Standardization and Human Rights Violations

Wikimedia Commons

The 1790 Immigration Act mostly (but not completely) dissolved state control over immigration and reserved powers over admission to the federal government. For the first time, the United States had a unified policy, albeit one that trod very lightly on states’ rights.

The Act set a uniform residency requirement of two continuous years for immigrants hoping to be naturalized. Under this system, immigrants would have to prove – to their state officials, not the federal government – that they had legally resided inside the state and had demonstrated good conduct in order to qualify for naturalization.

Within that loose framework, each state was at liberty to impose secondary requirements and procedures. In all, the approach was similar to modern laws on gun control: Some states were very strict, while others barely regulated the practice, but all states were bound by limited federal laws.

Shortly after the ink dried on the first Immigration Act, powerful members of the Federalist Party started agitating for greater control on a federal level. Citing fears of Irish Catholics and French revolutionaries flooding into the country, they pushed for the right to arbitrarily detain and deport foreign-born troublemakers.

In 1798, President John Adams granted their wish with the Alien and Sedition Acts. These laws gave the government the power to arrest foreigners who were perceived to oppose the ruling Federalist Party line, and to deport them at will.

The Democratic-Republican faction, led by Thomas Jefferson, was aghast at this, if only because its members saw those foreign anarchists as perfectly good potential voters. When Jefferson assumed the Presidency, the 1798 Acts were quietly disregarded and then repealed. America’s first great immigration panic was over.

Direct Federal Control and National Policy

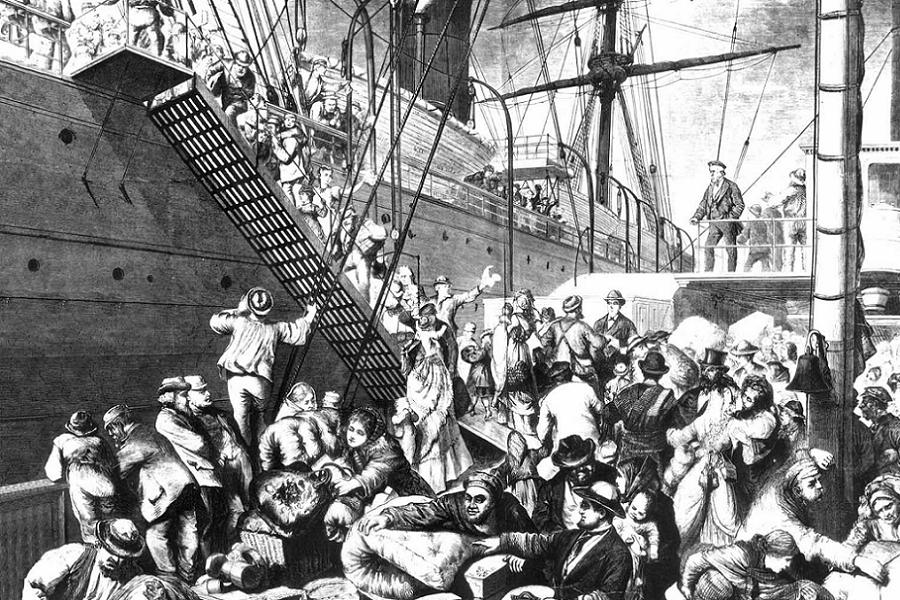

Wikimedia CommonsGerman immigrants fled their homeland by tens of thousands in the early and mid-19th century. In this woodcut, a German family waits with their baggage on the dock.

Immigration law got its first major overhaul under President James Monroe in 1819, as refugees from the Napoleonic Wars and reactionary restorations fled across the Atlantic. Unlike the situation in 1790, the United States now had vast land claims in the West to settle, and it had recently taken over Spanish and French claims to Florida and the Louisiana Territory, respectively.

These lands were mostly under federal authority, not yet having been organized into new states themselves, and they were mostly empty of European settlers. If the United States wanted to assert long-term control over these possessions, it would have to fill them up with its own people as quickly as possible.

These two factors — direct federal control of most of the land in the country and a crying need for settlement — motivated Congress to act in 1819 and centralize immigration policy for the whole country, as well as to gently push the new arrivals out into Indian lands, where presumably one problem could solve another.

The 1819 Act required states to report on immigration numbers, and it also set rules for food, water, shelter, and other provisions for emigrants on US-bound ships that were authorized to carry them across the Atlantic.

No quotas or targets were set by this Act, but the presumption was that virtually everybody admitted would be from friendly European countries.

In 1864, facing a major labor shortage during the Civil War, Congress would act again to hire and import foreign-born contract laborers. This was essentially a guest worker program, and it was wildly unpopular among unemployed Irish immigrants in the North, who were already fighting with free black labor over every job they could get.

The Act also centralized control over immigration policy with the State Department, where a special commissioner was assigned to oversee policy. The controversial contract laborer program was quietly canceled in 1885.