The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire was the deadliest workplace tragedy in the history of New York City until the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 — but it was completely preventable.

Public DomainFirefighters work to put out the fire overtaking the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in Lower Manhattan.

On March 25, 1911, the tragic Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire broke out at the Asch Building in New York City. Roughly 500 garment workers were packed into the building’s eighth, ninth, and 10th floors when the fire started in a rag bin on the eighth story.

The flames spread quickly among the clothing scraps and wooden baskets, causing a massive panic. Many workers attempted to flee via the building’s elevators, fire escape, and stairs, but locked doors and other safety hazards led to the tragic deaths of 146 men and women.

The factory’s owners, Max Blanck and Isaac Harris, eventually went on trial for their role in the tragedy, but they were ultimately acquitted. Still, workers’ unions rallied to protest the unjust conditions that led to the events, leading to legislation that would change labor laws forever.

The History Of The Asch Building And The Triangle Waist Company

In 1901, the Asch Building was completed in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of Lower Manhattan. Its architect, John Woolley, designed the 10-story building to have two enclosed staircases, a deviation from the standard three staircase requirement for structures of a similar size.

The building's owner, Joseph J. Asch, boasted of its superior design, and he even claimed that it was "fireproof," according to the National Fire Protection Association. This assertion caught the attention of Max Blanck and Isaac Harris, two entrepreneurs who operated a burgeoning garment business.

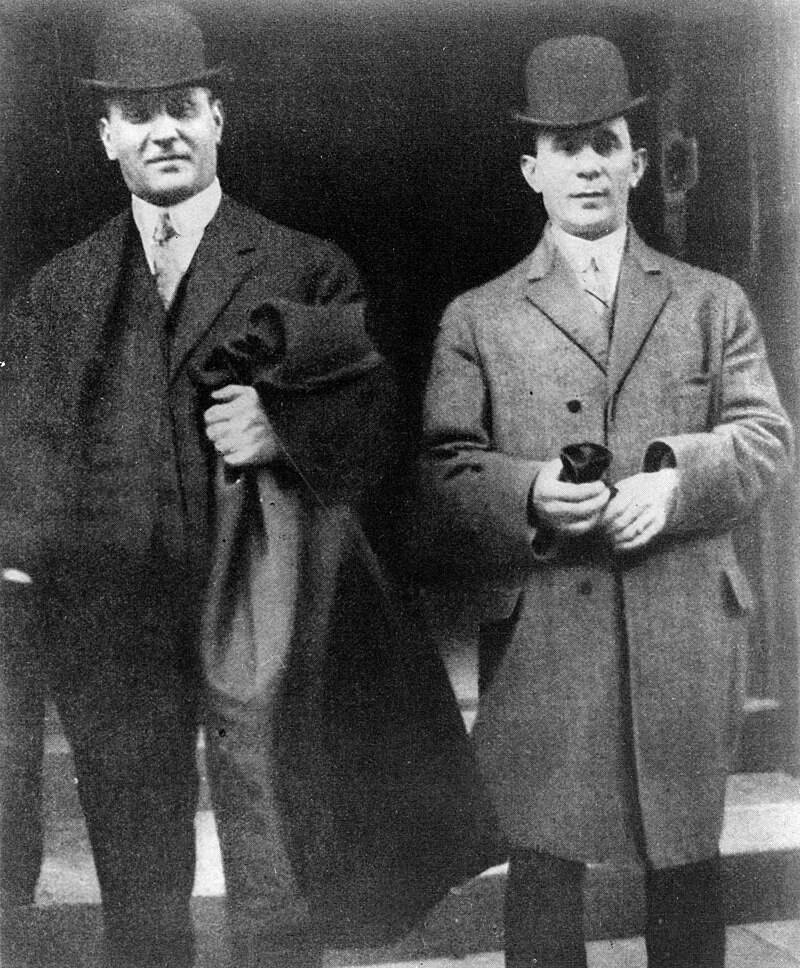

Kheel Center/Cornell University LibraryMax Blanck and Isaac Harris, the owners of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory.

Blanck and Harris had both immigrated to the United States from Russia in the late 1800s. The duo met in New York City in their 20s and bonded over their shared desire to strike it rich. Harris had garment-making experience, while Blanck possessed the business brains that were necessary to operate a successful company.

In 1900, the men formed the Triangle Waist Company and opened their first shop selling shirtwaists, the newest design in women's fashion that allowed for greater mobility and breathability.

By 1902, business was successful enough for Blanck and Harris to rent a space in the Asch Building. There, Harris designed the layout of the factory for maximum productivity. Business continued to boom, and by 1908, the factory had expanded to the top three floors of the building.

Just three years later, the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire would destroy everything inside.

Garment Worker Strikes And The Build Up To The Tragedy

In 1911, the Triangle Waist Company employed between 500 and 600 garment workers, most of whom were young immigrant women of Jewish and Italian descent. They worked long hours — often 12 hours a day, seven days a week — for low wages (about $200 to $400 per week in today's currency).

In the years leading up to the fire, around 20,000 garment workers in New York City, including employees of the Triangle Waist Company, went on strike to protest these long hours and poor working conditions. According to the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO), they demanded a 52-hour work week, overtime pay, and higher safety standards, including unlocked factory doors and functioning fire escapes.

Library of CongressGarment industry employees protesting for better working conditions in what became known as the "Uprising of 20,000."

While some garment companies agreed to these stipulations, Blanck and Harris stood firm. They refused to budge or recognize the unions that formed, and as time went on, things went back to normal at their factory.

Then, in March 1911, almost exactly a year after the strike came to an end, the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire broke out.

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire Claims 146 Lives

Around 4:40 p.m. on March 25, 1911, a fire broke out on the eighth floor of the Asch Building. It likely started due to a cigarette tossed into a rag bin.

Firefighters arrived on the scene within minutes, but the flames were spreading quickly. Many workers on the eighth floor were able to escape down a staircase. Blanck and Harris, whose offices were on the 10th floor, were alerted to the fire by a phone call and climbed through a window onto a neighboring rooftop. However, by the time the employees on the ninth floor realized what was happening, it was far too late.

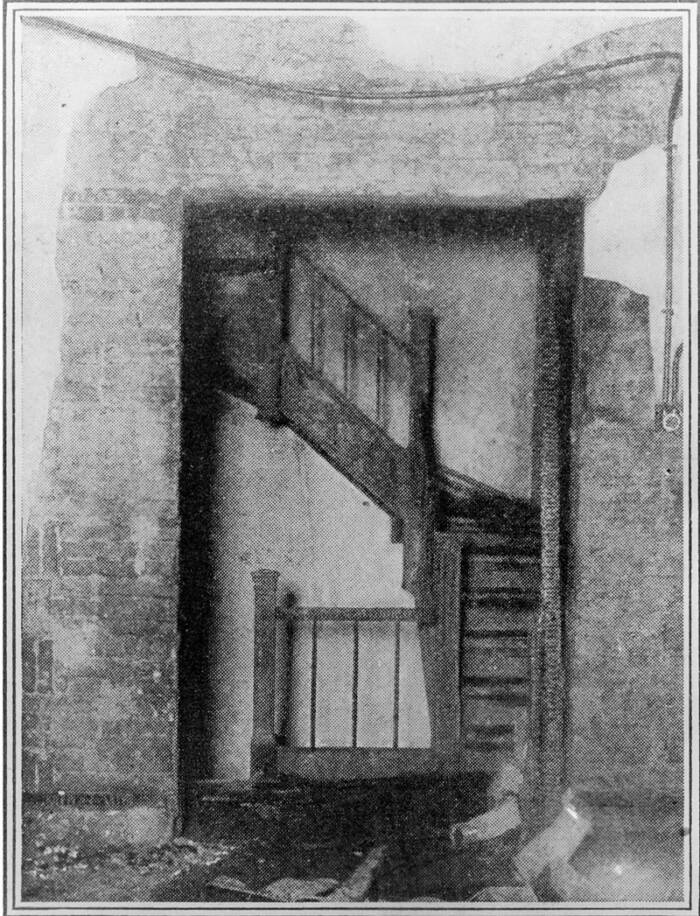

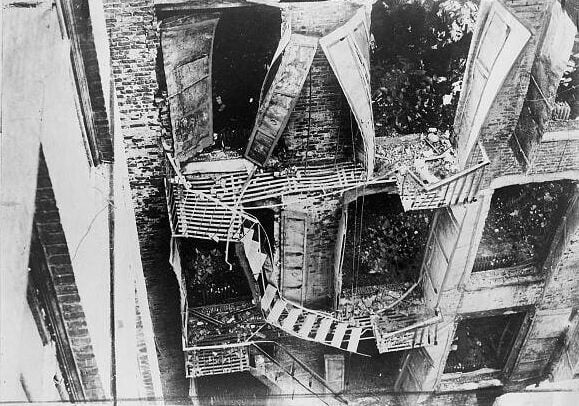

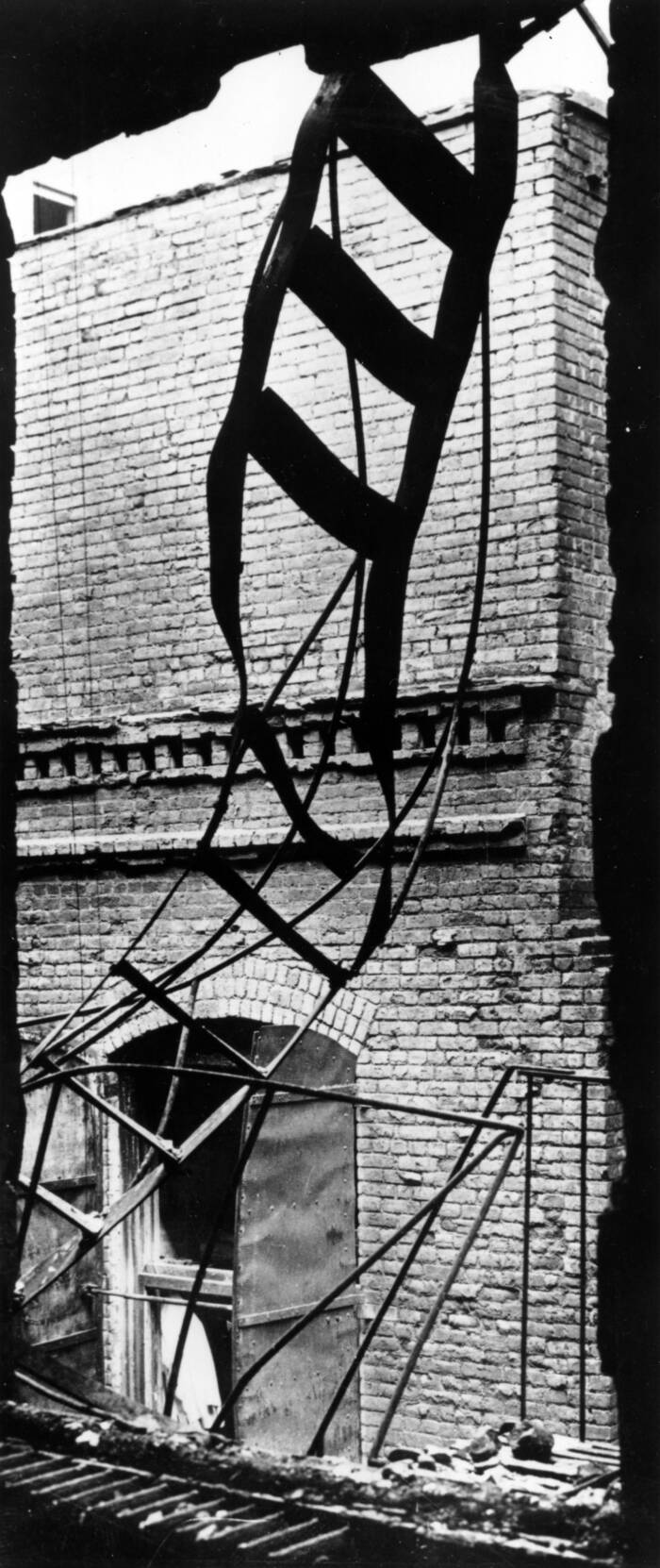

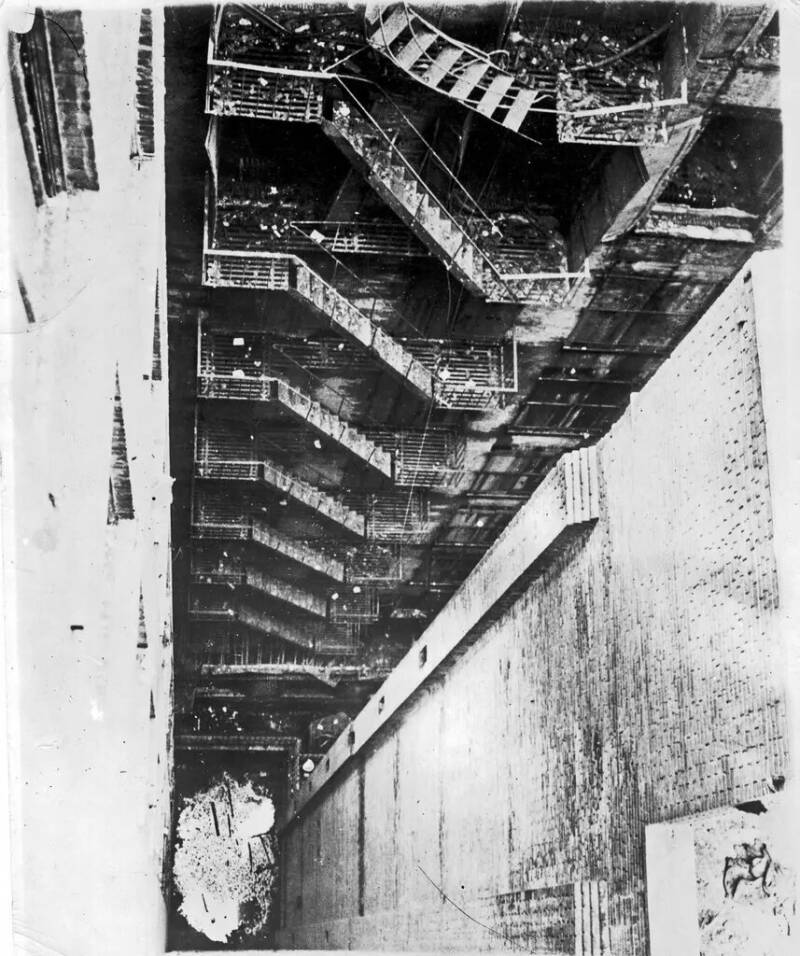

Kheel Center/Cornell University LibraryThe charred interior of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory after the fire.

The door to one of the two staircases was locked to prevent theft. The other door opened inward, and as panicked men and women rushed toward it, they effectively blocked themselves in. What's more, the fire escape that was supposed to serve as the building's third staircase collapsed as workers piled onto it. And the single functional elevator could hold only 12 people at a time and broke down due to the heat after just four trips.

Although the fire department was on the scene, their ladders only reached the seventh floor, and their nets ripped from the force of bodies falling 100 feet into them.

Everyone left on the ninth floor was trapped.

Many employees chose to jump to their deaths rather than wait for the fire to burn them alive. One witness, Louis Waldman, wrote about the horrors he saw in his book Labor Lawyer:

When we arrived at the scene, the police had thrown a cordon around the area and the firemen were helplessly fighting the blaze. The eighth, ninth, and 10th stories of the building were now an enormous roaring cornice of flames...

Horrified and helpless, the crowds — I among them — looked up at the burning building, saw girl after girl appear at the reddened windows, pause for a terrified moment, and then leap to the pavement below, to land as mangled, bloody pulp. This went on for what seemed a ghastly eternity. Occasionally a girl who had hesitated too long was licked by pursuing flames and, screaming with clothing and hair ablaze, plunged like a living torch to the street.

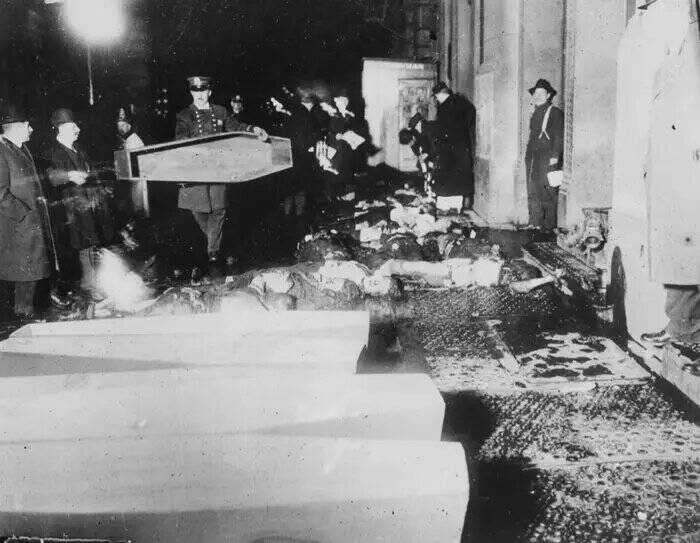

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire burned for just 18 minutes, but by the time it had been extinguished, 146 people were dead.

The Public Outcry Following The Fire And The Trial Of Blanck And Harris

In the immediate aftermath of the fire, Max Blanck and Isaac Harris went on an intense advertising campaign to uphold the company's reputation as a respectable business. They spoke to reporters and publicly made comments stating that their company adhered to the standard safety procedures and that the disaster was just that: a tragic accident.

Despite these efforts from the company heads, the public outcry that followed the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire was thunderous. On April 2, the National Women's Trade Union League organized a protest at the Metropolitan Opera House that attracted thousands of attendees.

There, the leader of the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union (ILGWU), Rose Schneiderman, told the crowd: "I would be a traitor to these poor burned bodies if I came here to talk good fellowship... Too much blood has been spilled. I know from my experience it is up to the working people to save themselves. The only way they can save themselves is by a strong working-class movement."

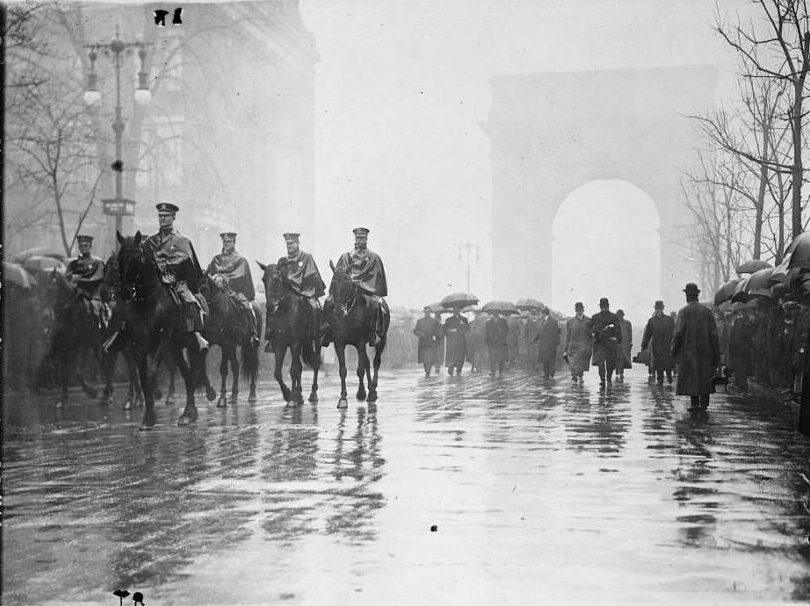

National Park ServiceCrowds surround the Asch Building following the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire.

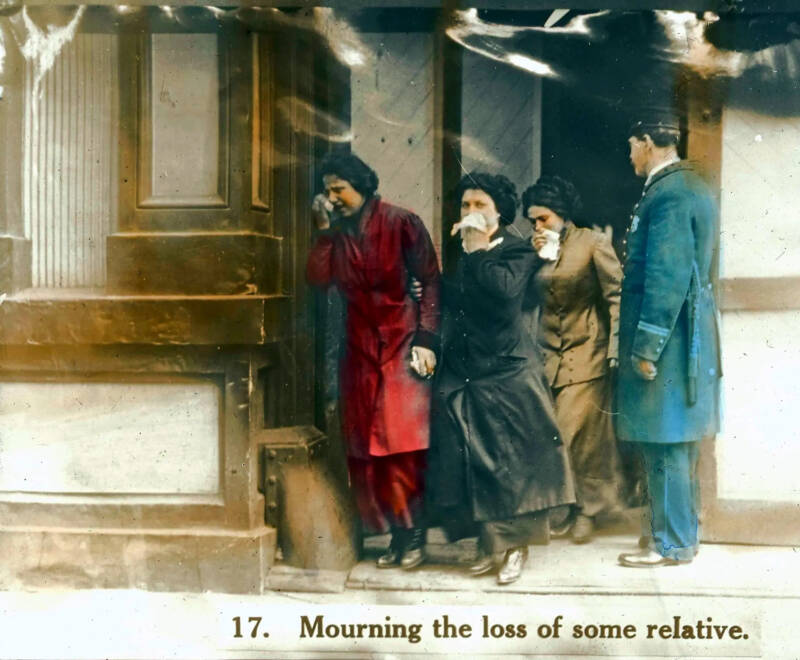

Three days later, the ILGWU held a massive funeral procession through Manhattan for the victims of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire. More than 100,000 mourners marched in support, while another 300,000 people watched from the sidewalks.

It was clear that the citizens of New York City were not going to forget about the disaster anytime soon — and they wanted justice for the victims.

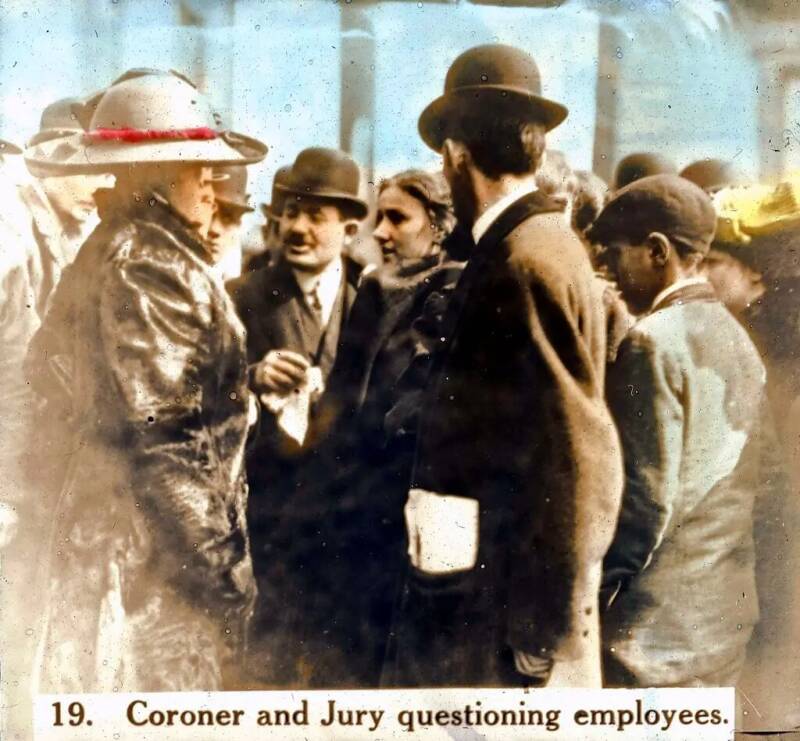

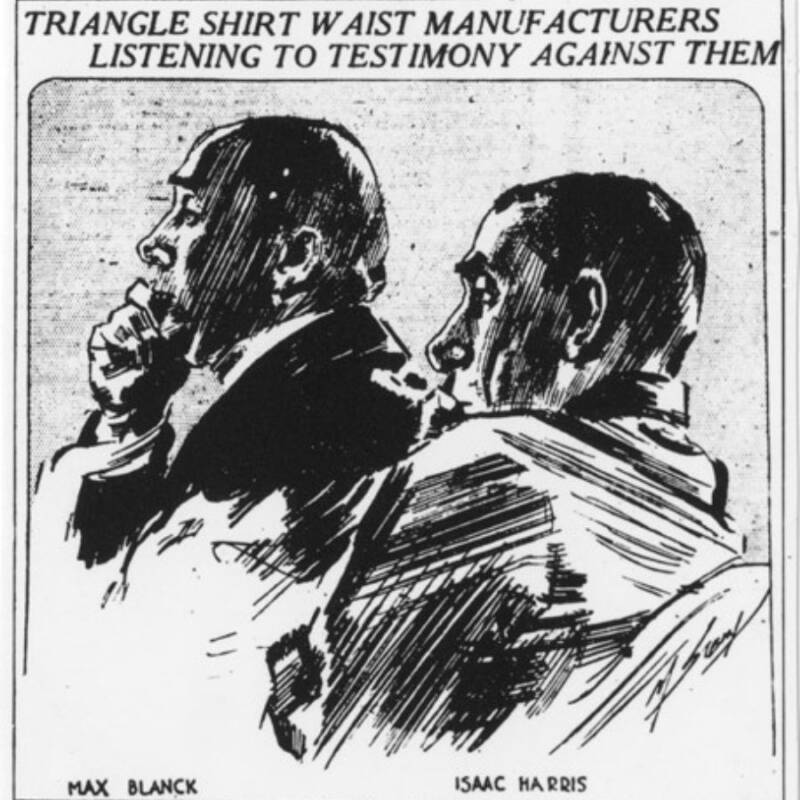

Just over two weeks after the fire, on April 11, a grand jury indicted Blanck and Harris on charges of manslaughter. During their three-week trial that December, the jury had to determine if the factory owners knew about the illegally locked door. If so, they would be guilty of violating the Labor Code and thus legally responsible for the deaths of the factory workers.

Kheel Center/Cornell University LibraryA sketch of Max Blanck and Isaac Harris during their trial in December 1911.

Ultimately, a jury could not find the men guilty without reasonable doubt, so the two were acquitted of all charges.

The verdict enraged both the city's workers' rights unions and the families of the victims. After two dozen civil suits were brought against Blanck and Harris, the men agreed to pay out $75 for each person who died in the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire. Of course, the company's insurance policy had paid out $60,000 more than Blanck and Harris lost in the disaster — meaning they profited over $300 per victim even after paying the grieving families.

While Blanck and Harris never saw repercussions for their role in the fire, however, the tragedy did have a lasting impact on labor laws.

The Legacy Of The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire

In the years following the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, New York City overhauled building codes and workplace safety standards, passing more than 30 new laws to prevent similar tragedies. These changes came with the support of garment industry labor unions, which had seen their numbers explode after the disaster.

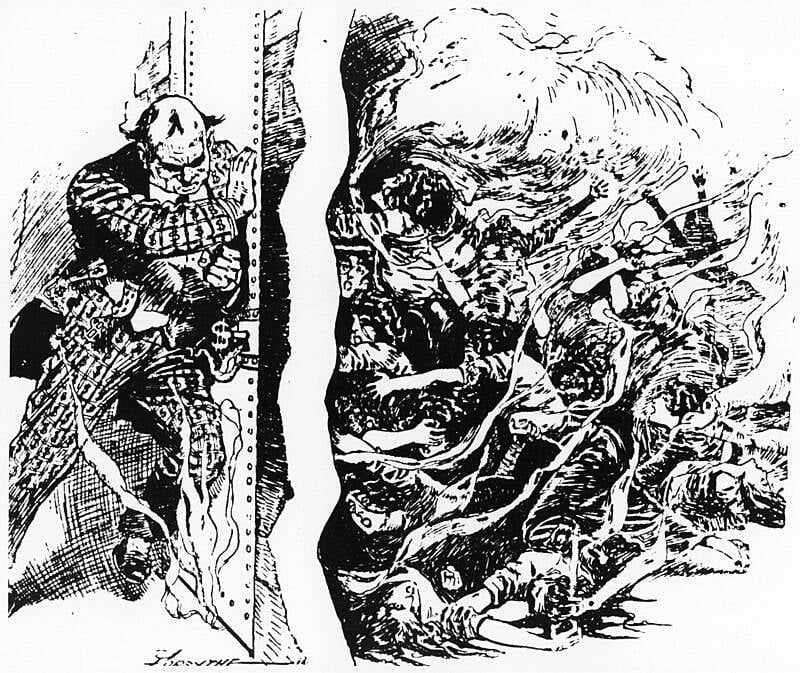

Kheel Center/Cornell University LibraryA political cartoon depicting a factory owner covered in symbols of wealth holding a door closed while workers trapped inside struggle to escape a fire.

The fire also sparked a shift when it came to opinions on workers' rights. No longer did people readily agree that workplace safety should be left to the discretion of business owners. Instead, many Americans fought for more rigorous government oversight and regulations to prevent future senseless tragedies.

The Asch Building still stands, though it's now known as the Brown Building. Today, it houses classrooms and laboratories for New York University's chemistry and biology departments.

Google MapsNew York University started using the eighth floor of the Asch Building for classrooms five years after the fire, and it was renamed the Brown Building in 1929.

For both students who attend classes in the historic structure and the countless pedestrians who walk past it every day, the building serves as a living reminder of the tragedy that took place there more than 100 years ago.

After reading about the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, go inside the story of the Hindenburg Disaster that took 36 lives. Then, discover 22 photos from the Great Molasses Flood that killed 21 people in Boston in 1919.