As president of the Teamsters, Jimmy Hoffa battled with the government, big business, and the mob before he disappeared on July 30, 1975.

There are many questions surrounding the life and death of Jimmy Hoffa. But if you’re under a certain age, the first two you might ask are “why do some people care so much about what happened to him?” or even, “who was Jimmy Hoffa, again?”

James Riddle Hoffa was the controversial president of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters union from 1957 to 1971. His leadership was marked by both his contentious wielding of his enormous power and his cult-like popularity — as well as his longstanding ties to the criminal underworld.

But even those elements alone don’t fully explain why Jimmy Hoffa’s life story, let alone his infamously unsolved 1975 disappearance, remains so captivating?

To give those not old enough to remember Jimmy Hoffa an idea of the impact he and his vanishing had, imagine what the next 50 years of news cycles would look like if Mark Zuckerberg or Bernie Sanders just vanished tomorrow without a trace. It would be all that anyone would talk about, and in 1975, Jimmy Hoffa was that big a deal in American life.

Back then, unions were still a powerful force in the country in ways they aren’t today and Hoffa was the single most visible face of the union movement. After all, Robert Kennedy once called Hoffa the second most influential man in America, outranked in power only by the president himself.

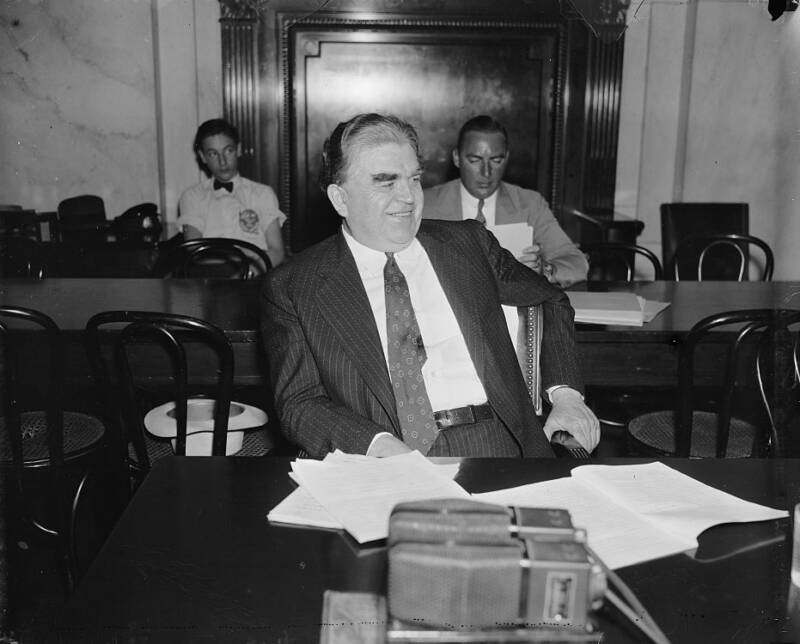

Robert W. Kelley/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty ImagesJimmy Hoffa, who gave up his position as Teamsters president after his prison sentence for fraud and bribery, sitting at a table during a Teamsters convention.

Perhaps even more than his once-great power, Jimmy Hoffa’s disappearance is what makes his larger-than-life story fascinating to this day. As with the Romanovs or the Lindbergh baby, whenever there is a high-profile suspected murder case and no body left behind, myth-making is bound to fill in the gaps.

But despite a half-century of myth-making, most authorities on the matter agree that there really isn’t much mystery about what happened to Jimmy Hoffa: he was killed by the Mafia.

Once you’ve set the wildest theories to the contrary aside, the remaining questions have only to do with the details: exactly which mob boss ordered the hit, who pulled the trigger, and what they did with his corpse. With almost no hard evidence and very few witnesses — all of whom would likely be dead by now — this cold case has remained wide open to broad speculation and self-serving fabrications.

But to understand why the Mafia killed him and why he was such a force in American life, you have to go back to the very beginning of Jimmy Hoffa’s career.

Labor Battles From An Early Age

Jimmy Hoffa — born in Brazil, Indiana on February 14, 1913 — was a labor warrior from a young age. With his father gone by the time he was seven and his last day in school coming at just 14, the young Hoffa was a manual laborer supporting his family before most other kids were graduating high school. And the labor world into which he entered was an especially unforgiving one.

An American company fighting unionization in the early 20th century would have several different resources at its disposal and most of them were violent. Often the police, sometimes private detectives, and frequently, gangs of criminal thugs could be called upon to break up strikes and other demonstrations. It was during these battles that Hoffa’s ties with organized labor were first forged.

When the Great Depression hit, several trends collided. Under the Roosevelt administration, unions gained greater protections to organize. On the other hand, with legions of people now unemployed, the steel, automotive, and other main labor industries had an endless pool of workers available to them. Everyone’s job was thus tenuous because there was always some other job seeker waiting to replace you — and so even talking about forming or joining a union could get you fired, law or no law.

Roger Higgins/Library Of CongressBernard Spindel advises Jimmy Hoffa at one of a long succession of trials and hearings in 1957.

So it was genuinely an act of bravery when in the early 1930s a 19-year-old Jimmy Hoffa joined with a small cohort of warehouse workers to protest conditions on the job.

They were working at the train-loading docks of a food distribution center for the Kroger grocery store chain in Detroit. The pay was low and workers often had to wait around, unpaid, for what amounted to hours of on-call time. The hourly wage would only kick in once the shipments of produce showed up.

The workers chose an opportune moment to strike — literally. A shipment of strawberries came in and were sitting on the loading dock waiting to be put on ice to prevent spoilage when the warehouse workers refused to move them unless their demands were met. The potential loss to Kroger was enough to get an otherwise unfriendly manager to agree to hear the modest employee demands, and it was Jimmy Hoffa led the negotiations.

Having secured a commitment for a meeting to work out a contract, the workers went back to the loading dock and resumed work, saving the strawberries before they spoiled. It was the beginning of a short-lived but real victory. The end result would be a temporary contract with Kroger for better terms of employment.

Having led this successful strike, Hoffa continued to distinguish himself as a fighter for workers, something for which future Teamsters would revere him. Some of the “Strawberry Boys,” as the striking Kroger workers were called, even remained in Hoffa’s inner circle throughout his career that was now just beginning.

The International Brotherhood of Teamsters

The next step for Jimmy Hoffa was joining forces with an established union in order to effect long-term change. By the 1930s, the International Brotherhood of Teamsters had been around for decades and were a minor but recognized force. When the union’s precursor organizations formed in the 1890s, its members literally drove teams of horses pulling a cart full of goods.

The name Teamsters remained as the shipping industry rapidly modernized in the wake of mass production of cars and trucks and the workers who loaded trucks fell under its jurisdiction; so, the Strawberry Boys sought admission to the Teamsters.

The union not only admitted the Kroger workers; they recognized Hoffa’s extraordinary potential as a grassroots activist and offered him a job as an organizer signing up new members to the Teamsters among the Detroit area’s truck drivers and allied workers.

At that point, the Teamsters primarily represented short-haul drivers. Intercity, long-haul trucking was originally considered something of a different business, but that would soon change. Not coincidentally, Hoffa’s early years with the Teamsters would see its previously stalled membership numbers skyrocket into the hundreds of thousands.

A large part of recruitment involved approaching individual drivers, which wasn’t easy. Hoffa’s method often took advantage of the fact that long haul drivers would sleep in their cabs by the side of the road. He’d knock on the door to wake up his prospect, deliver a rapid-fire introduction, and then duck.

This was because a typical response from such a trucker was a reflexive swing of a tire iron because these drivers faced, among other challenges, a well-founded fear of robbery. Even after they realized the man approaching their cab was no threat, these truckers weren’t likely to warm up much once Hoffa’s initial sales pitch actually began. Union organizing was still quite a radical activity at the time but he’d prevail upon them to just hear him out. His genuine passion eventually won them over.

But if there was danger in the one-on-one interactions, the truly brutal part of the job came on the picket lines. Strikers and strikebreakers traded blows with bare fists, bats, and pipes. Jimmy Hoffa was, from the start, opposed to carrying a gun out of principle. Mob goons hired by businesses to break up strikes (in the early days, union men and gangsters actually weren’t aligned in the ways that they’d come to be at all) weren’t known for scruples on that count, but company managers didn’t necessarily want to order an out-and-out slaughter either.

Owners wanted the Mafia foot soldiers to cause just enough injury to the workers on the front lines to break them up and let non-union replacement workers — “scabs” in labor parlance — through the picket lines. Hopefully, they could even break the spirit of the strikers and get them back to work.

Like the other Teamsters — as well as members of the United Auto Workers and other unions of the day — Hoffa fought hard in the most visceral and physical sense of the word and the muscular, five-foot-five organizer suffered dozens of injuries during his days on the front lines.

Unions Divided In Great Depression America

Jimmy Hoffa’s formal education ended at about the ninth grade — or maybe earlier; he gave contradictory accounts — but he received a master course in union organizing when his boss took him to help with the innovative tactics of Farrell Dobbs, the avowed-Trotskyite leader of the Minneapolis Local of the Teamsters.

By alternating strikes against shipping companies and the retailers and other shipping recipients, Dobbs’ Local broke through otherwise recalcitrant corporate opponents. Later, Dobbs realized that he could scale that kind of tactic up to the whole region by forcing concessions from Chicago companies since most of the biggest companies in America had to either do business in Chicago or trade with companies that did.

Communists were rare among Teamsters leadership, but the success of Dobbs and his allies led the national organization — then based in Indianapolis — to overlook his more radical views. Ultimately though, as the union sought greater influence in national politics, the long-serving Teamsters President Daniel Tobin decided that Dobbs had to go.

Jimmy Hoffa was part of the muscle that launched the coup in the Minneapolis Local, but he would continue to employ the strategies he learned from Dobbs, the leader he helped to oust, ideology notwithstanding.

Harris & Ewing/Library of CongressJohn L. Lewis, head of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), attempted to establish a CIO-affiliated union for the transportation and warehousing industry to compete with the Teamsters, and the conflict between the two unions would often turn violent.

Back in Detroit, the union turf battles continued, with almost as much ferocity as those against the employers. Organizer John L. Lewis had recently split off a faction from the coalition of unions called the American Federation of Labor (AFL), to which the Teamsters belonged, to form a rival umbrella group, the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). Lewis placed his brother Denny at the head of a new union for truck drivers under the CIO aegis that would compete with the Teamsters.

In the violence that ensued, Hoffa reached out to a connection he’d made through a former girlfriend, Sylvia Pagano. Following her relationship with Jimmy, she married Frank O’Brien, who worked as a chauffeur for a mob boss in Kansas City. Frank died shortly thereafter, but their son, Chuckie O’Brien, would become a central player in the Hoffa saga.

Moving back to Detroit, Sylvia began a relationship with the gangster Frank Coppola, Chuckie’s godfather, and Coppola opened a new world of possibilities for the Teamsters. In a parallel to legitimate industry and labor in the Depression-era U.S., North American gangsters, including Lucky Luciano, Frank Costello, and other famous Mafia figures, had recently reached a consensus over regional jurisdictions, forming a National Crime Syndicate with its own governing body and “laws.”

With mob muscle behind them, the Detroit Teamsters Local 299 and their allies drove the CIO-backed drivers’ union out of town. Hoffa’s ability to forge a vast number of ties with stakeholders all over the political and legal spectrum would remain a key to his success — while it lasted.

Power And Public Scrutiny

In 1937, Jimmy Hoffa ascended to the presidency of Detroit Local 299, a post he would continue to hold even after assuming leadership over all of Detroit’s local chapters — and eventually the entire union. The increasingly powerful labor leader then received a draft deferment during World War II, based on the argument that he would be more valuable to the war effort stateside, helping to ensure the smooth running of the transportation sector.

Much of Hoffa’s reputation within the Teamsters came was built during these years before he even became the national union president. In the late 1940s, no longer involved in street brawls, Hoffa was well-positioned to exercise influence in the booming postwar Detroit economy.

As in the manufacturing sector, unionized truck drivers continued to see significant wage increases. In addition to helping to negotiate better pay, Hoffa led the formation of a union health and welfare fund, and what would grow to be a massive pension fund for Teamsters in the Central States region.

In 1952, Hoffa became one of the Teamsters’ national vice presidents, under the newly elected Dave Beck. There were other vice presidents, but Hoffa was second-in-command. When the union moved its headquarters to Washington, D.C. around this time, Hoffa took up part-time residence in the capital. Out of necessity, he soon became entrusted with executive authority over union business once Beck found himself in serious legal difficulties. Beck’s troubles would only be a warm-up for Hoffa’s own.

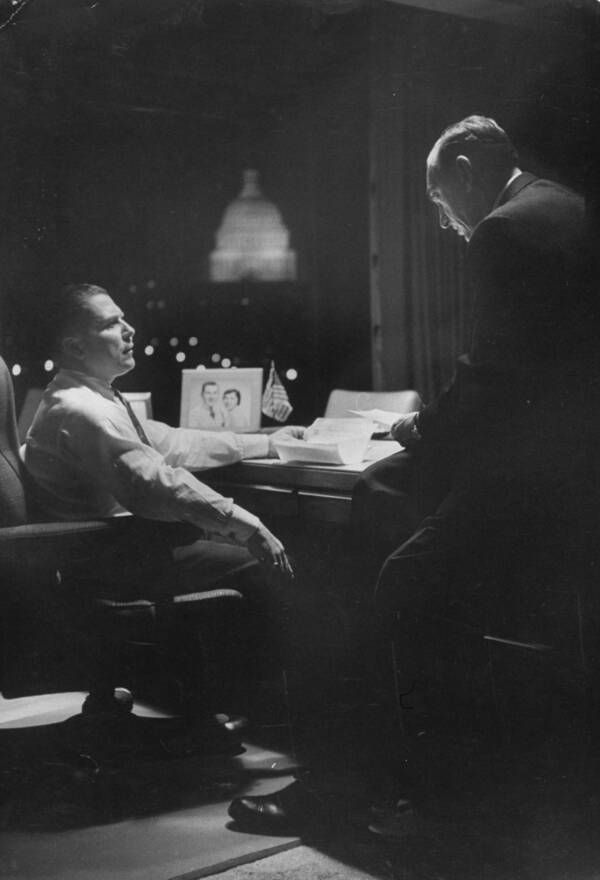

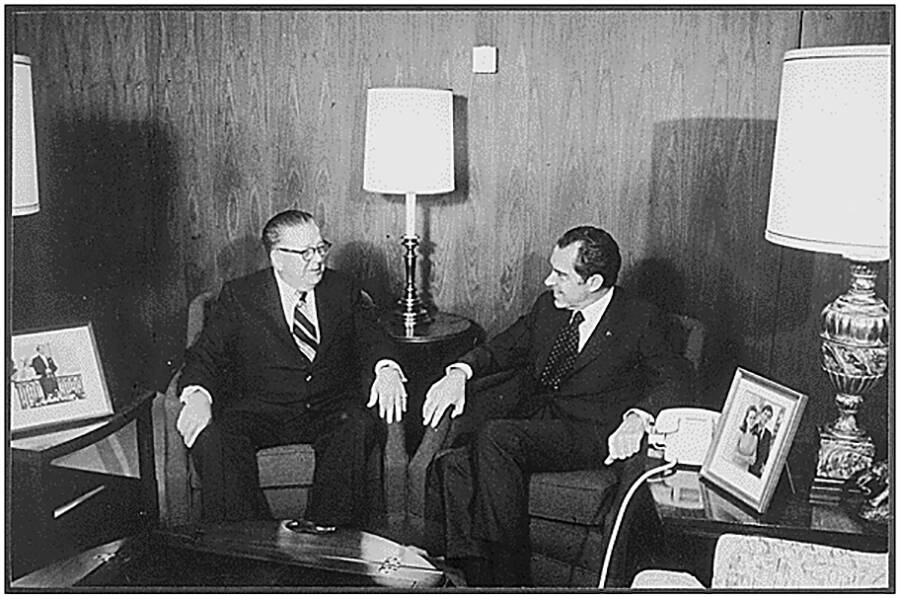

Hank Walker/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty ImagesTeamsters Union President James R. Hoffa talking with Harold Gibbons in his office.

Possibly as a result of tips leaked by Hoffa, Beck came to the attention of a committee on union corruption headed by Senator John McClellan of Arkansas. With hearings primarily conducted by the panel’s hired counsel, Robert F. Kennedy, whose older brother, then-Senator John F. Kennedy sat on the committee, the findings formed the basis of new regulations on the nation’s labor unions.

Beck didn’t fare well before the committee, developing notoriety at the hearings in 1957 for the number of times he invoked his Fifth-Amendment protection against self-incrimination. Beck’s national career was effectively finished, although it would be a few years before a criminal case put him behind bars. The hearings also prompted the AFL-CIO — the two labor organizations reconciled and merged in 1955 — to vote four-to-one to expel the Teamsters from the organization.

The Robert Kennedy-Jimmy Hoffa Vendetta Begins

Ironically, Jimmy Hoffa, whose succession to the office of Teamsters president was a foregone conclusion, could have billed himself as something of an anti-corruption reformer, but that didn’t stick. When Hoffa came before the McClellan Committee, Robert Kennedy developed a fixation on uncovering the new Teamsters head’s collusion with organized crime.

Jimmy Hoffa, for his part, came to despise both Kennedy brothers, viewing them as not only the spoiled children of privilege but hypocrites, since their family fortune came from their father’s bootlegging operation during Prohibition. He railed against Robert Kennedy as someone who represented the opposite of a working man like himself.

The fact that Kennedy had been a football star at Harvard particularly rankled Hoffa. In reality, the two were by this point both white-collar workaholics, not quite mirror images, but evenly matched.

According to one anecdote, Kennedy began driving home from his office on Capitol Hill late one night, saw the lights on in Hoffa’s office at the Teamster headquarters, and turned around to go back to work so that he wouldn’t be outworked by his opponent. Little did Kennedy know, the story says, that Hoffa had begun leaving his office lights on when he went home just to fool Kennedy.

At times, the hearings took on the quality of harsh interrogation. Kennedy, unable to get any meaningful admissions from Hoffa, fell into ad hominem attacks, prompting righteous speeches by the labor leader in his own defense.

The example of Beck showed the negative publicity you could get by asserting fifth amendment protections, so Hoffa was careful to avoid explicitly doing so. Hoffa instead claimed poor memory or — in what became an exasperating process for the committee — referred difficult questions to an associate who would then assert their fifth amendment rights against self-incrimination.

These televised hearings were watched by an estimated 1.2 million viewers, a massive figure for 1957. This made Jimmy Hoffa a household name and a hero among working-class people who enjoyed watching a union man run circles around elite politicians.

In public comments, he portrayed his testimony as the defense of the Teamsters Union against slander, and much of his membership viewed him as he hoped. A criminal investigation against Hoffa became, in his telling, a witch hunt against the Teamsters in general and an attack on union workers everywhere.

Bettmann/Getty ImagesRobert Kennedy speaks with labor leader Jimmy Hoffa. Kennedy was chief counsel for the Senate Rackets Committee and investigated Hoffa’s ties to organized crime.

One of the members of the McClellan Committee was Sen. Joseph P. McCarthy of Wisconsin, and Robert Kennedy had served as a minor counsel on McCarthy’s infamous anti-Communist hearings. So for the American people, the accusation that the same politicians were launching another witchhunt — this time against labor unions — wasn’t so far-fetched. And it’s no exaggeration to say that many people saw Robert Kennedy as obsessed, even as considerable evidence showed that Jimmy Hoffa was guilty of corruption.

In fact, things looked so incriminating for Hoffa that Kennedy vowed to jump off the Capitol dome if Hoffa wasn’t convicted. At issue was not just the people Hoffa associated with, but what their business dealings were, as well as how Hoffa managed the union funds at his disposal.

Despite Kennedy’s premature boast, however, the hearings would end without a conclusion on either matter, though both issues would continue to dog Hoffa who was just now beginning his tenure as Teamsters president.

The Fiery Labor Leader In Stormy Times

Bettmann/Getty ImagesJames R. Hoffa, Detroit Teamsters leader, shown with his family. Left to right: son James, 15, daughter Barbara Ann, 18 and his wife, Josephine.

If he had escaped legal scrutiny, life would have been good in those days as Teamsters president in the late ’50s and early ’60s.

Jimmy Hoffa always maintained that family came before work, even though his punishing schedule and long workdays may not have reflected that belief. Nevertheless, he’d met and instantly fallen for Josephine Poszywak back in the 1930s when she was picketing the laundry company she was working for, which, though non-union, was potentially within the Teamsters’ jurisdiction.

The two married less than a year later, and soon had two children, James P. and Barbara. They lived in a modest middle-class home on Detroit’s West Side, although they also owned a summer cottage north of the city and a primitive hunting lodge farther north where the Hoffas enjoyed hosting family and friends.

NetflixJimmy Hoffa — played by Al Pacino in Martin Scorsese’s film The Irishman (above) — tried to balance his family life with his punishing schedule.

By most accounts, Jimmy Hoffa was an exceptionally generous host, which is in keeping with the generosity he displayed in other areas of his life. He didn’t spend much on himself, even downgrading the model of car he drove from Cadillac to Pontiac once he rose to leadership. Meanwhile, Jimmy and Josephine Hoffa remained truly in love, and the violent, curse-word-laced temper he could exhibit in his professional life was never on display at home, where swearing was forbidden.

One unusual facet of their home life, however, began when Hoffa’s former sweetheart, the twice-widowed Sylvia Pagano, came to live with the Hoffa family. Her son, Charles “Chuckie” O’Brien became something of an older brother to the Hoffa children, and Jimmy Hoffa treated Chuckie very much like a son. Some have speculated that Hoffa, not Frank O’Brien, was Chuckie’s actual father, but that claim has never been substantiated. If true, the Hoffa marriage survived any controversy, and Pagano and Josephine Hoffa became close friends.

While Hoffa held on to normalcy at home, his controversy-laden presidency of the Teamsters was pushing the union to new heights.

Victory And The Self-Destruction Of Jimmy Hoffa

NetflixAl Pacino as Jimmy Hoffa in The Irishman.

The Teamsters didn’t align with the Democratic Party the way most organized labor did in the 1960s, and — in large part due to Jimmy Hoffa’s very public battles with Robert Kennedy — there was no way they were going to endorse John F. Kennedy for president in 1960. Hoffa instead developed a working relationship with Richard Nixon, then vice president under Eisenhower, and the Republican nominee for president in 1960.

Unfortunately for Hoffa, Kennedy won the election and took office in 1961 then made the very controversial move of appointing his brother attorney general. If Robert Kennedy was obsessed with Hoffa before, now that obsession had real bite to it, putting Jimmy Hoffa in the crosshairs of the U.S. Department of Justice. Robert Kennedy hadn’t given up his goal of locking Hoffa up; quite the contrary, he created what he nicknamed the “Get Hoffa Squad.”

Despite the antagonism from the Kennedys in Washington, Hoffa continued to build the Teamsters, growing it to nearly 2 million members, meaning that union accounts were flush with funds. Hoffa wanted to keep pushing into new and unorganized industries and he was coming close to achieving what he considered his life’s work: the adoption of a standard national contract for all truck drivers, which would virtually lock in the gains made by labor.

“Jimmy Hoffa has put more bread and butter on the tables for American kids than all his detractors put together.”

Jimmy Hoffa was respected by his opponents at the bargaining table as much as his allies. He could be a hard, even histrionic, bargainer when he knew he could exact a concession from management, but he was fundamentally after an agreement; he wouldn’t push for gains he judged to be out of reach. The fact that he was almost certainly giving kickbacks and lowball contracts to companies at his discretion probably also won him admirers in businesses both above-board and illicit.

The culmination of Hoffa’s work would be the 1964 National Master Freight Agreement which brought more than 400,000 long-haul drivers under a single union contract. Congressman Elmer Holland, a Democrat from Pennsylvania, said at the time that “Jimmy Hoffa has put more bread and butter on the tables for American kids than all his detractors put together.”

Unfortunately for Hoffa though, much of his time was being dedicated to his own legal defense. He evaded the law for a few years, but a combination of miscalculations and paranoia eventually led to his prosecution.

NetflixAl Pacino as Jimmy Hoffa (center) and Robert De Niro as Frank Sheeran (adjacent, near right) in The Irishman.

Hoffa, along with some other investors, bought up some marginal real estate in Florida and began selling it as an idyllic retirement option for union members. But the pricing was significantly marked up and Hoffa was shown to have used funds from the Teamsters pension fund to secure loans from a Florida bank for the real estate project.

Hoffa tried to insulate himself from the charges by attempting to divest himself of the landholdings, but to do so required creative accounting elsewhere, which only raised more red flags for prosecutors and, ultimately, jurors.

Earlier, Hoffa and a fellow Teamster official had set up a trucking company and registered it in their wives’ names to avoid the obvious conflict of interest. Colluding with a customer, Hoffa then secured a no-bid contract for his company to deliver new cars to dealerships.

Jimmy Hoffa also began loaning money from the Teamsters’ Central States pension fund to Mafia bosses to build Las Vegas casinos. This was possible only because he had reorganized the structure of the fund’s board of directors to essentially give him executive authority over investment decisions.

The shell trucking company was incorporated in Tennessee, and so it would be in Nashville that the end would begin for Hoffa. Charged in federal court for the scheme, Hoffa set about bribing several jurors, using intermediaries to deliver the payments. With even a single juror in his pocket, he could guarantee a hung jury, and thus a mistrial, giving him time to come up with a plan for how to continue evading criminal charges.

But he wasn’t able to outrun trouble for much longer.

The Downfall Of Jimmy Hoffa

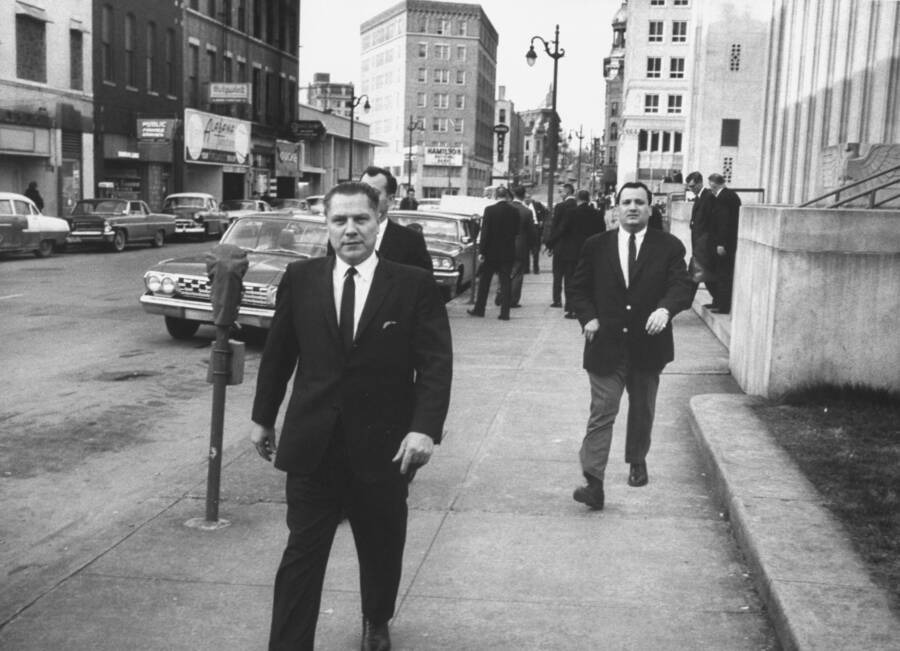

Robert W. Kelley/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty ImagesTeamsters boss James R. Hoffa leaves a Federal Courthouse after a trial for jury tampering.

Jimmy Hoffa’s legal trouble reached new heights when a Teamster associate who he had trusted with knowledge of the scheme began cooperating with federal prosecutors. Guaranteed anonymity, he testified about the jury tampering and the frustrated Get Hoffa contingent suddenly had a very solid case. The new trial took place down the road in Chattanooga, a venue supposedly less familiar with the first trial.

Here, there was no question about the outcome. The second jury found Hoffa guilty of tampering with the first, a much more serious offense than the original case.

And so, in 1964, Hoffa received a sentence of five years. Appeals began right away, but by 1967, all hope was exhausted, and following a final speech decrying the unfairness of his plight, James R. Hoffa turned himself over to state custody and was incarcerated at Lewisburg Federal Penitentiary. Along the way, Hoffa actually racked up a second conviction, this time for the misuse of pension funds, and so he was now looking at a possible 20-year sentence.

Throughout this era, several prominent gangsters, corrupt Teamster leaders, and gangsters who were also corrupt Teamster leaders ended up going to prison, so it’s not surprising that Jimmy Hoffa would know some of his fellow inmates.

One such inmate, Anthony “Tony Pro” Provenzano was a trusted loyalist and a captain in the Genovese crime family, but, for reasons that may have had to do with Hoffa’s maneuvering toward a rival Mafia faction, the two had a falling out and Provenzano developed a fateful grudge.

Meanwhile, Lewisburg wasn’t the worst prison in the world, but it was overcrowded and the food tasted like punishment. That and a conscientious exercise regimen helped Hoffa drop some of the weight he’d put on in his middle years and he actually staved off early-stage diabetes.

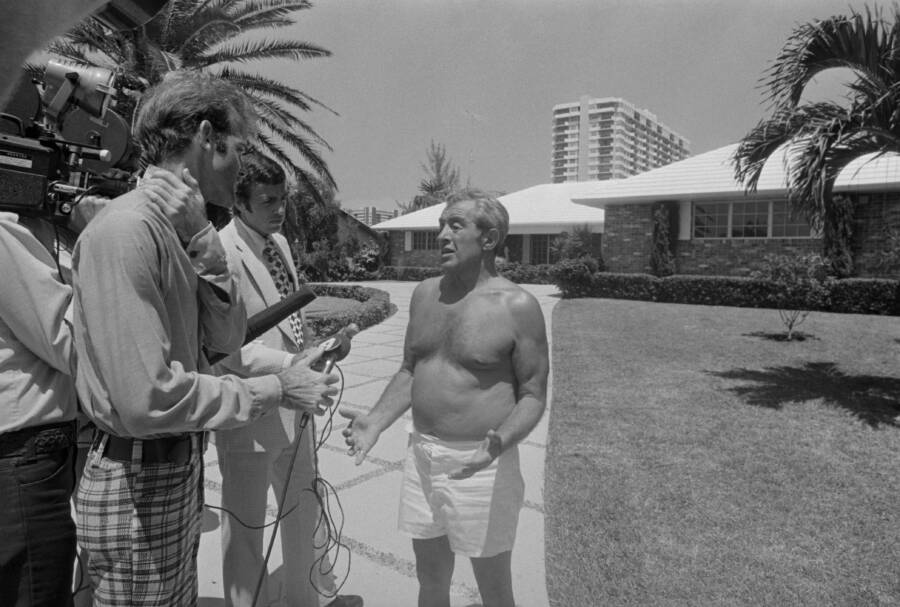

Bettmann/Getty ImagesAnthony “Tony Pro” Provenzano gestures with his hands as he meets with newsmen outside his home. It is believed Hoffa was on his way to a luncheon with Provenzano when he disappeared.

His daughter Barbara sent him a steady supply of books to read, which was a departure for a man who had once declared, “I don’t read books. I read labor agreements.” For the first time since he began his labor activism, Hoffa had time to augment his remarkable practical understanding of labor relations with a study of the early history of the union movement.

At the same time, he was a dutiful prison worker and carried out his work detail of stuffing mattresses without complaint and never had any known issues with prison staff. Even with his exemplary behavior, though, he was still twice denied parole.

To get a sense of the admiration the Teamsters membership had for Hoffa, one only need to look at Hoffa’s re-election as president of the Teamsters in 1968 while he was still in prison. It wasn’t so much that Teamsters thought Hoffa was innocent — he was very obviously guilty — but for the rank-and-file Teamsters, everyone in power was just as guilty as Hoffa, if not more so.

Unlike Hoffa, however, the corruption of politicians and businesses came at the expense of working people, while Hoffa’s corruption could be framed as an acceptable compensation for the material benefits that he was able to secure for the union membership. He may have been a crook, but he shared the wealth and fought hard for the men and women who others had been leaving behind.

Wikimedia CommonsTeamsters acting president Frank Fitzsimmons is thought to have solicited a commutation of Jimmy Hoffa’s prison sentence from president Richard Nixon in 1971 — with the stipulation that Hoffa could not return to a leadership position in any union until 1980.

Though he was re-elected, Jimmy Hoffa was obviously in no position to carry out the day-to-day work of managing one of the largest labor organizations in the world, so he appointed Frank Fitzsimmons, a trusted ally, to serve as acting president in his absence just before he began serving his prison sentence.

Fitzsimmons swore to run the Teamsters as Hoffa’s proxy and to hand the top spot back to him as soon as his longtime friend was free, but Fitzsimmons soon swerved in a different direction.

Hoffa’s regime was characterized by highly centralized authority — that is, he and he alone controlled everything possible. In an earlier era, however, the Teamsters had been much more of a federation of autonomous regional entities and Fitzsimmons — a less skilled leader than Hoffa, either by preference or weakness — returned much of the power in the union to the leadership of the Locals.

While this might sound laudable, in practice this simply gave corrupt Local bosses a freer hand — and those Local bosses had bosses of another sort themselves. A regional Mafia boss was in a much better position to assert control over a smaller Local than if that same boss had to pressure a national leader of Jimmy Hoffa’s caliber, so whether he knew it or not, Fitzsimmons effectively turned the Teamsters over to the mob.

To highlight the essential contrast between the two leaders, all one needs to know is that under Fitzsimmons, a particularly odious scheme was being run by Teamsters that involved sending a team of thugs to strongarm area businesses — not to allow workers to organize, but rather to extract “protection” payments that would allow the company to remain non-union. Hoffa would never have countenanced such a betrayal of the cause.

The King In Exile

Fitzsimmons ultimately managed to work out a quid pro quo that he likely believed would sideline Hoffa forever and allow him to remain at the top of the Teamsters Union.

The Teamsters, who hadn’t endorsed Nixon in 1968, would do so in 1972, along with a contribution to the Committee to Re-Elect the President (CREEP) — one that may have been as high as $1 million. Nixon just had to commute Jimmy Hoffa’s sentence with the stipulation that Hoffa must “…not engage in direct or indirect management of any labor organization” until 1980, the year his prison sentence would have ended.

In December 1971, Hoffa received the commutation, left prison, and flew to Michigan to reunite with his family. It didn’t take long apparently for Hoffa to learn that he was barred from union leadership and was reportedly furious when he found out the conditions of his release. He felt that he was almost done with the original five-year sentence and that he stood a good chance of winning parole with no restrictions long before 1980.

He tried to sue the government to get the restriction lifted, and began working out a pathway to regaining power, starting from the bottom as a low-level staffer at the Detroit Local 299.

This, in theory, would all but guarantee him the presidency of the Detroit Local in the next election and put him in a position to win back his old position in the national Teamsters election set for 1976. Following Nixon’s resignation in 1974, Hoffa felt especially optimistic that fellow Michigander Gerald Ford would lift the restrictions on his commutation.

It was not to be, however. In 1974, a U.S. District Court in Washington, D.C. ruled that the stipulations placed on Hoffa’s commutation were within the powers of the presidency and that they were appropriate given that Hoffa’s crimes were tied to his leadership of the Teamsters.

Meanwhile, Fitzsimmons’ Mafia allies were quite happy having their new, more pliable friend in the presidency of the Teamsters and had no interest in seeing the domineering Hoffa return to power. Moreover, they feared that a resurgent Hoffa might tip the balance of power among feuding families, something that might even threaten to become a nationwide mob war. Russell Bufalino, the “Silent Don” who headed up the Philadelphia Mafia, more than once tried to get a message to Hoffa to back off.

Rather than being discouraged, the pushback enraged Hoffa, who soon began threatening to expose Fitzsimmons’ mob connections — which would put a lot of powerful people under an uncomfortable national spotlight.

It also would have undoubtedly incriminated Hoffa himself, if he was serious about the threats, but Hoffa apparently overplayed his hand. And so, by late 1974 — though the stories are widely disputed and the truth may never be known for sure — Bufalino reportedly authorized a hit on Hoffa, with Anthony Provenzano in charge of carrying it out.

The Final Hours Of Jimmy Hoffa

Bettmann/Getty ImagesThe Machus Red Fox in Bloomfield Township, Michigan — Jimmy Hoffa’s last known whereabouts, photographed two days after his disappearance.

In July 1975, Jimmy Hoffa received an invitation — through an intermediary, Detroit mobster Anthony “Tony Jack” Giacalone — to a sit-down meeting with Provenzano to work out their differences. Hoffa almost certainly suspected that he was in danger.

According to Frank “The Irishman” Sheeran — a longtime friend of Hoffa’s, the head of a Teamsters local in Delaware, and an alleged part-time hitman — Hoffa raised the idea of Sheeran’s sitting in on the meeting for protection.

A note written by Hoffa, later found by investigators at Hoffa’s Lake Orion vacation home, indicates a meeting at 2:00 p.m. on July 30 at the Machus Red Fox, a restaurant in the Detroit suburb of Bloomfield Township. The intention appears to have been to just use the parking lot as a rendezvous point before proceeding to some other, confidential meeting site.

En route from his lake house in Lake Orion, Hoffa tried to connect with another associate, Louis Linteau, who also might have been helpful for protection. It turned out that Linteau was away from his office for lunch, however, so Hoffa continued on to the meet-up point alone.

Having arrived at the Machus Red Fox, Hoffa went to a payphone and called his wife at 2:15, upset that Giacalone and Provenzano were keeping him waiting. He told her he’d be back up at Lake Orion by 4:00. The meeting time had come and gone, and still, no one showed.

Hoffa went into the restaurant, ate lunch, came back out, kept waiting, and eventually went back inside the Red Fox and made a phone call to Linteau from a payphone in the basement.

After that, Jimmy Hoffa was never seen or heard from again.

Death And Rumors Behind Jimmy Hoffa’s Disappearance

paul bica/FlickrOne urban myth claims that Jimmy Hoffa’s remains were buried beneath the Renaissance Center in downtown Detroit.

When Jimmy Hoffa failed to return that evening, his wife began to panic. The next morning, she called her children and told them that their father never come home. Barbara, who was living in St. Louis, Michigan at the time, immediately got on a plane and flew to Detroit.

On the way, she was hit — by her own account — with an uncanny sureness that her father had been murdered, even down to the clothes he was wearing the moment he was killed. By that evening, an investigation involving the Michigan State Police was underway with the FBI joining the search for Jimmy Hoffa soon thereafter.

For a time, the family held out hope that the disappearance might have been a kidnapping for ransom or a scare tactic. But investigators were fairly sure early on that they were dealing with a murder. An exhaustive search for Hoffa’s body began — a search that continues to this day, both officially and unofficially.

Among the more outlandish but persistent myths about Jimmy Hoffa’s disappearance is that he was buried underneath Giants Stadium in New Jersey, which was being built at the time of his disappearance, given that the involvement of the New Jersey mob in his murder isn’t at all far-fetched. The story has even outlived the stadium itself, which was torn down in 2010. No human remains were found at the site.

Other mob informants also suggested that Hoffa’s body was transported to New Jersey, with the disposal site being a certain landfill believed to be a popular hiding place for bodies. However, a subsequent search by investigators turned up no trace of Jimmy Hoffa.

Yet another tale has Hoffa being buried in a shallow grave near the murder site, with the killers intending to go back later to move the body but for various reasons never being able to do so. One of the more outlandish stories has Hoffa’s body crushed inside a car compacted for scrap metal for shipment to Japan.

The FBI dedicated considerable resources to investigating Jimmy Hoffa’s disappearance and gathered substantial evidence, but there was never a conclusive-enough case to charge anyone with the crime. Without a body, authorities held out for several years before finally declaring Jimmy Hoffa dead in 1982. His murder case remains open and is likely never to be solved.

Rough Sketch Of A Crime Scene

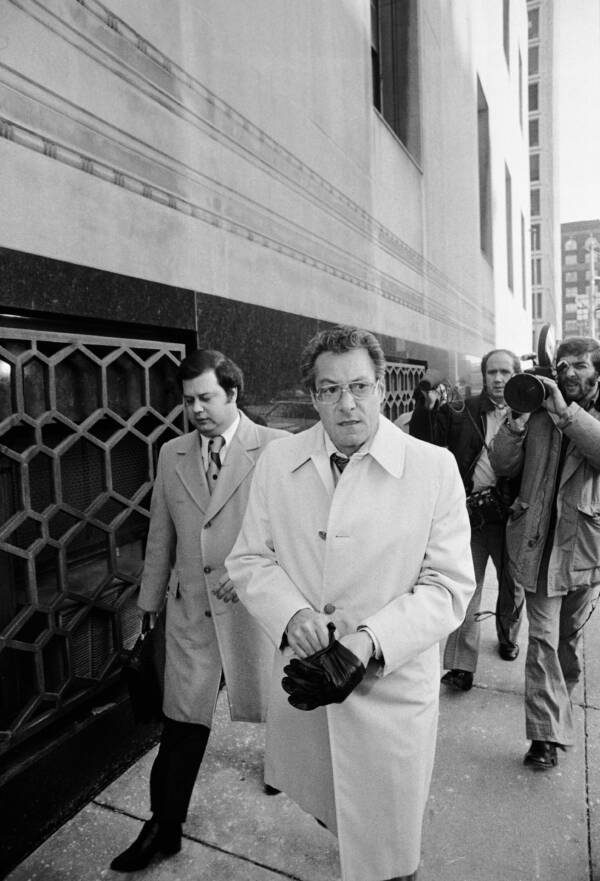

Bettmann/Getty ImagesSalvatore Briguglio, of Paramus, New Jersey, leaves the Federal Courthouse after appearing before the Grand Jury investigating the disappearance of former Teamsters boss James R. Hoffa. Briguglio is the business agent for Teamsters Local 560 and a longtime associate of Anthony “Tony Pro” Provenzano. Briguglio (right) along with three other New Jersey residents were called to testify on the disappearance of Hoffa.

Dan Moldea, author of The Hoffa Wars — one of the first biographies of Jimmy Hoffa following his murder — spoke with many people connected to Jimmy Hoffa, including some who may have had a role in his killing. Among them is Sheeran, the focus of Martin Scorsese’s film The Irishman, which is based on Sheeran’s “confession” to former prosecutor Charles Brandt for his 2004 book I Heard You Paint Houses.

Many people familiar with the life and times of Sheeran doubt his reliability, especially his claim to have been the actual executioner, but Moldea considers the basic outline of Sheeran’s account plausible, even if he greatly exaggerated his role in the events.

According to Moldea, sometime after 3:30 p.m. on July 30, Chuckie O’Brien showed up in the parking lot of the Machus Red Fox, driving a borrowed maroon Mercury Marquis with Salvatore Briguglio as a passenger. Moldea believes that Briguglio was Jimmy Hoffa’s killer, but since Briguglio was murdered in 1978, just three years after Hoffa disappeared, charges were never brought against him.

Moldea believes that O’Brien was likely unaware of the murder plot and was used by the mob hitman to get close to Hoffa. Although O’Brien’s relationship with Hoffa had become strained, and he had worked to ingratiate himself with Fitzsimmons, it is much more plausible that O’Brien really was just a driver. In a mob hit, sending someone the target trusts is typically done to get them to let their guard down and get into a car so they can be taken to an out-of-the-way murder site.

The car in question did turn out to contain a single hair from Jimmy Hoffa, a DNA test eventually proved, but O’Brien maintained that he had nothing to do with the murder of Hoffa and since there was no way to determine when Hoffa’s hair was left in the car, there wasn’t anything that investigators could charge O’Brien with.

Moldea also found it believable that Sheeran was in the car as well, though how much he knew of the plot is debatable. The list of likely suspects includes several corrupt Teamster officials with mob ties, like Thomas Andretta, an associate in the New Jersey Mafia, but nobody really believes that Sheeran was ever on that list.

NetflixFrank Sheeran, played by Robert De Niro in the film The Irishman, claims to have been the one who killed Jimmy Hoffa, but there is considerable reason to doubt his “confession.”

Still, Sheeran’s confession is out there, and in his account of Jimmy Hoffa’s murder, he gives a specific address on Detroit’s West Side where he claims he shot and killed him. But even though a forensic examination of the house turned up evidence of blood, later testing proved that it wasn’t Hoffa’s blood.

If the exact location Sheeran gave is bogus and the story is fabricated, however, the general idea of the hit taking place in a private home would still be likely. Hoffa would be expecting to go to a confidential meeting, not one in a public space where law enforcement could observe it and possibly listen in.

Sheeran claims that Jimmy Hoffa’s body was disposed of in a nearby garbage incineration facility, but as Moldea noted, the FBI ruled out that location early on in the investigation. The fact that it burned to the ground shortly after investigators visited it adds intrigue to the story, but the facility was literally full of industrial incinerators; it didn’t need the mob to burn it to the ground, it could have done that all on its own as long as someone working there simply got careless.

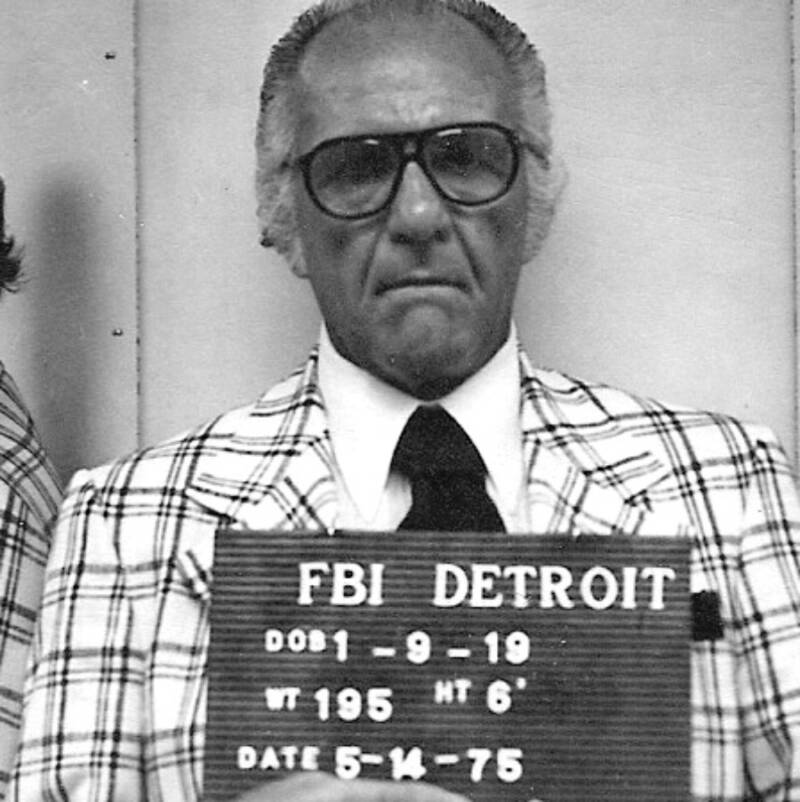

Wikimedia CommonsAnthony Giacalone, a member of the Detroit Partnership Mafia organization in a 1975 mugshot. Giacalone is one of the Detroit mobsters the FBI investigated in connection with Hoffa’s disappearance.

That said, some nearby cremation site is plausible. If the point is to destroy evidence, there’s little to be gained by shipping a body, intact or otherwise, across the country or abroad. Whatever happened to Jimmy Hoffa’s body, it almost certainly didn’t travel very far from the site of his murder, and cremation leaves little if anything behind that can be identified.

As for Provenzano, who Moldea believed arranged the murder with Giacalone, he was careful to establish a solid alibi. Provenzano made sure to be seen by multiple witnesses playing cards with friends in New Jersey on July 30, 1975. Giacalone, meanwhile, was at an Oakland County health club when the purported hit went down. Neither one was ever charged in connection with Jimmy Hoffa’s disappearance, but there is little doubt about their involvement in it.

The Legacy Of The Controversial Labor Leader Today

Jimmy Hoffa, and indeed a wide array of his colleagues in the Teamsters in the mid-to-late 20th century, were highly corrupt, but even knowing Hoffa’s shortcomings, many Teamsters remained loyal — even devoted — to Hoffa and his legacy. To them, the authoritarian organizer may have been a thief, but he was also something of a Robin Hood.

From the earliest days as an organizer, Hoffa learned that the fights that matter are often knock-down, drag-out affairs where fair play and honesty could be a weakness for your enemies to exploit. Hoffa played a corrupt game for sure, but he played for a decidedly different team than the other players of the era.

For millions of working families struggling to get by in this country, Hoffa was their guy in the fight and he beat the powerful at their own game, passing along the winnings to the rank-and-file Teamsters and their families like no other union leader had ever done. And if he took a little cut off the top for himself or his allies, that was fine by his membership: He earned it as far as they were concerned.

The disappearance of Jimmy Hoffa in many ways marked an end to that shared prosperity in America. Starting in the 1970s, union density in the U.S. had been on a steady decline, wages had stagnated, and working families had fallen farther behind than at any time since the Gilded Age and the Great Depression. Even today, while Jimmy Hoffa is a meme or a joke for many people, for union households and working men and women old enough to remember him, Jimmy Hoffa was the last hero of the American labor movement and his loss is keenly felt.

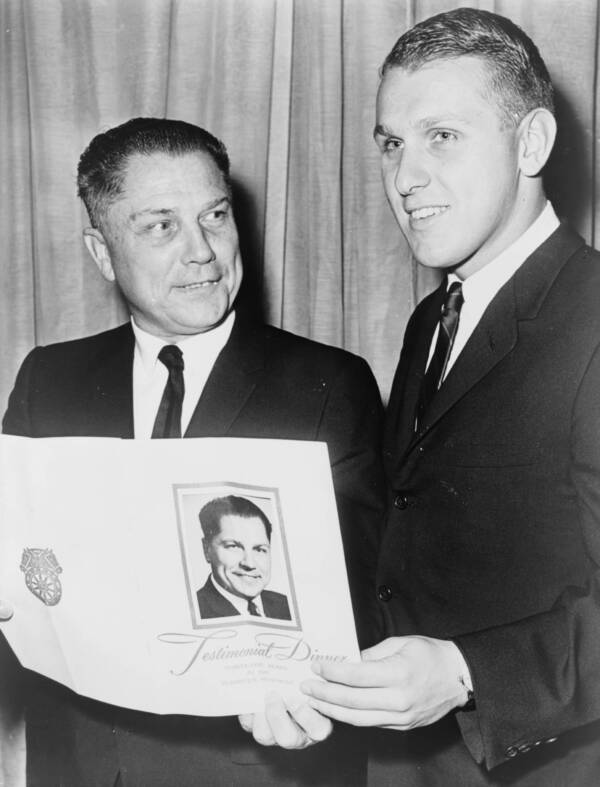

Library Of CongressMany years after this picture of James R. Hoffa and his son, James P. Hoffa (right), the latter would lead the union through a different era.

As for the mobsters who surely killed him, their reckoning would come soon enough. Within a decade and a half, the various Mafia families that Hoffa had to navigate throughout his career began crumbling due to federal prosecution and they became hollow shells of what they once were.

Meanwhile, the Teamsters’ leadership began a campaign of genuine reform. Today, Jimmy Hoffa’s son, James P. Hoffa, heads up the union virtually synonymous with his father’s name and has been at the helm longer than his namesake. Running a campaign for general president of the union on the explicit vow to rid the Teamsters of mob influence, James P. Hoffa told the membership: “The mob killed my father. If you vote for me, they will never come back.”

Now that you’ve read about the life and disappearance of Jimmy Hoffa, check out the most popular theories about Hoffa’s disappearance, including one of the most recent Hoffa theories from 2017.