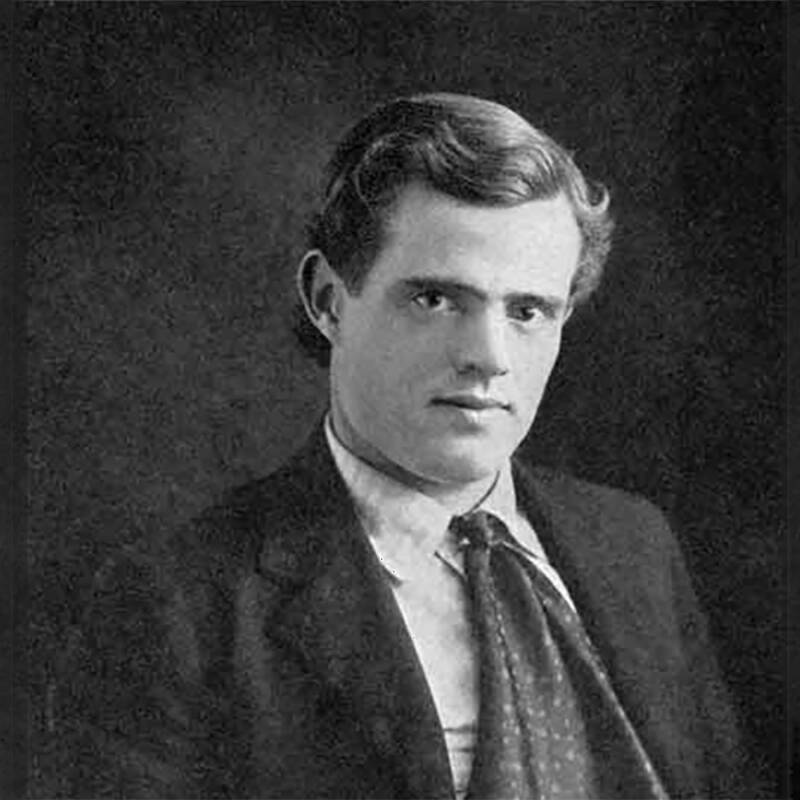

From adventurer to author to activist, John Griffith London led a dramatic life in keeping with his celebrated novels like "White Fang" and "The Call of the Wild."

Jack London was the kind of man who fully embodied the spirit of the time in which he lived — for better and for worse.

London lived the life of a rugged individualist starting at the age of just 14, embarking upon various adventures that would soon inspire his prolific writing career. Widely beloved to this day, works like The Call Of The Wild and “To Build a Fire” capture the daring exploits that mark both London’s writing and his own life.

But controversy has come to cloud his legacy as well. A product of a less tolerant time, Jack London penned divisive works and advocated for contentious causes, eugenics chief among them, that would hurt his reputation with some modern audiences.

In the end, though Jack London would live just 40 years before dying in 1916, he experienced more adventure than one could expect from a lifetime twice as long.

The Early Adventures Of A Young Jack London

Wikimedia CommonsJack London, nine, with his dog Rollo circa 1885.

Jack London was born John Griffith Chaney on January 12, 1876, in San Francisco, California. His mother, Flora Wellman, was a music teacher and a spiritualist who claimed to channel the spirit of the Sauk chief Black Hawk.

London was an illegitimate child. His father was likely a traveling astrologer named William Chaney, but he left before London was born and his mother married a disabled Civil War veteran named John London in 1876.

Wellman employed the services of an African-American woman and former slave named Virginia Prentiss to help take care of her young child. With Prentiss, London would form a deep maternal bond and she would play an active role throughout his life.

The family moved to Oakland where London attended grade school. When he was eight years old, London recalled stumbling upon a copy of the novel Signa at the Oakland library. Perhaps he was so drawn to the story because it featured a protagonist of similar circumstances: an illegitimate child is orphaned and forced to raise himself.

Indeed, London credits the novel for inspiring his later literary career. He wrote of his young self experiencing the novel for the first time:

“Again, deep in that beloved book of Signa, he raised his wet eyes, and ambition trod with conquering step to fame…[He stood, and] standing in the shadow of the great mountains and listening to the subdued, nocturnal song of nature, felt his genius pulse feverishly within him, and great longings and desires come over him.”

But that ambition would have to wait. His working-class family needed his help with finances and so, in 1889 at the age of 13, London went to work at a cannery.

Working in a cannery is never a pleasant experience, but at the turn of the 20th century, there was a complete lack of labor protections for children which meant that the young London toiled in 12 to 18-hour shifts.

Desperate to find a better way to help his family, London borrowed some money from Virginia Prentiss and bought a small sloop, or a one-man sailboat, and became an oyster pirate in San Francisco Bay.

The young pirate had a good run of it for a couple of months. One night’s work pilfering the private oyster beds of the Bay apparently made him more money than he earned in a month’s wages over at the cannery.

The young London grew up fast as an oyster pirate. He frequented the dockside bars and rabble-roused with fellow pirates and sailors, earning himself the nickname “The Prince of the Oyster Pirates.”

Library of CongressJack London in 1903, the year he sold The Call of the Wild, the story that would make him an international celebrity.

But London soon turned away from petty piracy and joined a seal-hunting schooner bound for Japan at the age of 16. When he returned several months later in 1893, the country was in the midst of the worst economic depression it had ever seen up to that point and after a couple of punishing factory jobs, London became a railcar vagabond for about a year.

He made it all the way to upstate New York where he served 30 days in state prison for vagrancy. Later, in a memoir about the experience, London recalled:

As regards the details of this man-handling I shall say nothing. And after all, man-handling was merely one of the very minor unprintable horrors of the Erie County Pen. I say “unprintable;” and in justice I must also say “unthinkable.” They were unthinkable to me until I saw them, and I was no spring chicken in the ways of the world and the awful abysses of human degradation. It would take a deep plummet to reach bottom in the Erie County Pen, and I do but skim lightly and facetiously the surface of things as I there saw them.

Returning to Oakland, London attended the local high school where he published his first-ever work “Typhoon off the Coast of Japan.” With the help of a friendly bar owner, London attended the University of California at Berkeley with the intention of becoming a writer.

After about a year in university, a lack of funds forced him to drop out and he would never return to finish the degree.

But that was likely for the best because that same year, word made it down to California that gold had been discovered in the Canadian territory of the Yukon, triggering one of the greatest gold rushes in history — and setting Jack London on the road to literary fame.

Prospecting For Gold In The Yukon

Bettmann/Getty ImagesView of the Chilkoot Pass on the border between Alaska and Canada’s Yukon Territory during the Klondike Gold Rush, circa 1898.

“It was in the Klondike,” Jack London would later say, “that I found myself. There nobody talks. Everybody thinks. There you get your perspective. I got mine.”

Jack London was now 21 and with the brother of his soon-to-be first wife, Captain James Shepard, he set sail along with an estimated 100,000 gold prospectors from the U.S. Hoping to make their fortune in the Yukon territory. Their ultimate destination was in Dawson City, a boomtown situated on the Yukon River near where the first gold vein had been found the previous summer.

The journey took London over the infamous Chilkoot Pass that marked the boundary between Alaska and Canada. From there, it was a 500-mile trek up the Yukon River to Dawson City which had to be completed before the river froze over in the early fall.

Of the 100,000 prospectors who left for the Yukon that summer in 1897, only about 30,000 made it to Dawson City. Jack London was one of them.

London would spend about a year in the Yukon before having to return to the U.S. afflicted with scurvy and not a penny richer for his efforts. He never found any gold in the Yukon, but the 11 months he spent among the prospectors would leave a lasting impression on him — and he on them.

“Intellectually he was incomparably the most alert man in the room, and we felt it. Some of us had minds as dull as putty, and some of us had been educated and drilled into a goose step of conventionalism. Here was a man whose life and his thoughts were his own. He was refreshing. This was my first introduction to Jack London.”

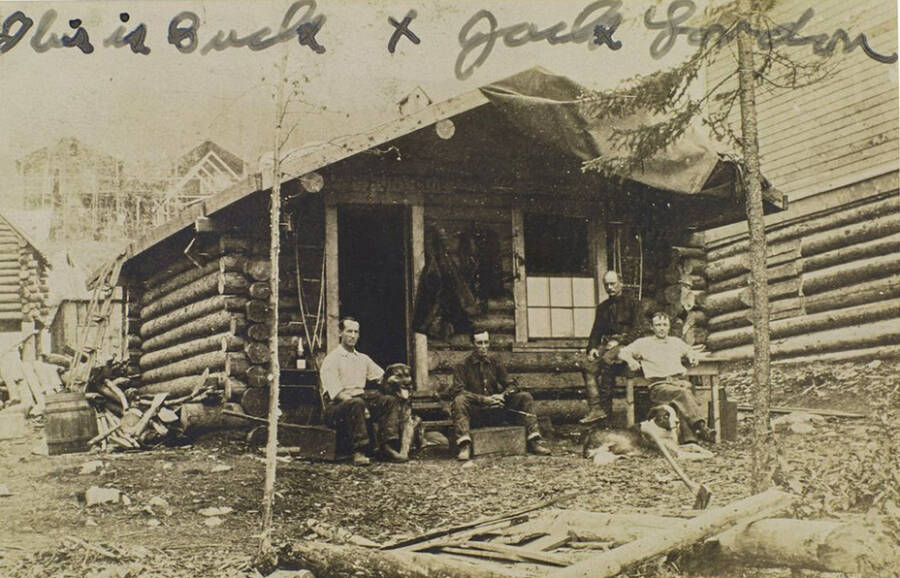

Louis and Marshall Bond, two brothers from Santa Clara, California, befriended London and let him pitch his tent next to their cabin in Dawson City. Here London made another fateful friend, one of the Bond brothers’ dogs, a Saint Bernard-Scotch Collie also named Jack.

“He always spoke and acted towards the dog as if he recognized it’s noble qualities, respected them, but took them as a matter of course,” Bond later wrote. “It always seemed to me that he gave more to the dog than we did, for he gave understanding. He had an appreciative and instant eye and he honored them in a dog as he would in a man.”

Later, London would write to Marshall Bond and confirm that Jack had been the inspiration for Buck, the canine protagonist of his most popular work, The Call of the Wild.

Jack London Collection/The Huntington Library/San Marino, CaliforniaA photo of the Bond brothers’ cabin in Dawson, City, Yukon Territory. The dog on the left is Jack.

London’s Early Writing Career And Commercial Success

After returning from the Yukon empty-handed, Jack London became convinced that his only shot at success would be as a writer. He dedicated himself to the craft and adhered to a strict personal regiment of writing 1,500 words a morning.

He tried to place several short stories with different publications but initially found little success. When The Overland Monthly offered him a meager sum for his story, “To the Man on the Trail,” and was then late on their payment, London came close to giving up entirely.

His luck turned though when another magazine, The Black Cat, paid him $40 for his story “A Thousand Deaths.”

By 1900, the cost of printing a publication had dropped considerably with the advent of more efficient technologies. Consequently, a burgeoning magazine industry started to take off in the States. Desperate for content to fill their pages, short fiction was suddenly in high demand and so London churned out stories. He wrote tales based on his experiences at sea and in the “last frontier” of the Yukon.

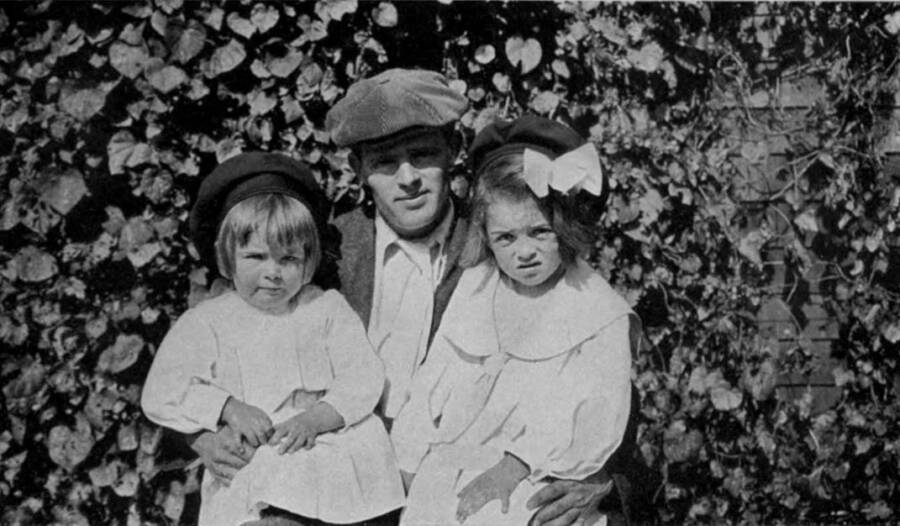

Wikimedia CommonsJack London with his two daughters, Becky (left) and Joan (right), from his first wife, Elizabeth Maddern.

That same year, London made $2,500 selling his fiction which would be equal to about $76,000 in today’s dollars. Now making a comfortable income, he married his first wife, Elizabeth “Bess” Maddern, and they had two daughters together.

Having gone to the Yukon with a general sense of social consciousness, he returned to the U.S. as a hardened socialist and would remain one for the rest of his life. He ran for mayor of Oakland in 1901 and 1905 as a socialist candidate, though he lost both elections.

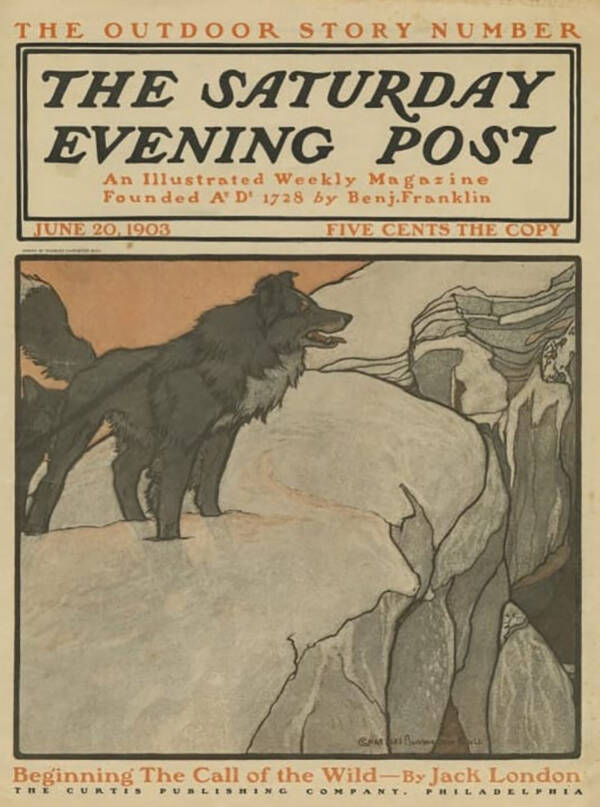

Wikimedia CommonsThis cover of The Saturday Evening Post features the first installment of Jack London’s novella, The Call of the Wild.

Jack London’s biggest success would come just three years later when he sold his novella The Call of the Wild to The Saturday Evening Post for $750.

That same year, Macmillan purchased the full book rights to the novella for $2,000 and promoted it heavily, turning it into a runaway international bestseller.

Nearly overnight, Jack London became a celebrity in both the U.S. and Europe. In the era of the States’ “rugged individualism” and the late-Victorian era in England, London’s masculine adventures were fodder for the literary scene while his political activism and spartan appearance only added to his public appeal.

The novelist E.L. Doctorow said that London was “a great gobbler-up of the world, physically and intellectually, the kind of writer who went to a place and wrote his dreams into it, the kind of writer who found an Idea and spun his psyche around it.”

Lingering Controversies, From Racism To Eugenics

Jack London with friends on the beach in Carmel, California, including author Mary Hunter Austin. Circa 1902-1907.

Jack London’s works were often described as a contradictory hodgepodge of ideas and influences of the era. He mixed the survival-of-the-fittest-ethos of social Darwinism with socialist idealism, effectively combining the idea of an equal society for all while also maintaining racist views.

Indeed, London’s perspectives on race were about as racist as you would expect from a white, public intellectual in early 1900s America.

This era was marked by scientific racism, which used such pseudoscientific theories like phrenology to justify discrimination. London’s racist views, however, may have had more nuance than other prominent public intellectuals of his time. Perhaps this was due in part to his closeness with Virginia Prentiss.

Several of his short stories feature positive portrayals of different ethnic groups. Some of his protagonists were diverse too. As a war correspondent during the Russo-Japanese War in 1904, London wrote highly of the Japanese subjects in his reports back to the U.S.

London summed up his views on race in a letter to the Japanese-American Commercial Weekly in 1913:

“The nations and races are only unruly boys who have not yet grown to the stature of men. So we must expect them to do unruly and boisterous things at times. And, just as boys grow up, so the races of mankind will grow up and laugh when they look back upon their childish quarrels.”

Wikimedia CommonsJack London in 1915.

It might seem easier to conclude that Jack London’s views were sufficiently complicated by his time, but this becomes much more difficult to do when we consider his support of eugenics, and particularly his belief in the forced sterilization of mentally handicapped persons and convicted criminals.

While we may have the benefit of hindsight as to the horrors inflicted in pursuit of eugenics in the 20th century, this does not excuse London whose views were “sufficiently nuanced” enough that he perhaps ought to have known better.

Another controversy that dogged London throughout his career was the accusation of plagiarism.

He was mostly accused of lifting the story of The Call of the Wild from Egerton Ryerson Young, which London admitted he’d used as a source for the novel.

He argued that using source material on similar instances from different works did not constitute plagiarism.

London’s Untimely Death And Enduring Legacy

Charmian Kittredge married Jack London in 1905 and was said to be the love of his life. She is buried beside him on the site of their ranch in Sonoma County, California.

Jack London met Charmian Kittredge, a progressive “modern woman,” in 1900 and the two struck up a friendship around their shared socialist idealism. By 1903, the friendship had turned into a romantic affair and London divorced Maddern to marry Kittredge.

Unlike London’s first marriage, which both parties acknowledged was not out of love but for the practicality of having a family, Kittredge was reportedly the true love of London’s life.

They took many trips together in the South Pacific, including several to Hawaii. Together, they lived on a 1,000-acre ranch in Sonoma County, California, that London was able to purchase thanks to the success of his novels.

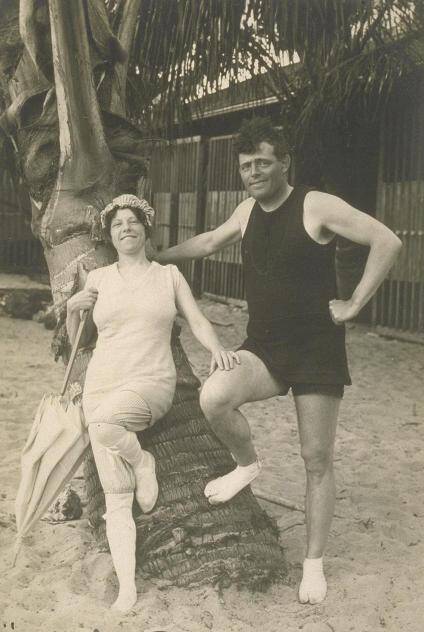

Wikimedia CommonsJack and Charmian London on holiday in Hawaii, circa 1905-1916.

“I ride out of my beautiful ranch,” London wrote. “Between my legs is a beautiful horse. The air is wine. The grapes on a score of rolling hills are red with autumn flame. Across Sonoma Mountain wisps of sea fog are stealing. The afternoon sun smolders in the drowsy sky. I have everything to make me glad I am alive.”

It was on his ranch in 1916, at the age of 40, that Jack London died of uremic poisoning after years of battling various ailments from dysentery and rheumatism.

After a writing career of just 18 years, he had written 20 novels, more than two dozen other books, and even more short stories.

A celebrity and man of his time, London suffered the same fate as many other early 20th-century writers, namely, publishing works that extolled manly virtues and dabbled in seemingly cutting edge pseudoscientific ideas.

These works were heavily criticized following World War I and became almost despised after World War II, and London’s reputation suffered in the century since his death as a result.

There has been renewed interest in his work in recent years, however, as scholarship attempts to rehabilitate his image. Meanwhile, his most famous and beloved work will be readapted for film for the first time in decades. There is bound to be some reflection on the wilderness lost to climate change in this adaptation, too, as the Chilkoot Pass gradually melts.

Indeed, there are few better places to go than Jack London’s work to remember that battling nature was once a respectable personal trial and not the civilizational crisis of our time.

Now that you’ve read about the life of American author Jack London, read about another famous American author who doubled as a wartime journalist, Ernest Hemingway. Then, read these 25 quotes from famous British author and socialist George Orwell about art, war, and the nature of truth itself.