When he took the podium to deliver the "I Have A Dream" speech in Washington, D.C. on August 28, 1963, Martin Luther King wasn't even going to utter that immortal line — then fate interceded.

On August 27, 1963 — the night before one of U.S. history’s most momentous demonstrations — Martin Luther King Jr. and his colleagues set up shop in Washington, D.C.’s Willard Hotel, where they made some final preparations for King’s “I Have a Dream” speech that was to be delivered the next day.

“Don’t use the lines about ‘I have a dream’,” adviser Wyatt Walker told King, according to The Guardian. “It’s trite, it’s cliche. You’ve used it too many times already.”

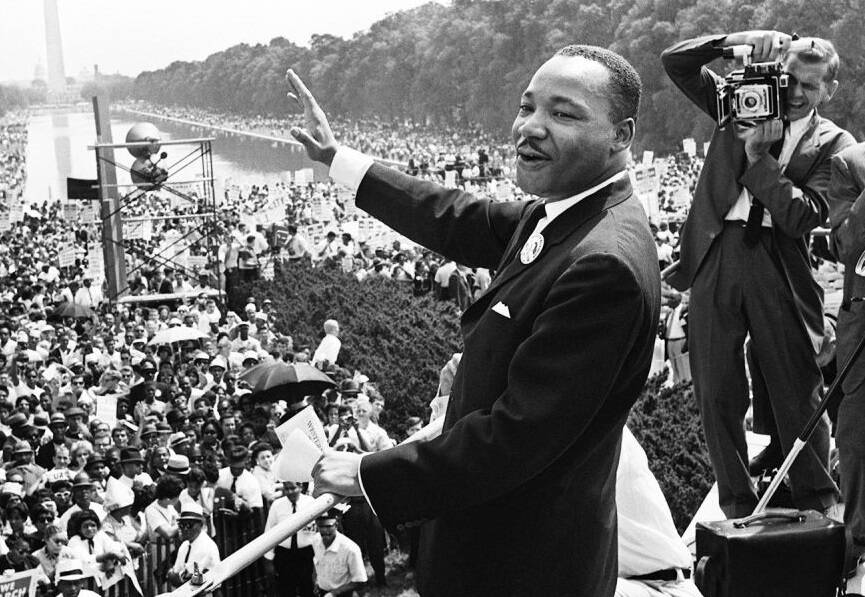

AFP/Getty ImagesMartin Luther King Jr. waves to supporters from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial on August 28, 1963 upon delivering his iconic “I Have a Dream” speech.

King had indeed used the line before: once at a Detroit rally and again at a Chicago fundraiser. This speech, to be broadcast on all three television networks and thus a much wider audience, had to be different, his advisers said.

“I am happy to join with you today in what will go down in history as the greatest demonstration for freedom in the history of our nation.”

To King’s advisers, not going with the “I have a dream” rhetoric also made sense given the March on Washington’s schedule. Originally, planners allotted the speakers five minutes each, with King speaking in the middle for that same length of time. One of King’s advisers, attorney and speechwriter Clarence Jones, pushed for an alternative arrangement the night before — unwittingly helping to set the stage for a historical speech by giving King more time with which he could tell people about his dream.

“I said you run the risk…that after he speaks a lot of the people at the march will get up and leave,” Jones told WTOP.

National ArchivesMartin Luther King Jr. giving his famous “I Have a Dream” speech in Washington, D.C. 1963.

Instead, Jones recommended that King speak at the end of the event — and for the longest amount of time. After an evening of constant back and forth, King agreed. Before he retired to his bedroom, Jones handed King the speech for his review.

“One hundred years [after the Emancipation Proclamation] the life of the Negro is still badly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination. One hundred years later the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity.”

It was, Jones later recounted, “a summary of what we had discussed before” that he had “simply put…into textual form in case he wanted to use that to reference in putting his speech together.”

Document in hand, King bade his colleagues adieu. “I am now going upstairs to my room to counsel with my Lord,” King said. “I will see you all tomorrow.”

At 4 a.m., the story goes that King gave the text of what would become the “I Have a Dream” speech to his aides for print and distribution. Apparently abiding by Walker’s recommendation, the “I have a dream” line did not appear in the text at all.

King rose to fame as a spiritual leader and unifier of black Americans in the 1950s. His role as president in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, as well as leading organized protests, established him as a reliable leader.

Fighting For The Dream

Before King could deliver a speech like “I Have a Dream” at an event as historic as the March on Washington, he and his followers had endured a long road filled with struggle.

Many of the civil rights campaigns organized by King or his compatriots in the preceding years, like the 1961 Freedom Rides or the 1963 Birmingham Campaign, saw participants viciously beaten. But their struggle was beginning to garner more and more attention and support.

The Freedom Rides, for example, led the Interstate Commerce Commission to rule that segregation on buses and in stations was no longer legal. Meanwhile, televised reports on the Birmingham Campaign allowed otherwise shielded Americans to witness just how brutal the struggle for civil rights was.

“There are those who are asking the devotees of civil rights, ‘When will you be satisfied?’ We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of unspeakable horrors of police brutality.”

It was during this same period, one in which King wrote his famous “Letter from Birmingham Jail” during the campaign in that city, that he decided to begin working toward another high-profile event that would aid his cause.

With help from Bayard Rustin, a veteran of organizing large-scale events such as this, the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom was prepared by summer 1963.

The goals were simple and concise: desegregated public schools and accommodations, a redress of constitutional rights violations, and an expansion of the federal works program that would train novice employees.

“We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation. So we’ve come to cash this check, a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice.”

When the day finally came — and artists such as Bob Dylan and Joan Baez united the crowds in cheerful celebration — nobody could’ve anticipated just how many people would actually show up in solidarity.

The Inside Story Of The “I Have A Dream” Speech

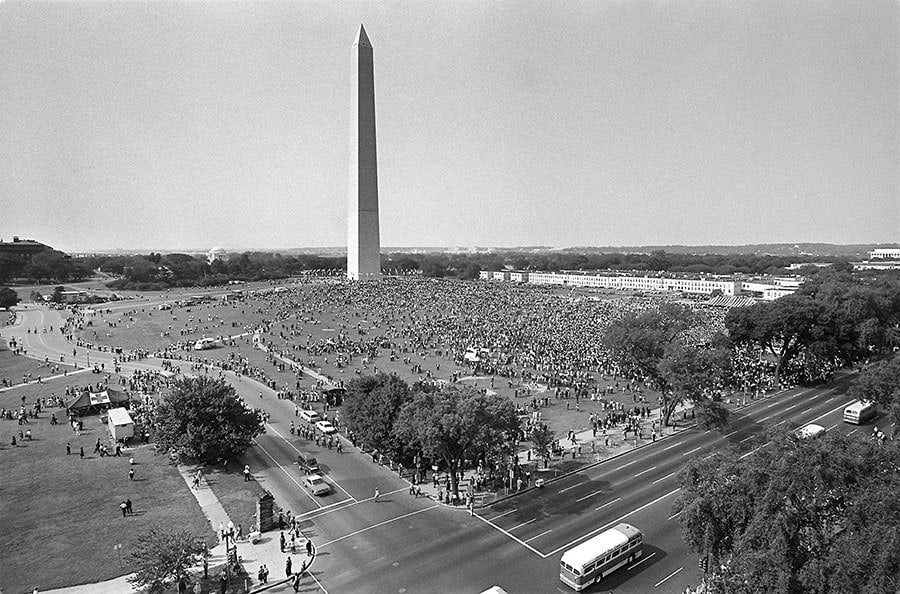

AFP/Getty ImagesMore than 200,000 civil rights supporters gather at the National Mall in Washington, D.C. on August 28, 1963.

The March on Washington defied all expectations. Organizers planned for 100,000 people to occupy the National Mall that day; instead, around 250,000 people showed up to demand civil and economic rights. King appeared 16th on the official program — just before the benediction and pledge.

“This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism. Now is the time to make real the promise of democracy.”

When King’s time came to speak, he approached the podium with one critical figure behind him: singer and activist Mahalia Jackson. According to Jones, King considered her the “Queen of Gospel” because she was someone whom he would turn to when things got rough. “When Martin would get low…he would track Mahalia down, wherever she was, and call her on the phone,” Jones wrote in Behind the Dream, a book about the speech.

As King spoke, he initially kept very close to the script. About midway through, King paused and looked out toward the crowd. That’s when Jackson — there to sing before and after King’s address — cried out to King, “Tell them about the dream, Martin. Tell them about the dream.”

Wikimedia CommonsMahalia Jackson performing in 1957.

King responded almost reflexively to Jackson — some said his physical posture changed after Jackson’s call — and to those who understood their relationship, this wasn’t exactly surprising. It was “one of the world’s greatest gospel singers shouting out to one of the world’s greatest Baptist preachers,” Jones told the New Orleans Times-Picayune. “Anybody else who would yell at him, he probably would’ve ignored it. He didn’t ignore Mahalia Jackson.”

“This sweltering summer of the Negro’s legitimate discontent will not pass until there is an invigorating autumn of freedom and equality — 1963 is not an end but a beginning.”

Indeed, video footage shows King push his notes aside and opt for a more free-flowing style not unlike his sermonizing. “I turned to somebody standing next to me and I said, ‘These people don’t know it, but they’re about to go to church’,” Jones said.

After an extended pause punctuated by Jackson’s call, King would make history on the spot and deliver the “I Have a Dream speech” as we know it today. “So even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow,” King said extemporaneously, “I still have a dream.”

The Enduring Legacy Of King’s “I Have A Dream” Speech

While King had used such language in speeches before, he had never uttered the words “I have a dream” in front of such a large audience before. In fact, he had never spoken in front of this kind of audience before.

“The overwhelming majority of people in America, white people particularly, had never heard or seen Martin Luther King Jr. speak before,” Jones said.

“You had television pictures and the voice of Martin Luther King rebroadcast as part of the evening news in the top 100 television markets in the country. So, when the nation saw and heard this person speaking, they had as delayed reaction as I had when [the speech] was given. I was mesmerized.”

Not everyone was as mesmerized as Jones, however. While president John F. Kennedy remarked, “He’s damned good, damned good,” others thought the speech fell a bit flat.

“We must forever conduct our struggle on the high plane of dignity and discipline. We must not allow our creative protests to degenerate into physical violence.”

“I thought it was a good speech,” civil rights activist John Lewis, who addressed the march earlier that day, said. “But it was not nearly as powerful as many I had heard him make. As he moved towards his final words, it seemed that he, too, could sense that he was falling short. He hadn’t locked into that power he so often found.”

Wikimedia CommonsExpectations for attendance were set at 100,000 people, but more than twice that showed up to voice their support.

Nor did much of the nation really “lock in” to the power of King’s message. In the years that followed his speech and culminated in his 1968 assassination, King suffered a number of setbacks. Though historic triumphs like the Civil Rights Acts of 1964 and 1968 lay ahead, King faced increasing criticism for positions like opposition to the Vietnam War.

For many, right or wrong, the “I Have a Dream” speech remains the high-water mark of King’s career. That said, it wasn’t instantly regarded as historic in the way that we might think today.

“There was no reason to believe that King’s speech would one day come to be seen as a defining moment for his career and for the civil rights movement as a whole,” said The Dream author Drew Hansen.

“I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will be not judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.”

In fact, as historians note, it wasn’t until King’s April 1968 assassination that the public “rediscovered” the speech, which became “one of those things that we look to when we want to know what America means,” Hansen said.

And to think, had it not been for an assertive speechwriter and the sudden cry of a gospel singer, Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” might have never have even come to fruition at all.

Next, discover ten fascinating things you never knew about Martin Luther King Jr. Then, read all about the death of Martin Luther King Jr.