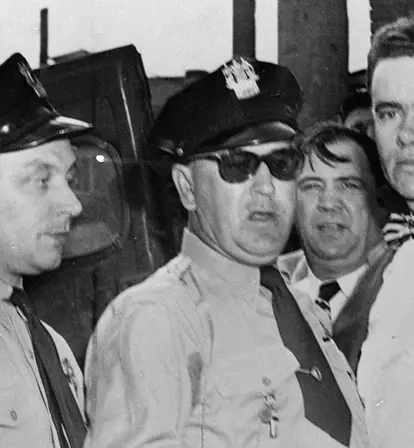

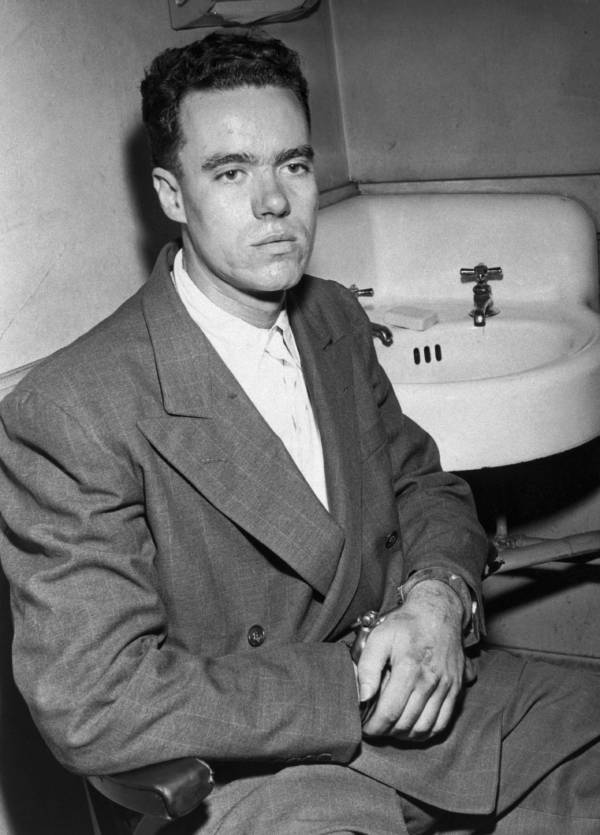

Bettmann/Contributor/Getty ImagesHoward Unruh, his hands shackled, sits in Camden City Hall after undergoing questioning by detectives following his “Walk of Death.”

Following the unintentional killing of the two-year-old child and knowing police had been alerted and were on their way, Howard Unruh ran back to his home and barricaded himself in.

By then, the police had surrounded the area and were intent on bringing Unruh in alive. At the time, there was little police protocol in place for such an incident. Should they enter the home? Should they wait for him to come out? Should they simply open fire?

Across town, while the police plotted their next move, local newspaper editor Philip Buxton, who had heard of the commotion, got an idea. Looking up Unruh’s phone number in the phonebook, he simply called the man. And to his surprise, Howard Unruh answered. Buxton recorded the transcription of the call:

“Is this Howard?”

“Yes … what’s the last name of the party you want?”

“Unruh.”

(Pause) “What’s the last name of the party you want?”

“Unruh. I’m a friend, and I want to know what they’re doing to you.”

“They’re not doing a damned thing to me, but I’m doing plenty to them.”

(In a soothing, reassuring voice) “How many have you killed?”

“I don’t know yet, because I haven’t counted them … (pause) but it looks like a pretty good score.”

“Why are you killing people?”

“I don’t know. I can’t answer that yet, I’m too busy.”

[At this point, Buxton heard gunfire in or near the Unruh home]

“I’ll have to talk to you later … a couple of friends are coming to get me” … (voice trails off).

It was then that police decided what to do. Crawling up to the roof, police dropped teargas into Unruh’s home through a window. Shortly after, he expressed his intent to surrender. As he walked out, the police patted him down and cuffed him. One asked him just what he’d been thinking.

“What’s the matter with you?” he demanded. “You a psycho?”

“I am no psycho,” Howard Unruh replied. “I have a good mind.”

Life Behind Bars

A police investigation followed Howard Unruh’s arrest, though it was hardly necessary. He confessed immediately and took full responsibility for the shootings. He gave the police a detailed description of what had happened, and police noted the same careless, stoic attitude witnesses had reported seeing in Unruh as he shot up the tavern.

At that point during the interview just after the arrest, one of the police officers noticed blood pooling on the floor under Unruh’s chair. Sometime during the day – Unruh wasn’t quite sure when – he’d been shot in the leg. He was taken to the hospital, though the bullet couldn’t be recovered. Instead, he was patched up and shipped off to the psychiatric unit at Trenton Psychiatric Hospital.

Over the course of his stay, dozens of psychiatrists attempted to figure out what drove him to kill, though none were entirely successful. The farthest they got was getting Unruh to admit that what he’d done was wrong.

“Murder’s a sin,” he told them. “And I should get the chair.”

But, alas, Unruh would never truly answer for that sin. In 2009, Howard Unruh died in the Trenton Psychiatric Hospital — his last words were reportedly “I’d have killed a thousand if I had enough bullets” — never having stood trial for what may have been the first modern mass shooting in American history.

After this look at Howard Unruh, read about the world’s largest mass suicide, the Jonestown Massacre. Then, read about Olga Hepnarova, a truck-driving mass murderess.