After escaping persecution in Europe, these Jewish scholars found hatred in its American form — and a deep bond with historically black colleges and universities.

The Nazi Party sought to destroy all forms of Jewish life, and Jewish academics were among the first victims of the party’s fatal endeavors. In 1933, just months after coming to power, the Third Reich passed a law that barred non-Aryans from holding civil and academic positions, thereby dismissing around 1,200 Jews who held academic posts in German universities.

Over the course of that year and throughout World War II, many academics — established and burgeoning alike — fled Germany. Most went to France, but some made the trek across the Atlantic Ocean for the United States.

Approximately 60 of these Jewish academics took refuge in the American South. There, they found a startling reminder that the systemic persecution that they experienced was not isolated to Germany under the Third Reich. They also found a home in the South’s historically black universities and colleges.

Anti-Semitism and the Academy

ullstein bild/ullstein bild via Getty ImagesLocals in Leissling, Germany performing mocking folk custom known as “the expulsion of Jews,” 1936.

While theoretical physicist Albert Einstein often serves as the “poster boy” for Jewish academics who quickly found a fulfilling intellectual life in the United States, his story was more of an exception than the rule.

Indeed, throughout World War II, the U.S. lacked an official refugee policy, and instead relied on the 1924 Immigration Act. This act placed a quota system on admitted immigrants, which it based on the immigrant’s national origin.

The act favored Western and Northern Europeans — and Germany had the second highest cap — but because so many German Jews sought entry to the U.S., many waited (and sometimes died waiting) on the list for years.

If a Jewish academic were to be admitted entry into the U.S., they often had to contend with the fact that academic institutions — particularly Ivy League schools — by and large did not want them there. While Princeton University welcomed Albert Einstein to the Institute for Advanced Study in 1933, many other academics did not have the same name recognition and thus were subjected to the prejudices and pretensions of the university.

At the time, Ivy League universities such as Columbia and Harvard had adopted informal quota systems to keep Jewish enrollment low. James Bryan Conant, the President of Harvard at the time, went so far as to invite Nazi Party Foreign Press Chief Ernst Hanfstaengl to campus in June 1934 for an honorary degree — one year after Hanfstaengl told U.S. diplomat James McDonald that “the Jews must be crushed.”

While students often held demonstrations against administrative displays of Anti-Semitism, the message seemed clear: if you were a Jewish intellectual seeking sanctuary in the U.S., you may not have found it in the academy — at least among the more prominent academic institutions.

Down South

Jack Delano/PhotoQuest/Getty ImagesPhoto taken at the bus station, showing the Jim Crow signs of racial segregation, Durham, North Carolina, May 1940.

That hardly meant that Jewish academics in the U.S. would simply stop seeking work in academia, however. For some, it meant that they would set their sights south — particularly among historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs).

As Ivy Barsky, Director of the National Museum of American Jewish History, would say, the individuals who ended up in the South were “not big names like Albert Einstein, who were able to find jobs at the elite universities, but mainly newly-minted PhDs with nowhere else to go.”

These individuals — who taught at HBCUs in Mississippi, Virginia, North Carolina, Washington, D.C., and Alabama — were in for a rude awakening.

In the 1930s, the American South was in an economic tail spin, which only had the effect of increasing racial tensions. Indeed, poor whites looked to African-Americans as a primary cause of their suffering — even though, as the Library of Congress notes, the Great Depression hit African-Americans the hardest of all.

As such, Jim Crow laws passed around this time took on the institutions that could offer African-Americans upward mobility and thus help ensure increased, substantive equality among races over time. For instance, in 1930, Mississippi passed a law that segregated healthcare facilities and required racial segregation in schools.

This atmosphere — protracted economic malaise creating conditions for systematic persecution — was not unfamiliar to Jewish academics attempting to make a home out of the American South, yet it horrified them all the same.

As Talladega College professor Donald Rasmussen would say, “As soon as we left the Talladega campus, we found a situation of extreme apartheid that appeared as insanity to us…We were in what we might call the best of America and the worst of America.”

Indeed, in 1942 Birmingham, Al. police fined Rasmussen $28 for sitting in a café with a black acquaintance.

Other Jewish academics learned from these run-ins with the law and responded accordingly — even in the privacy of their own home. “This was a time when if blacks and whites were meeting at someone’s home, you had to pull down the shades,” author Rosellen Brown said.

“They Just Assumed That Jews Were Black”

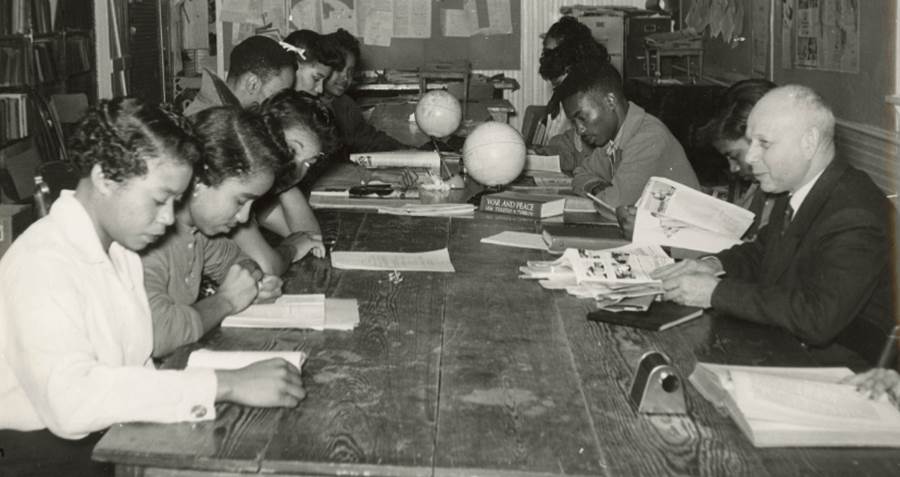

Public DomainErnst Borinski and his students in Tougaloo University’s Social Science Lab.

In spite or perhaps because of Jim Crow, and in spite or perhaps because of the Nazi Party, Jewish academics and students at HBCUs found in one another a camaraderie whose fruits would last a lifetime.

“They were the cream of German society, some of the most brilliant scholars of Europe,” Emily Zimmern, former president of the Museum of the New South, said. “They went to poorly funded black colleges but what they discovered were incredible students.”

Students likewise found role models — and perhaps unlikely bonds — in their marginalized peers.

A 1936 editorial in Afro-American highlighted the similarities that would bind them to one another. “Our constitution keeps the South from passing many of the laws Hitler has invoked against the Jews, but by indirection, by force and terrorism, the south and Nazi Germany are mental brothers.”

Still, this intellectual fraternity presented questions to some students.

“My mentor was not a black man, it was a white, Jewish émigré,” Donald Cunnigen, assistant professor of sociology and anthropology at the University of Rhode Island, told the Miami Herald. “I was thinking, ‘So what does this mean for me in terms of how I view the world and the things I want to do?’”

Cunningen was one of German-Jewish sociologist Ernst Borinski’s students at Mississippi’s Tougaloo College. Borinski would teach at the school for 36 years until his 1983 death and be buried on the campus.

One of Borinski’s students, Joyce Ladner, went on to become the first female president of Howard University, a HBCU in Washington, D.C. Years after Borinski’s death, Ladner returned to Tougaloo, and to the grave of the man whom she saw as truly transformative.

“I went to his grave…[and was just ] thoughtful about how strange it was that this little man came to a place like Mississippi and certainly had this profound impact on my life,” Ladner said. “And I had so many friends, classmates, whose lives he had also touched as well.”

Men and women like Borinski would not just leave an indelible mark on their students lives; in many ways, students would embed their teachers — icons of hope and resilience in the face of oppression — within their own experience.

“My classmates in high school couldn’t imagine there could be people so oppressed who were white,” Cunningen said. “So they just assumed that Jews were black.”

Next, learn about what happened when a white man named John Griffin toured the segregated South disguised as a black man.