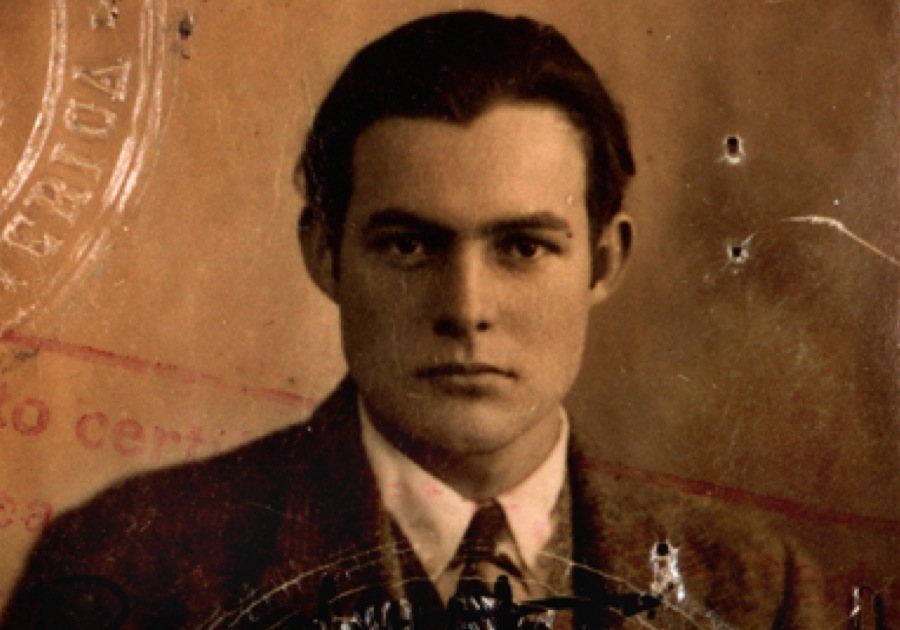

Hemingway’s 1923 passport photo. Source: Congressional Archives

In his memoir A Moveable Feast, Ernest Hemingway recalls what he told himself when he felt he couldn’t write:

“I would stand and look out over the roofs of Paris and think, ‘Do not worry. You have always written before and you will write now. All you have to do is write one true sentence. Write the truest sentence that you know.’ So finally I would write one true sentence, and then go on from there. It was easy then because there was always one true sentence that I knew or had seen or had heard someone say.”

Hemingway’s determination to write simple, true sentences began in his years as a journalist. Before the novels and the Nobel Prize, he sharpened his literary tools as a reporter, first in Kansas City, then in Toronto, and finally as a European correspondent.

From the High School Newspaper to the Kansas City Star

One of Hemingway’s high school teachers identified the germ of Hemingway’s talent when he was sixteen years old and living in Oak Park, Illinois. She put him on the staff of the high school newspaper, the Trapeze. A year later he was an editor. His prose, as tedious and forgettable as anyone else’s teenage literary flailings, included lines such as this description of a nerd outsmarting a jock at a debate:

“There is also something gratifying in seeing a huge, athletic fellow, who usually emphasizes his remarks by poking his fist under his opponent’s nose, be squelched, crushed and verbally sat upon by a little ninety-eight pound lad who had hitherto been in abject awe of the rough person with the large mouth.”

After graduating from high school, Hemingway wanted to join the army, but at seventeen he was too young. Instead he moved to Kansas City. His uncle had gone to college with the editor of the Kansas City Star and got young Ernest a job.

At the age of 18, Ernest Hemingway went to work as a “cub reporter” in Kansas City. Source: Wikimedia Commons

As with every other “cub reporter,” the Star issued Hemingway a style sheet (pdf) when he joined the staff in 1917. This Hammurabi-style code listed 110 mandates, including:

• Use short sentences. Use short first paragraphs. Use vigorous English. Be positive, not negative.

• Eliminate every superfluous word.

• Numbers less than 100 should be spelled out, except in matter of statistical nature, in ages, time of day, sums of money and comparative figures or dimensions.

• Do not use evidence as a verb.

Much of Hemingway’s reporting at the Star was published without a by-line, but we know he covered petty crimes and the arrival of imminent persons at the train station. Two stories, each definitely Hemingway’s, stand out from his seven months of reporting in Kansas City. In the first of these, “At the End of the Ambulance Run,” the young reporter simply spends a night in an emergency room and records what he sees. The article shows his ability to convey the emotional truth of a scene with sparse details and finely chosen lines of dialogue. It begins,

“The night ambulance attendants shuffled down the long, dark corridors at the General Hospital with an inert burden on the stretcher. They turned in at the receiving ward and lifted the unconscious man to the operating table. His hands were calloused and he was unkempt and ragged, a victim of a street brawl near the city market. No one knew who he was, but a receipt, bearing the name of George Anderson, for $10 paid on a home out in a little Nebraska town served to identify him.

The surgeon opened the swollen eyelids. The eyes were turned to the left. ‘A fracture on the left side of the skull,’ he said to the attendants who stood about the table. ‘Well, George, you’re not going to finish paying for that home of yours.’”

Years later, Hemingway would say his favorite piece from his time in Kansas City was “Mix War, Art, and Dancing.” Ostensibly about a singles-night at the Fine Arts Institute where returned soldiers and local young ladies had the chance to meet and dance, Hemingway focuses his readers on a woman who would never be invited to this party:

“Outside a woman walked along the wet street-lamp lit sidewalk through the sleet and snow.”

Though he never names her profession in the piece, he would later say that the article was “very sad, about a whore.” Though somewhat melodramatic (“After the last car had gone, the woman walked along the wet sidewalk through the sleet and looked up at the dark windows of the sixth floor”), this article signaled Hemingway’s intention to tell truer stories than facts themselves allowed.

Hemingway in his American Red Cross uniform in in Italy in 1918. Source: John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum

Hemingway worked at the Star from October 1917 until the spring of 1918 when he left for Italy to serve as an ambulance driver for the American Red Cross. One day in Italy he left his post to take chocolates to the Italian troops on the front line. The troops came under fire. A mortar exploded, and Hemingway would spend the next six months in a Milan hospital healing. There, he fell in love with his nurse, but after he returned to the United States, she wrote him to say she wanted to be with another man.