The Iroquois Theater Fire is considered one of the worst building disasters in U.S. history and played a huge role in changing building safety standards.

Chicago History MuseumThe Iroquois theater fire started on the stage and left it charred.

On Dec. 30, 1903, almost 2,000 people crammed into the Iroquois Theater in Chicago to watch a matinee performance of “Mr. Bluebeard.” But shortly after the second act began, a spark from a stage light caught a curtain on fire. And a blaze soon began to spread.

Though the theater (also called Iroquois Theatre) had opened just five weeks earlier and was billed as “fireproof,” the fire spread from the stage into the audience. And as the panicked crowd rushed to the exits, they created a deadly stampede. Many people were trampled to death, while those who managed to reach the exit doors found that some of them were locked.

Some 600 people ultimately lost their lives in the blaze, and the Iroquois Theater fire was considered the worst building disaster in American history — until September 11, 2001.

How The Iroquois Theater Disaster Began

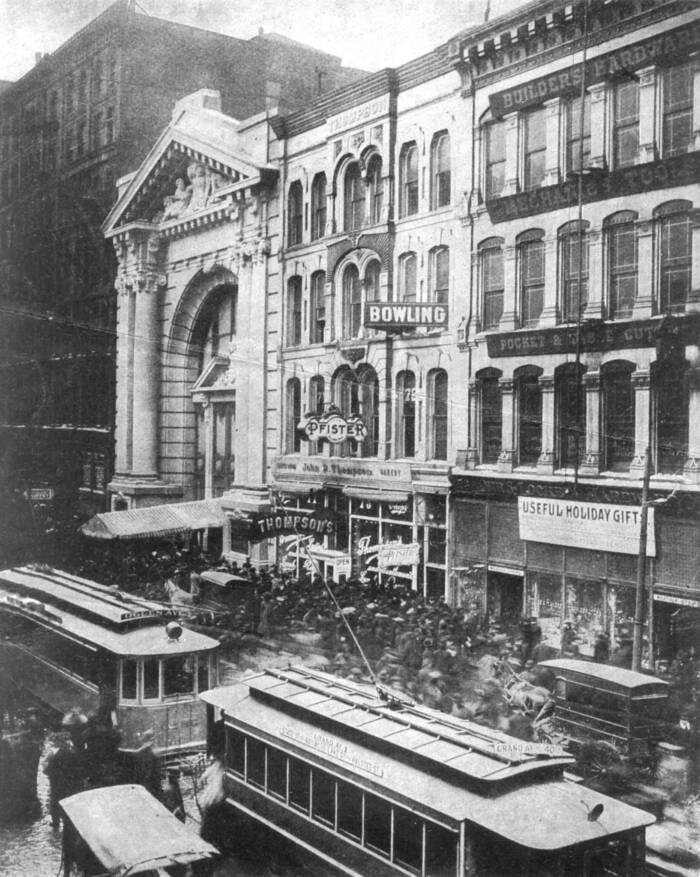

Chicago History MuseumThe Iroquois Theater opened just five weeks before the fire.

The Iroquois Theater fire began around 3:15 p.m. on Dec. 30, 1903. The theater was full that day, as 1,700 audience members — plus 250 standing room — had come to see a performance of the musical comedy “Mr. Bluebeard.” Many of the people in the audience were children.

The play’s second act had just begun when a spark from a stage light caught a curtain on fire. Neither a stage hand nor the theater’s fireman could extinguish the fire, according to The Iroquois Theatre Fire Historical Society, and the blaze swiftly began to spread.

Actor Eddie Foy was waiting for his cue when the blaze broke out. As he later testified during a coroner’s inquest, he was in his dressing room when he started to smell smoke.

“The Moonlight Ballet was on and it was three minutes before the time of my entrance,” Foy testified. “I looked up and immediately over me, in the left first entrance, I saw sparks and a small cloud of smoke.”

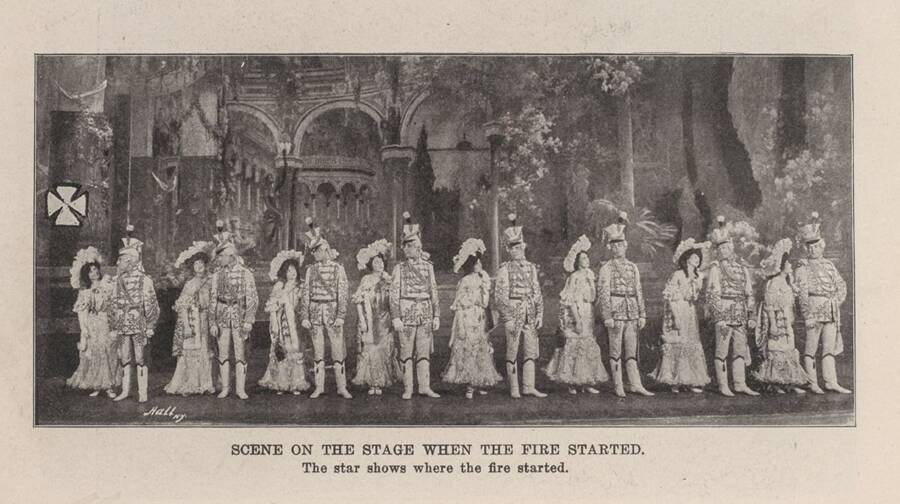

Chicago History MuseumA scene from “Mr. Bluebeard” at the Iroquois Theater.

Foy leaped into action. He rushed on stage and tried to prevent the audience from panicking by reassuring them that everything was under control. But while Foy’s words may have calmed people in the main part of the theater — many of whom were not crushed in the subsequent stampede and survived the fire — it did little to calm the rest of the audience.

Indeed, it was clear by that point that everyone was in severe danger. Burning debris fell around Foy as he spoke, and when cast members opened a rear theater door to escape, the backdraft created an enormous burning fireball which exploded inside.

Foy witnessed a “mad, animal-like stampede,” as he later wrote in his memoir. As the audience surged toward the exits, “their screams, groans and snarls, the scuffle of thousands of feet and bodies grinding against bodies merging into a crescendo half-wail, half-roar.”

But those who managed to reach the exits found that many of them were locked.

The Desperate Escape From The Iroquois Theater

Though there were dozens of exits in the theater, many of them were locked. What’s more, audience members in the balcony found themselves trapped by metal gates meant to keep them from sneaking to “better” seats during intermission, and some of the upper-level fire escapes lacked ladders that reached to the ground. Even the skylights on the roof were fastened shut.

Chicago History MuseumA fireball ripped through the theater, killing many instantly.

Meanwhile, even audience members that found unlocked doors found themselves in peril. Some of the doors opened inward, or with a device that most people were unfamiliar with, which resulted in a terrible crush near the exits as people pushed, shoved, and climbed over each other in their desperate bid to escape. In the upper sections of the Iroquois Theater, people jumped to their death to avoid being burned alive.

Maud A. MacDonald Nickey, who attended the theater solo that day, was in the 10th row of the orchestra when the Iroquois Theater fire began. Running first to the rear of the theater, then toward the stage, Nickey eventually followed the sound of breaking glass and found a man forcing open a window. Though the drop to the pavement was short, the crush was so intense that people cascaded on top of each other. Nickey later testified that she was almost killed by someone who landed on her after she escaped.

Eleven-year-old Elson Barnes, meanwhile, managed to survive because she was seated next to a side stairway.

“[T]here was a stampede and people were on top of each other six feet deep,” Barnes wrote to her parents the day she escaped the fire. “[T]he mob pushed me down and there were three people on top of me. I cried out and a man jerked me by the arms and pulled me out.”

Public DomainSome escaped the upper levels by crawling to the third floor of a nearby building. But the first two who tried to cross the planks fell to their deaths.

But many people were not as lucky. Ultimately, some 600 people perished in the Iroquois Theater fire and 250 were injured.

Why The Iroquois Fire Was So Deadly

The Iroquois Theater Fire lasted just 15 minutes. But by the time firefighters arrived, hundreds of people had already died.

As Foy wrote: “When a fire chief thrust his head through a side exit and shouted, ‘Is anybody alive in here?’ not a sound was heard in reply.”

Chicago History MuseumChicago firefighters attempted to put out the blaze.

With its high death toll, the Iroquois Theater fire became the worst single building disaster in American history, until the September 11 attacks almost 100 years later. So why was the blaze so deadly?

The problems started with the design of the theater. Architect Benjamin Marshall wanted a grand, sweeping staircase — the theater’s only entrance — which created a crushing mob during the evacuation. And while the theater had some 30 exit doors, none of them were marked with lights because the theater owners didn’t want the lights to distract the audience.

Meanwhile, many exit doors were locked to keep people from sneaking into the theater, the fire escapes on the upper levels hadn’t been completed, and theater didn’t have a functioning fire alarm or sprinklers. To make matters worse, the fire extinguishers in the theater didn’t work.

Library of CongressA panoramic photograph of the theater’s interior showed the devastation that took place in just 15 minutes.

But the theater’s owners blamed the audience for the tragedy, stating that the Iroquois Theater fire was so deadly because people had panicked despite being “admonished… to be calm and avoid any rush.” Marshall echoed them, claiming that there were enough exits in the building to avert disaster but that people had become “panic stricken and stunned.”

In the end, a grand jury indicted the owner, business manager, and stage carpenter for manslaughter. But the criminal cases ultimately fizzled out with zero convictions.

Chicago History MuseumCrowds gathered outside the Iroquois Theater, hoping for news of survivors.

That said, the Iroquois Theater fire did have a huge impact. Within weeks, building regulations were updated across the country to prevent such a disaster from happening again. The new laws required red lights over all exit signs, occupancy limits, and panic bars on emergency exits that made them easier to open.

“The only atonement that can be made to these hapless victims of negligence is to make the theaters of Chicago absolutely safe, so that none others may meet their fate,” declared the Chicago Tribune.

Tragically, for the hundreds of men, women, and children who perished in the Iroquois Theater fire, these changes came far too late.

Disasters like the Iroquois Theater fire were sadly common in the early 20th century. Next, read about the tragic Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, and then learn about the Hindenburg disaster.