In the 1840s, Dr. James Marion Sims perfected his surgical skills by operating on enslaved black women without anesthesia.

In the 1840s and ’50s, an Alabama surgeon named J. Marion Sims successfully performed the first surgery to correct a condition that had long ostracized women after childbirth. Then, he invented the tool every gynecologist uses today in their exams: the speculum. For these contributions and more, Sims was hailed the “father of modern gynecology.”

But how James Marion Sims came to patent his experimental surgeries and tools has been scrutinized in recent years, as his subjects were enslaved black women he owned.

The Medical Breakthroughs Of J. Marion Sims

Born in 1813, James Marion Sims attended medical school in Philadelphia before settling in Alabama to practice medicine in 1835.

Sims reportedly had little interest in the “diseases of women.” He once wrote, “If there is anything I hated, it was investigating the organs of the female pelvis.”

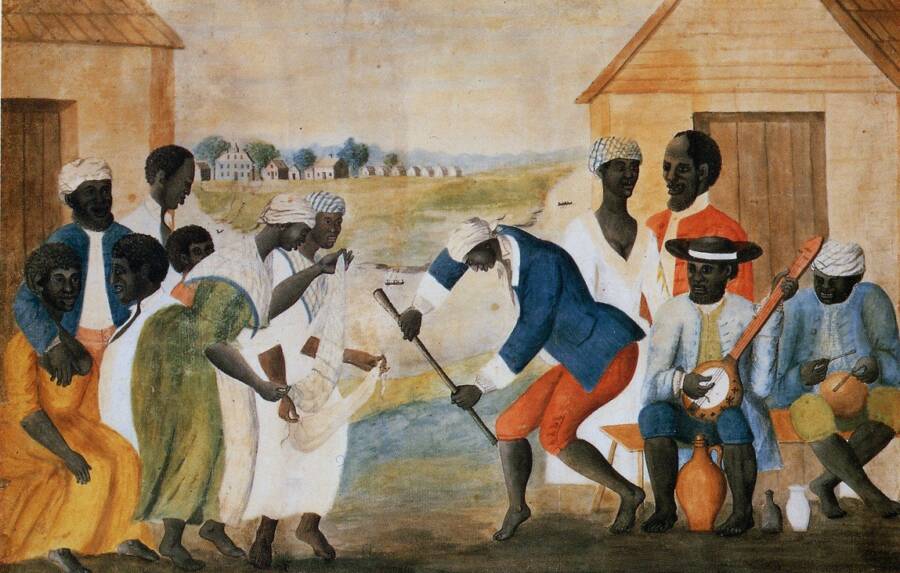

John Rose/Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art MuseumA late 18th-century depiction of slaves on a plantation. As a doctor in the deep south, J. Marion Sims had his pick of enslaved test subjects who couldn’t say otherwise.

But in 1845, a slave owner called on Sims to help his 18-year-old slave named Anarcha who had been suffering through 72 hours of labor. Sims successfully delivered the newborn only to discover that the hard labor had left Anarcha with a condition called a vesicovaginal fistula.

Vesicovaginal fistulas were common in women who had difficult labors and were holes that formed between a woman’s vagina and bladder that resulted in incontinence, an embarrassing and often isolating condition. It was once considered to be impossible to cure.

Over the next four years, Sims performed 30 experimental operations on Anarcha to cure her condition. When he did, he went on to relieve Empress Eugenia of France of this condition, as well.

As other owners called on Sims to treat their slaves, the surgeon developed a new system: He purchased these patients for the purpose of surgical experimentation. Sims explained that, “The owners agree[d] to let me keep them (at my own expense).”

The surgeon saw this as a major advantage because “there was never a time that I could not, at any day, have had a subject for operation.”

Sims later became reputable enough to open a private clinic in New York where he served wealthy, white clientele. He became a decorated surgeon in his time and invented the speculum, a tool all gynecologists use today to examine the vagina.

In 1855, he opened the nation’s first Woman’s Hospital in New York City.

The Black Women And Children Behind Sims’s Achievements

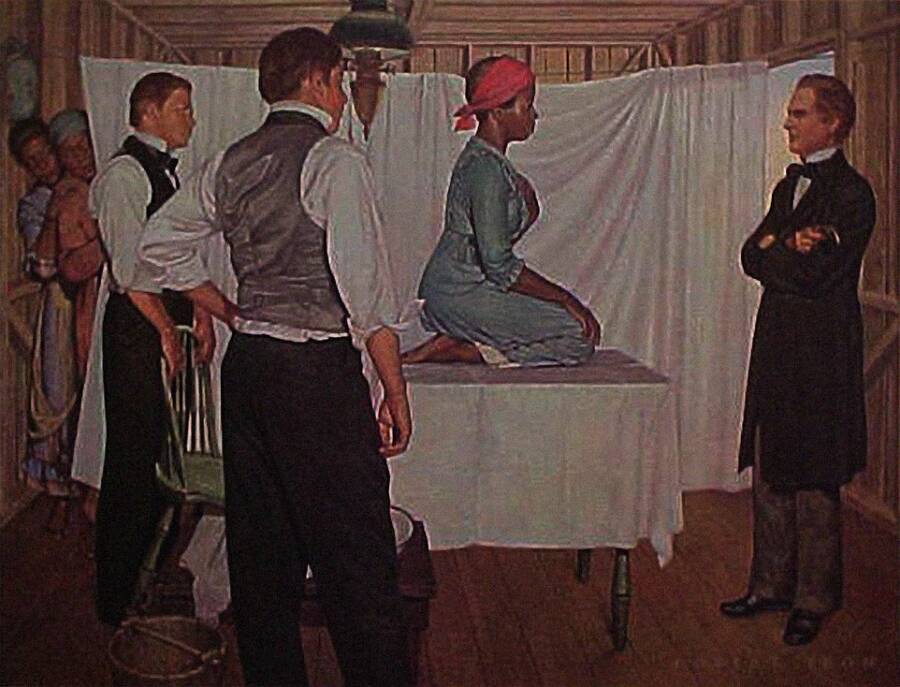

Public DomainThis is purportedly the only depiction of Lucy, Anarcha, and Betsey, as painted by Robert Thom for the “Great Moments in Medicine” series.

J. Marion Sims recorded the names of some of the black women who served as his subjects: Anarcha, Lucy, and Betsey. The identities of his other subjects have vanished.

All three of these women were young mothers suffering from incurable fistulas. And all served as Sims’s experimental subjects.

Sims invited “about a dozen doctors” to witness his experiments on Lucy, a teenager who’d recently given birth. “All the doctors… agreed that I was on the eve of a great discovery, and every one of them was interested in seeing me operate,” Sims recorded.

On Lucy, Sims performed an hour-long surgery without anesthesia. “The poor girl, on her knees, bore the operation with great heroism and bravery,” Sims wrote. “Lucy’s agony was extreme,” and she fell ill with a fever within days of the operation. “I thought she was going to die,” Sims admitted. It took months for her to recover.

Meanwhile, between 1845 and 1849, Sims performed the 30 surgeries on Anarcha to cure her fistula, all without anesthesia.

When Sims created the speculum, from a spoon, he first tested it on Betsey. The device was made to hold the vagina open so that the doctor could use both their hands to examine the patient. During his first exam with the speculum, Sims marveled, “I saw everything as no man had ever seen it before.”

But even before and after Sims experimented on enslaved women, he operated inhumanely on black children. Sims didn’t believe that African Americans could feel or think as astutely as white people and so he used a shoemaker’s tool to pry children’s bones apart and loosen their skulls for examination.

The Ethics Of Consent And Denying Anesthesia

Unknown/Wikimedia CommonsThe Sims Speculum, originally based on a bent spoon.

Sims claimed that all of his subjects consented to his experiments. He allegedly promised one slave owner, “If you will give me Anarcha and Betsey for experiment, I agree to perform no experiment or operation on either of them to endanger their lives.”

He also purportedly asked his enslaved subjects if he could test on them before he did, he wrote that they “willingly consented.”

Yet as slaves, women like Anarcha, Betsey, and Lucy could only consent. As property, what other choice did they have? Today, medical ethics standards require informed consent – which Sims could not have obtained from a slave.

Sims also performed his experimental surgeries on enslaved women without anesthetic, even though he routinely used anesthetic on his paying, white patients at the Woman’s Hospital in New York.

Like other 19th-century physicians, J. Marion Sims assumed that black people simply had higher pain tolerances than white people and therefore, didn’t require painkillers for these immensely uncomfortable surgeries.

Those who defend Sims’s choices, point out that anesthetic was new in the 1840s and rarely used in the United States. It was only by the time Sims moved to New York in the 1850s that the treatment became more common.

However, Sims routinely denied women anesthesia for fistula operations even after it had become readily available. In 1857, Sims told the New York Academy of Medicine that fistula operations “are not painful enough to justify the trouble.”

He also rarely took responsibility when his patients died after an operation, instead, he blamed “the sloth and ignorance of their mothers and the black midwives.”

James Marion Sims saw no problem with how he conducted his experiments. Indeed, modern researchers marvel at the casualness in his tone while recording his disturbing practices. As one doctor put it, he was perhaps just “a product of his era.”

The Evolving Reputation Of James Marion Sims

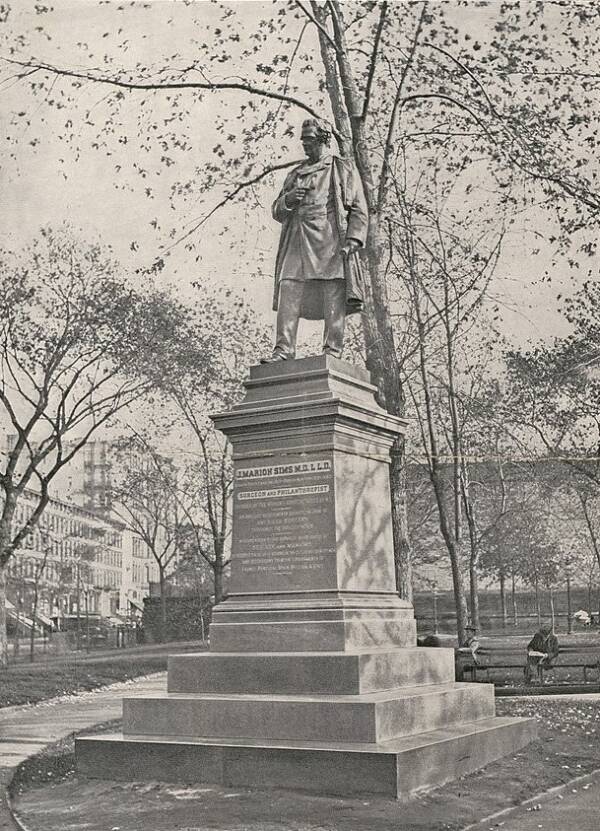

Bibliothèque interuniversitaire de Santé/Wikimedia CommonsA late 19th-century statue of J. Marion Sims, originally displayed in Byrant Park and later moved to Central Park. It was removed in 2018.

Modern historians debate the legacy of James Marion Sims.

His defenders argue that he was a man of his time who nevertheless obtained consent from, and cured, his patients.

The American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology acknowledged in 1978 that, “His original three subjects might never have tolerated the pain and misery of the repeated operations had they not been slaves.” Yet, the piece concluded, “In the long run, they had reason to be grateful to Sims.”

In 1981, the Journal of South Carolina Medical Association lauded Sims for creating a new surgical procedure “almost with a magic wand.”

In 2006, Washington University surgeon Lewis Wall defended Sims in the Journal of Medical Ethics, writing, “J. Marion Sims was a dedicated and conscientious physician who lived and worked in a slaveholding society.”

But that same year, the University of Alabama at Birmingham removed Sims from their display of the “Medical Giants of Alabama.”

Ferdinand Freiherr von Miller/Wikimedia CommonsThe statue of J. Marion Sims before it was relocated to Greenwood Cemetery in Brooklyn.

In 2017, a vandal sprayed “RACIST” on a statue of J. Marion Sims in Central Park. In response to calls to remove the statue, the prestigious journal Nature published an unsigned editorial defending Sims’s statue, which declared “Removing Statues of Historical Figures Risks Whitewashing History.” After the editorial created a firestorm of criticism, Nature reversed itself, retitling the editorial, “Science Must Acknowledge Its Past Mistakes and Crimes.”

Reassessing the legacy of James Marion Sims in the 21st century does not mean denying his medical contributions, but it does require that we place them in a social context. Instead of ignoring the black women subjected to Sims’s experimental treatments, we must acknowledge them.

In 2018, New York removed the J. Marion Sims statue from Central Park, relocating it to Sims’s burial site in a Brooklyn cemetery.

The city also replaced the original plaque that only told of Sims’s medical achievements. In its place, the new plaque recognizes the roles of Betsey, Lucy, Anarcha, and others in the history of medicine.

J. Marion Sims wasn’t the only doctor who violated medical ethics. Next, learn about the history of body snatching and then, read about the Tuskegee syphilis study that used black Americans as guinea pigs.