A smuggler of epic proportions, Jean Lafitte had an army of privateers with as many as 1,000 men — ultimately making him an invaluable asset for America in the War of 1812.

Though much of his life has been obscured by legend and time, the story of 19th-century French pirate Jean Lafitte is nonetheless one of intrigue, crime, and heroics.

Lafitte was smuggling slaves and goods into America, which had imposed an embargo on France and Britain, when he was suddenly dispatched to help General Andrew Jackson to fight the British in the War of 1812.

Louisiana Digital LibraryThough he was a smuggler and privateer, Jean Lafitte aided the U.S. army and was pardoned for his crimes afterward.

Though he was described by General Jackson as a “hellish banditi,” Lafitte proved to be invaluable in battle and served a pivotal role in an American victory.

But questions about his story linger, including how and where, exactly, he died.

Jean Lafitte Becomes A Pirate Commander

As is true of so many elusive characters of his time, the details on Lafitte’s background are ambiguous. By some accounts, he was born in the French colony of San Domingo, which is now Haiti. By others, he was born Jewish in Bordeaux, France. But most sources agree that he was likely born between 1780 and 1782.

How many siblings exactly Lafitte had is contested, but it is known that he shared a special bond with at least two of his older brothers, Pierre and Alexandre.

Wikimedia CommonsJean Lafitte smuggled African slaves into Louisiana alongside his two brothers.

According to Patriotic Fire: Andrew Jackson and Jean Lafitte at the Battle of New Orleans by Winston Groom, the author of Forrest Gump, all three boys received a rigorous education in Haiti and were sent off to a military academy on St. Kitts.

Also by this account, Alexandre — eldest among the three brothers — had allegedly gone off to become a pirate and attack Spanish ships that sailed through the Caribbean. He would often come home to Haiti and regale his younger brothers with his adventurous tales.

Perhaps that is why the Lafitte brothers moved to Louisiana in 1807 to become privateersmen — an occupation that was neither respectable nor safe. At the time, America had placed a ban on trading with the British in an effort to avoid becoming involved in the Napoleonic Wars in Europe and the scarcity of goods in America made for a lucrative business in smuggling.

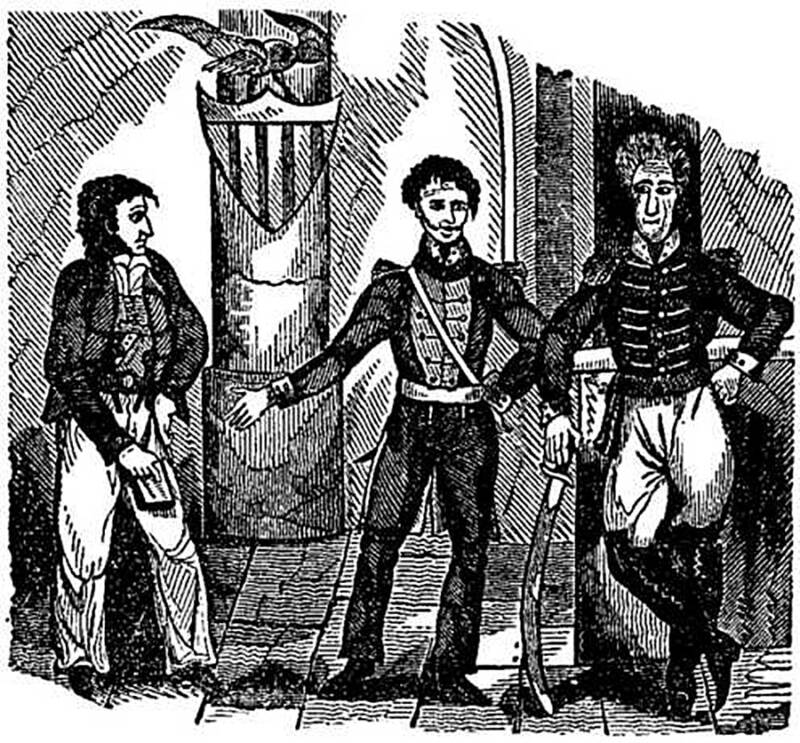

Louisiana Digital LibraryJean Lafitte (left) and his brothers Pierre (center) and Alexandre became notorious pirates.

According to Groom, the brothers became embroiled in the schemes of Joseph Sauvinet, a prominent French businessman in New Orleans. At the time, Jean Lafitte was something of a presence. At six feet tall, he was described as conniving, intelligent, and prone to taboos like gambling and drinking. He would be a successful pirate.

Jean Lafitte and his team of smugglers operated out of Louisiana’s southeastern Barataria Bay where they had established their headquarters on Grand Terre Island. Consequently, Lafitte and his band of privateers became known as the pirates of Barataria and they attacked and looted more than 100 government vessels, pillaging their precious cargo, not the least of which were slaves.

They held lavish auctions in the southern Louisiana swamps and Lafitte hoarded an arsenal of cannons and gunpowder. He potentially employed as many as 1,000 men, including free Black men and runaway slaves.

From their island of stolen goods, the Barataria pirates evaded the law as best they could. Though the Lafitte brothers were occasionally jailed they usually managed to escape. But the spoils were not to last as in 1812, America went to war against the British.

The War Of 1812

In 1814, the British courted Lafitte and the Barataria pirates to join them in their fight against America and aid in an attack on New Orleans. They offered the pirates land and a full pardon for their crimes should they join them.

The British also offered Lafitte 30,000 British pounds or the equivalent of $2 million today to convince his followers to join their cause. In the event British forces succeeded in their attack against New Orleans, they promised to free his brother, Pierre, who was in jail and set to be hanged.

Furthermore, the British threatened to destroy Lafitte’s operations if he refused, so the pirate told the British that he would need two weeks to prepare and promised him that his men would be “entirely at your disposal.”

Wikimedia CommonsU.S. Commodore Daniel Patterson commanded an offensive force against Lafitte and his men at Barataria in 1814.

But Lafitte had other plans. Instead, he conspired with the U.S. government. He sent a letter to a member of the Louisiana legislature named Jean Blanque in which he revealed Britain’s plan to attack New Orleans.

But state officials did not trust Lafitte and his gang of pirates, so Lafitte sent another letter and this time to Louisiana Governor William C.C. Claiborne, pleading: “I am a stray sheep wishing to come back into the fold.”

Unconvinced of his loyalty, the U.S. Navy lay siege to Grand Terre Island on Sept. 16, 1814. Under the leadership of U.S. Commodore Daniel Patterson, the Navy razed the pirate’s buildings and captured 80 men, including Lafitte’s brother Alexandre.

But Jean Lafitte remained at large.

From Pirate To Patriot

Wikimedia CommonsA depiction of Jean Lafitte discussing military strategy against the British with Gov. William Claiborne and Gen. Andrew Jackson.

While U.S. forces hunted down Jean Lafitte and his men, they also contended with the imminent threat of a British invasion.

In December 1814, a battle at Lake Borgne resulted in the capture of five American gunboats filled with armaments and several boats of prisoners. Ten American soldiers were killed while 35 others were wounded.

Finally, General Andrew Jackson summoned Jean Lafitte to negotiate a working relationship with the state legislator and a judge. Though Jackson despised the Baratarians, he was desperate for military support and he knew that Lafitte had a cache of arms, gunpowder, and cannonballs.

“I was almost out of breath, running through the bushes and mud. My hands were bruised, my clothing torn, my feet soaked. I could not believe the result of the battle.”

After the meeting, Jean Lafitte’s men were released and deployed as cannoneers and swamp guides for the U.S. troops. Lafitte himself was made Jackson’s unofficial aide-de-camp.

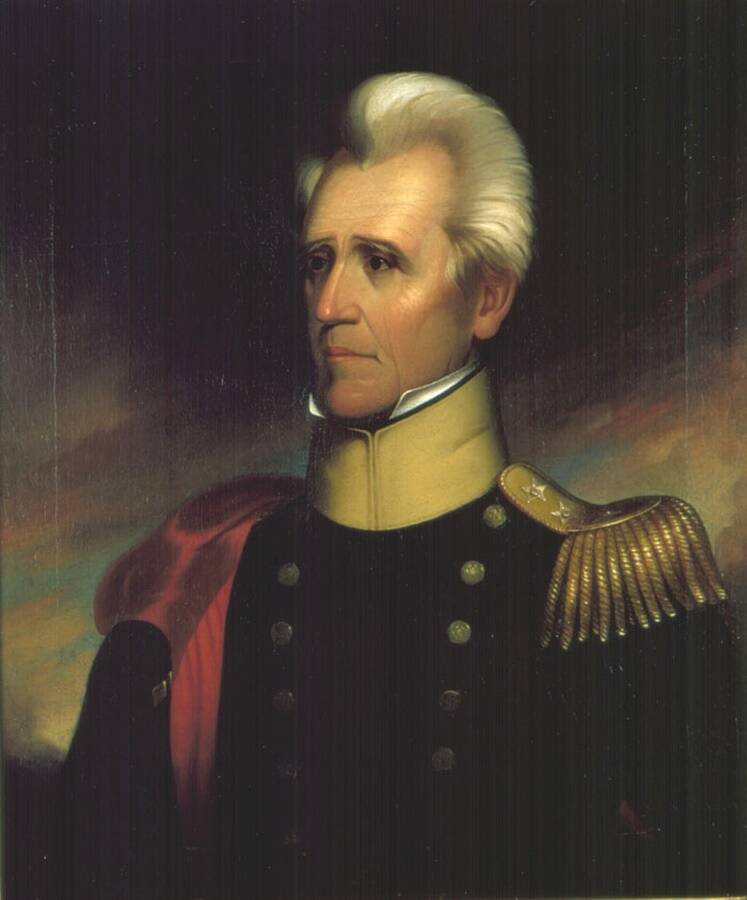

Wikimedia CommonsGen. Andrew Jackson despised Lafitte and the Baratarians before he finally enlisted their help in the war.

The Baratarians proved to be invaluable to the U.S. defense against the British. Their aid culminated in the Battle of New Orleans on Jan. 8, 1815.

Within just 25 minutes, the British Army lost nearly its entire officer corps. Three field generals and seven colonels were killed by the Baratarian-backed assault.

Wikimedia CommonsJean Lafitte and his band of pirates were crucial to America’s victory in the Battle of New Orleans.

For their role in aiding the U.S. against the British, the Baratarian pirates were pardoned by President James Madison. As though recovering from a brief reprise, Lafitte promptly returned to his smuggling ways.

A Finale Shrouded In Mystery

Jean Lafitte relocated with 500 of his men to Galveston Island in Mexico in 1816. Within two years, Lafitte rebuilt the Baratarians’ operations, capturing goods and smuggling them into the U.S.

The new colony at Galveston, which Lafitte dubbed Campeche, survived through eviction threats from the U.S. Army and a massive hurricane that devastated the territory. The settlement was finally abandoned in 1821.

FlickrA walking path through the Jean Lafitte National Historical Park And Preserve.

As to Jean Lafitte’s fate after Galveston, one can only speculate. Some claimed he was killed out at sea while others claimed he had succumbed to disease, was captured by the Spanish, or even murdered by his own men.

A journal that purportedly belonged to Lafitte and surfaced in the 1940s alleged that he moved to St. Louis where he assumed a new life as John Lafflin. There he married and had a son with a woman named Emma Mortimere. According to this account, he died in Alton, Illinois, in 1854 at the age of 70.

However, the authenticity of this journal remains unknown. There are also rumors that the pirate king buried treasure around Louisiana before his old age.

Despite their history of crime, Jean Lafitte and his gang of pirates were critical to the U.S. army’s fight for New Orleans. Countless streets and communities in Louisiana, including the Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve, have been named in his honor.

Next, learn about how Davy Crockett went from frontiersman to politician to hero of the Alamo. Then, meet Bartholomew Roberts, perhaps the most successful pirate of all time.