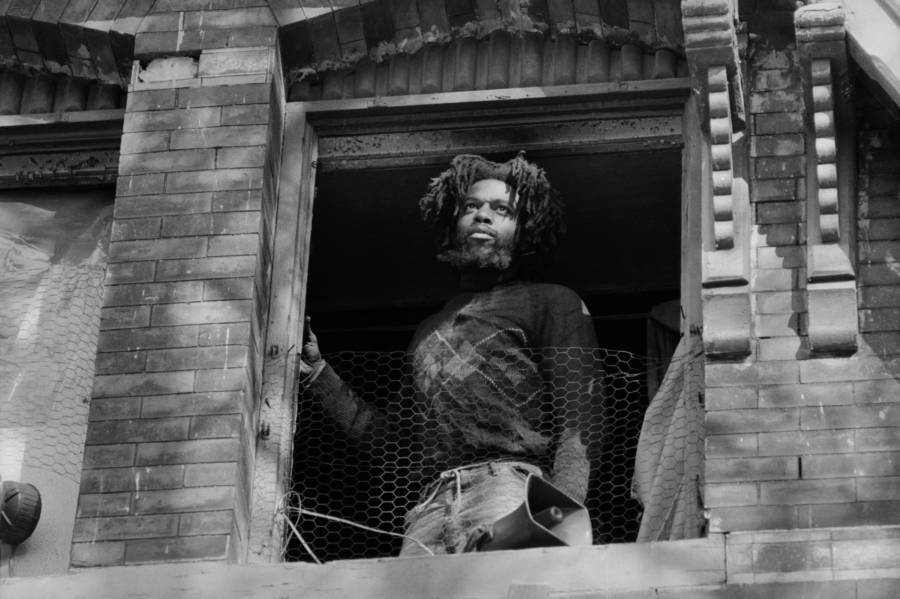

John Africa co-founded the Black activist group MOVE, whose home was bombed by Philadelphia Police in 1985.

MOVEJohn Africa in his recognizable dreadlocks and sunglasses.

The 1985 MOVE bombing remains one of the most egregious police responses in United States history. Frustrated by the militant Black liberation group and its refusal to evacuate their headquarters, the Philadelphia police dropped a bomb on their rowhouse, killing 11 people — including MOVE founder John Africa.

For years prior to the bombing, MOVE was a thorn in the side of the local authorities thanks to their anti-war protests and demonstrations against police brutality. In 1978, MOVE was involved in a standoff that ended with a dead police officer. The 1985 bombing was a clear and vicious response from the Philadelphia police.

In an era where police brutality goes largely unpunished, John Africa’s story remains urgently relevant.

Chronicled in the HBO documentary 40 Years A Prisoner, the horrific police violence against the Black activist group — and the sadly predictable lack of consequences for those in power — has a tragic resonance in a nation still grappling with the police killings of George Floyd, Brianna Taylor, and many others.

But John Africa was more than a martyr in the fight for Black liberation. He left behind a complicated legacy as both a peaceful activist and a cult-like leader who encouraged his followers to stockpile guns and explosives.

The Early Life Of Vincent Leaphart

Born Vincent Leaphart on July 26, 1931, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, John Africa was raised in the Mantua neighborhood of West Philadelphia during the Great Depression.

Testing with an IQ of 79, he didn’t show much promise in school and was functionally illiterate. At age nine, he transferred to a school that taught simple trades to children who were determined to be “slow learners.”

His devoutly religious parents regularly took their nine children to the Metropolitan Baptist Church, until Africa’s mother Lennie Mae abruptly died in her early 40s. While her widowed husband practically fell to pieces, John Africa would later tell MOVE members that the hospital had “killed” her.

At 18, he was drafted by the Army and fought in the Korean War for more than a year before returning home. After a failed marriage, Africa moved into the multicultural Philadelphia neighborhood of Powelton in 1971. The town, which was near the University of Pennsylvania, was a hub of activism that made Africa feel right at home.

Getty Images MOVE members barricading their headquarters amidst escalating tensions in the late 1970s.

Soon afterward, he joined 13 others in signing the 1971 Community Housing Inc. manifesto, which outlined policy changes regarding discrimination against the poor.

A year later, John Africa expounded on his vision and co-founded MOVE with University of Pennsylvania graduate Donald Glassey. At just 24-years-old, Glassey thought he had struck gold for his thesis, which focused on the participation of poor people in the decision-making process of public housing policy.

At first, Glassey had very fond memories of MOVE’s co-founder.

“He was very gentle and seemed to be a warm, loving-type person,” recalled Glassey. “I said, ‘You have some fascinating ideas here, you should write them down.’ And he said, ‘That’s a great idea, but I can’t write very well.’ I said, ‘I can take care of that for you.’ And we started.”

Africa Starts A Movement With MOVE

Leif Skoogfors/CORBIS/Corbis/Getty ImagesMOVE members were encouraged to wear natural hairstyles and eat raw foods.

With Glassey’s prompting, John Africa dictated his views into a 300-page book later known as The Guidelines or The Teachings of John Africa. It took a year for the anti-science and anti-technology manuscript to be complete. But as MOVE grew larger, Glassey recalled Africa becoming more controlling.

“The poison that came out of him — I was shocked,” said Glassey. “Up to that point, I had only seen Vincent in a positive light. He told me that people should work to support him — that’s how he viewed the co-op, that people who were working should work to support others.”

Africa and Glassey moved out the next year and set up shop on Pearl Street, where MOVE began participating in a series of notorious stunts that garnered federal attention.

One incident saw MOVE members handcuff talk-show host Mike Douglas in his studio. An incident in which MOVE members handcuffed and shot a chimpanzee with a tranquilizer dart also enraged an animal rights group. Africa fell out with the housing co-op, as well, and subsequently ordered members to be harassed.

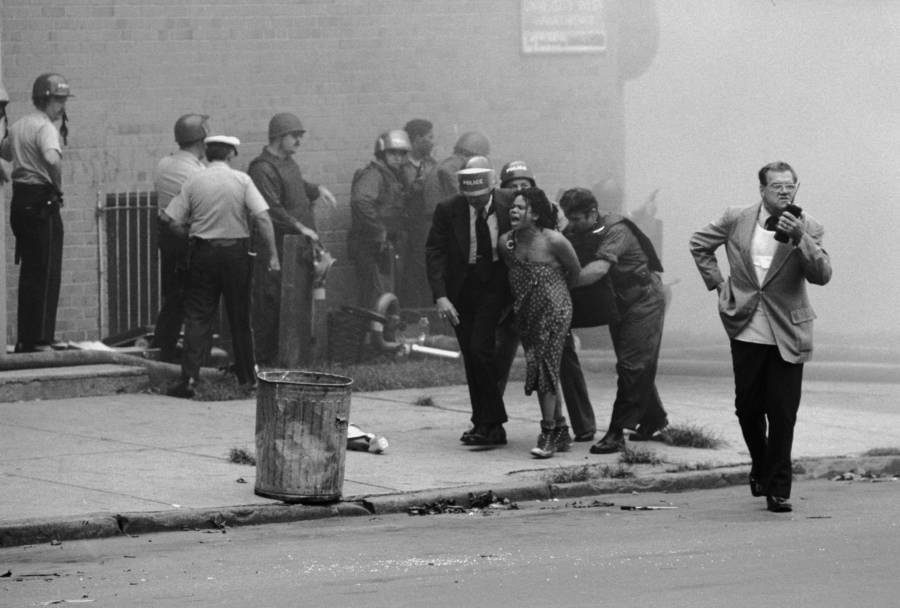

Bettmann/Getty ImagesMoments after the 1985 MOVE bombing.

“Vince was being turned into a godlike figure,” said a local who watched the group’s evolution first-hand. “The transition from Vincent Leaphart to John Africa took probably about a year, a year and a half — until people never knew about Vince Leaphart, they only knew about John Africa.”

The 1985 MOVE Bombing

While actual membership numbers remain unknown, MOVE grew into a sizeable activist group. Everyone lived together and spoke of members as family. The more devout members honored co-founder John Africa by changing their last name to Africa.

Initially, the determined anti-corporation Black liberation group protested at zoos, pet stores, and political rallies. They composted, homeschooled their children, and fed them a diet of raw foods when they weren’t protesting police brutality or the Vietnam War. In 1977, however, things began to devolve as authorities made cracking down on MOVE a priority.

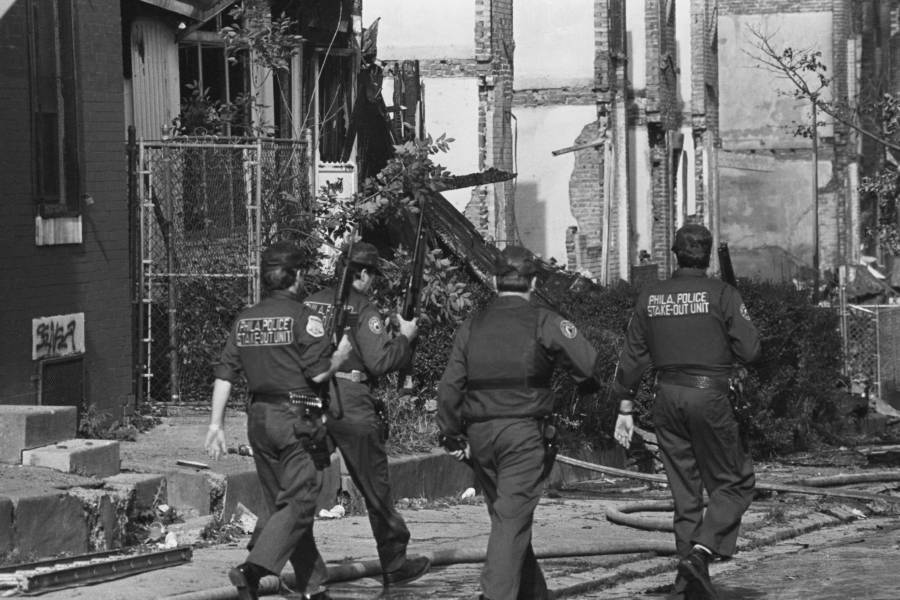

Bettmann/Getty ImagesPolice marching through Powelton one day after the bombing.

“Don’t attempt to enter MOVE headquarters or harm MOVE people unless you want an international incident,” the group declared in a written statement to police. “We are prepared to hit reservoirs, empty hotels, and apartment houses, close factories, and tie up traffic in major cities of Europe.”

Though many sympathized with MOVE’s ethos, others were unnerved by their increasing militance. Then-Mayor Frank Rizzo, who had already developed a negative relationship with Black residents (as was the norm at the time), decided to evict the group from their Pearl Street home in 1978.

By then, the Department of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms had noted that the written MOVE statements included the chemical equation for nitroglycerin — the main ingredient in TNT.

They had also turned Glassey into an informant, who claimed Africa had a “Charles Manson-type grip on MOVE members” and that the group was stockpiling bombs and counter-culture literature such as The Anarchist’s Cookbook.

Leif Skoogfors/CORBIS/Corbis/Getty ImagesAuthorities arresting an unidentified woman near the bombing.

The standoff spanned 15 volatile months, during which armed MOVE members stood guard and prevented strangers from entering. But it all came to a tragic end when one police officer was killed, and nine members of MOVE — known thereafter as the MOVE 9 — were convicted of his murder and sentenced to life in prison.

Despite his lack of education, John Africa represented himself in court on charges related to the standoff. The 1981 appearance saw Africa outsmart a Harvard-trained prosecutor who mistakenly thought the case a slam-dunk. In the end, John Africa was acquitted on all charges.

MOVE then relocated to a quiet, middle-class neighborhood on Osage Street the year after Africa’s acquittal. Their new neighbors complained endlessly about the group, with grievances ranging from trash littering the property and confrontations to loudly broadcast, sometimes obscene, messages blaring from bullhorns.

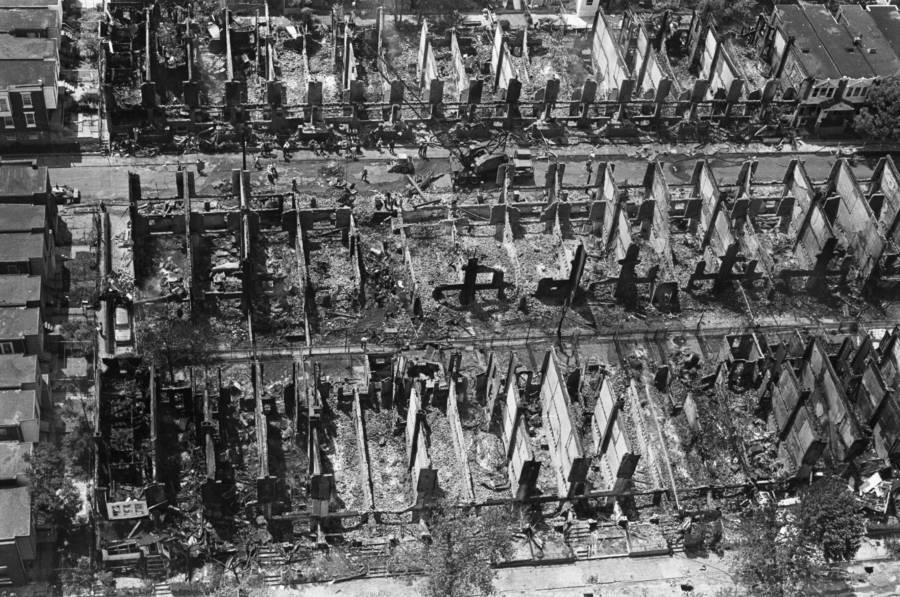

Bettmann/Getty Images250 Philadelphians were left homeless after the MOVE bombing razed 61 homes to the ground.

The neighbors practically begged Wilson Goode, Philadelphia’s first Black mayor, to resolve the issue. Sadly, his 1985 order to evict MOVE would not only mirror the problems of 1978 but result in far greater tragedy — and more than 10 times the body count.

The mandatory evacuation began on May 12th but spanned into the following day when MOVE members refused to budge. That night, the Philadelphia Police Department took drastic measures and bombed an American neighborhood.

The C4 and Tovex-infused satchel bomb that police detonated on the MOVE house’s roof ignited a fire so enormous that it razed 61 homes to the ground. Five children and six adults were killed in the attack, including John Africa — whose mangled body wouldn’t be identified for months.

The only two survivors — Birdie and Ramona Africa — escaped with horrible burns. Two grand jury investigations followed, a civil suit, and a commission report that described the bombing as “reckless, ill-conceived, and hastily-approved.”

Africa’s Complex Legacy As A Martyr

John Africa’s legacy is difficult and contradictory. Whatever progressivism he espoused, it’s hard to ignore that he ordered MOVE’s child members to abandon their parents if they weren’t following his tenets and supported physical punishment. In July 1984, his sister Louise James told police that her brother was legally insane.

He preached environmental balance and an end to reactionary violence but stockpiled such an arsenal that an altercation appeared inevitable. Nonetheless, the 1985 bombing was an unforgivable act of state-sanctioned murder that turned John Africa into a martyr, regardless of his flaws.

HBOA still from HBO’s 40 Years A Prisoner documentary.

Recently chronicled in HBO’s 40 Years A Prisoner documentary, MOVE is alive and well today. John Africa’s concerns seem prescient in an era where police are increasingly militarized and move counter to a protesting citizenry who are, for the most part, unarmed.

As for Glassey, the original MOVE member? He has no regrets — and felt it necessary to put an end to Africa’s iron grip.

While an unscrupulous leader with cult-like strategies and a ruthless readiness for violence, the core philosophies of MOVE nonetheless remain as contemporary as ever.

“I’m fighting for air that you’ve got to breathe,” Africa said in court in 1981. “And I’m fighting for water that you’ve got to drink, and if it gets any worse, you’re not going to be drinking that water. I’m fighting for food that you’ve got to eat. And, you know, you’ve got to eat it and if it gets any worse, you’re not going to be eating that food.”

After learning about MOVE founder John Africa, read about the incredible 19th-century Black activist Ida B. Wells. Then, learn how Black undercover cop Ron Stallworth joined the KKK.